THE SKY WAS VERY CROWDED THAT MORNING:

TWO CANADIAN AIRMEN STIR UP A GERMAN HORNET’S NEST, WHICH IN TURN STIRS UP AN ITALIAN ONE

By Jon Guttman

(from Volume 22 Issue 11, December 2015)

Captain William G. Barker strikes a somewhat sheepish pose after crashlanding his Sopwith Camel B6313 'N' of No. 28 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, near Grossa aerodrome in Italy. B6313 was soon repaired and flying again, with Barker scoring 43 of his 50 victories flying it. (LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA, 3623376)

December 26, the traditional day after Christmas, is also celebrated in Italy as St. Stephen’s Day, and throughout the British Commonwealth as Boxing Day, a day for banks to close and for employers to give boxed presents to their employees. On December 26, 1917, however, the wartime skies over northern Italy were open for business as German aircraft staged two bombing attacks on Istrana aerodrome, about two miles from the town of Trevignano.

What followed was one of the largest air battles to be fought over the Italian front. What started it, however, was an incident that had nothing to do with either of the principal combatants.

In response to the crisis caused by the Italian rout at Caporetto on October 24, 1917, Britain and France both sent army and aviation contingents to bolster the Italian forces. The British contribution included the VII Brigade, Royal Flying Corps (RFC), consisting of the 14th and 51st Wings, encompassing Nos. 34 and 42 Squadrons, equipped with R.E.8 reconnaissance planes, and Nos. 28, 45 and 66 squadrons, with Sopwith Camels.

Reaching Milan on 12 November, 28 Squadron settled in at Grossa on the 28th, and flew its first mission escorting 34 Squadron’s R.E.8s the next day. In the course of that sortie, the British got into a 20-minute fight with 12 Albatros fighters and ‘C’ Flight’s Canadian commander, Captain William George Barker from Dauphin, Manitoba, fired 50 rounds at one, which went into a vertical dive. “I followed as he flattened out at 5,000 feet,” Barker reported, “I got a burst of about 80 rounds at close range. His right wing folded back to the fuselage and later the lower wing came off.” Barker’s fourth confirmed victory was Leutnant in der Reserve Edwin Haertl of Jagdstaffel 1, one of the three German fighter squadrons stationed in Italy, who crash landed near Treviso.

After completing an R.E.8 escort mission on December 3, Barker led Lieutenants Arthur G. Cooper and Stanton Waltho over the Piave River and attacked a kite balloon northeast of Conegliano. Barker’s 40 rounds had no effect, but looking up he spotted an Albatros preparing to attack Waltho. He intervened and shot the Albatros down in flames. Barker then returned to the balloon, which was rapidly being pulled down, and closing to point-blank range, managed to set it on fire. He strafed the winch crew for good measure, as well as an enemy staff car, which ran into a ditch. Barker’s Albatros had again been German and this time the pilot, Lieutenant Franz von Kerssenbrock of Jasta 39, was killed, as was the Austrian balloon observer, Lieutenant M. Riegert of Ballon Kompagnie 10.

The Germans were now painfully aware that there were Camels operating over the Piave, although the British had little or no intelligence on which of their opponents were German and which represented the predominant Austro-Hungarian Luftfahrtruppen. Over the next few weeks, though, Barker decided that the enemy was not making enough of an appearance. Therefore on Christmas Day, he led Lieutenant Harold Byron Hudson to Motta di Livensa aerodrome, 10 miles in enemy territory, where the two Camel merchants dropped a large piece of cardboard inscribed: “To the Austrian Flying Corps from the English RFC, wishing you a very Merry Christmas.” They then shot up the airfield, setting fire to a hangar and damaging four aircraft.

Barker’s and Hudson’s holiday greetings may have been meant for the Austro-Hungarians, but the recipient was Flieger Abteilung (Artillerie) 204, and its German personnel were not amused. If the Canadians wished to stir up trouble, they succeeded. One day later — Boxing Day — the Germans launched a bombing raid on Istrana airfield. As far as retaliation against 28 or any of the Camel squadrons was concerned, however, the Germans, too, had pinpointed the wrong target — Istrana’s occupants were all Italian. And they had been just itching for the opportunity to try out some new Hanriot HD.1 fighters they had recently acquired from France.

Lacking a suitable indigenous fighter design when it entered the war in May 1915, Italy had mostly used French-designed Nieuports, largely built under license by Giulio Macchi. In the autumn of 1916, however, Capitano Ermanno Beltramo, a member of the Italian Military Aviation Mission in Paris, contacted René Hanriot, and his chief engineer, Emile Eugène Dupont, requesting a fighter to replace the Nieuport. By November, Dupont had created a compact single-seater powered by a 120-hp Rhône 9J rotary engine, the HD.1. Structurally conventional with a wooden, fabric-covered structure, the HD.1 was well-proportioned and aesthetically pleasing. More important, Italian test flights in February 1917 earned it praise for speed, visibility and ease of handling that were all superior to the Nieuport 17s. Italy ended up purchasing a total of 360 HD.1s from Hanriot, and of the 1,700 it ordered from Macchi, 831 would be delivered by the end of the war, with another 70 completed by February 1919.

A Hanriot HD.1 of the 76a Squadriglia flown by Tenente Mario Fucini in January 1918. Fucini claimed 11 victories during the war, of which seven were confirmed. (ROBERTO GENTILLI)

The first HD.1s reached the 76a Squadriglia at Borngano in July 1917, but by October 26 only the 78a Squadriglia had likewise converted — just as the Austro-Hungarians, with German assistance, were achieving their breakthrough at Caporetto. In consequence, both squadrons had to destroy 16 of their new fighters and retreat to Istrana. At that point, Macchi was producing its own HD.1s, which it delivered to the 82a Squadriglia in early November, soon followed by the 70a, 80a and 72a. The first HD.1 victory was claimed by Sergente Alessandro Contardini of the 82a on 6 November, and the first loss was Aspirante Vittorio Aquilino of the 78a, shot down near Maser on the 14th — possibly the unconfirmed Sopwith claimed over Il Montello by Leutnant in der Reserve Bussmann of Jasta 1.

Winter in the foothills of the Italian Alps was not the best of times for wartime activity, and for the most part, both sides were preparing for major operations in the coming spring — until Barker and Hudson spurred the Germans to mount their reprisal raid on 26 December. At 0900 hours, reports from frontline troops of at least 30 German aircraft on the way sent at least 16 Hanriots of the 70a, 76a, 78a and 82a Squadriglie scrambling up just as the raiders reached Istrana.

Often mistaken for a Camel, this Hanriot HD.1 of the 82a Squadriglia carries the resemblance further by using letters for individual identification, much like the Royal Flying Corps. (ROBERTO GENTILLI)

Attacking in an untidy formation at altitudes between 500 and 3,000 feet, the Germans, all two-seaters without escort from any of their three Jagdstaffeln, dropped one bomb on a hangar of the 76a

Squadriglia, wrecking or damaging a few HD.1s, killing six ground personnel and injuring some others. Then it was the Italians’ turn.

After takeoff Sottotenente Silvio Scaroni of the 76a had barely completed a circuit of his field when he saw three DFWs boring in at 500 feet to scatter their bombs around the hangars. “I attacked the closer one, which was engaged in strafing the airplanes of my squadron lining the field,” he wrote his family. “With two short, well-aimed bursts I brought it down just at the border of the airfield. It crashed and caught fire.

Captain James H. Mitchell of No. 28 Squadron scored six of his 11 victories flying Camel B6344, including the AEG shared with two Italian pilots on December 26, 1917. (AARON WEAVER/LES ROGERS)

“Then another large aircraft passed above me two or three hundred meters higher. I gave full throttle and I quickly got at it. Keeping a bit lower and behind to remain hidden, I started firing, aiming more or less at the cockpit section. At my first rounds the pilot tried to maneuver and get free of my attack so that the observer could use his machine gun against me, but he couldn’t do it so he went in a dive and I was above him. Then another Hanriot came next to mine, and from the insignia I saw it was [Sottotenente Giorgio] Michetti. The enemy was trying to regain his lines but it was a long trip and we were determined to not let him go. Michetti and I yo-yoed attacking him with short bursts. The observer, thanks to the excellent maneuvering of the pilot, fought us back with admirable ability and tenacity, making our attacks difficult and ineffective. We had harassed him down to 50 meters above the ground and its maneuvers were getting slower and more difficult, while we were sure of victory and got more and more aggressive. The observer stopped firing and I understood why: I saw him quickly removing a new cartridge belt tied around his waist to replace the empty belt in his gun. I exploited that moment and from close range I fired one last burst. This time the pilot went down, hoping to escape with a good landing, but when it touched the ground the airplane turned over. Now we saw it, all white, with its huge crosses, defeated. As we flew around it we saw the passenger crouching and getting out, then with a special explosive device he torched the wreck without worrying about the pilot who died miserably in the fire. The explosion of the fuel tanks also splashed burning fuel on the passenger, who started thrashing and rolling on the ground. Some artillery men reached him and helped him by removing his burning clothes, then they captured him.”

Leutnant in der Reserve Johann Edelbohle of Flieger Abteilung 2 had been the unfortunate pilot, while his observer, Leutnant Pallasch, was taken prisoner.

Sottotenenti Giogio Michetti and Silvio Scaroni pose beside a camouflaged HD.1 with Scaroni's white square personal marking. The two frequent wingmen teamed up to bring down a particularly feisty DFW C.V over Istrana and both survived the war. Michetti had five victories while Scaroni was Italy's second ranking ace with 26. (ROBERTO GENTILLI)

In his combat report, Sergente Andrea Theobaldi, one of six 82a Squadriglia pilots involved in the fight, wrote: “I took off at 9:15 under a hail of bullets, when I reached a ceiling of 600 metres, I found myself in the middle of a group of enemy fighters flying in the direction of our airfield … I tried to attack them, but I soon realized that they were encircling me … An enemy machine detached itself from the group and I flew straight after it and, with just two quick bursts, I saw it go down and land in a field northeast of Camalò. The enemy aircraft turned over and started to burn … I could see one of the airmen crawl out of the airplane as quickly as he could … his legs were on fire …”

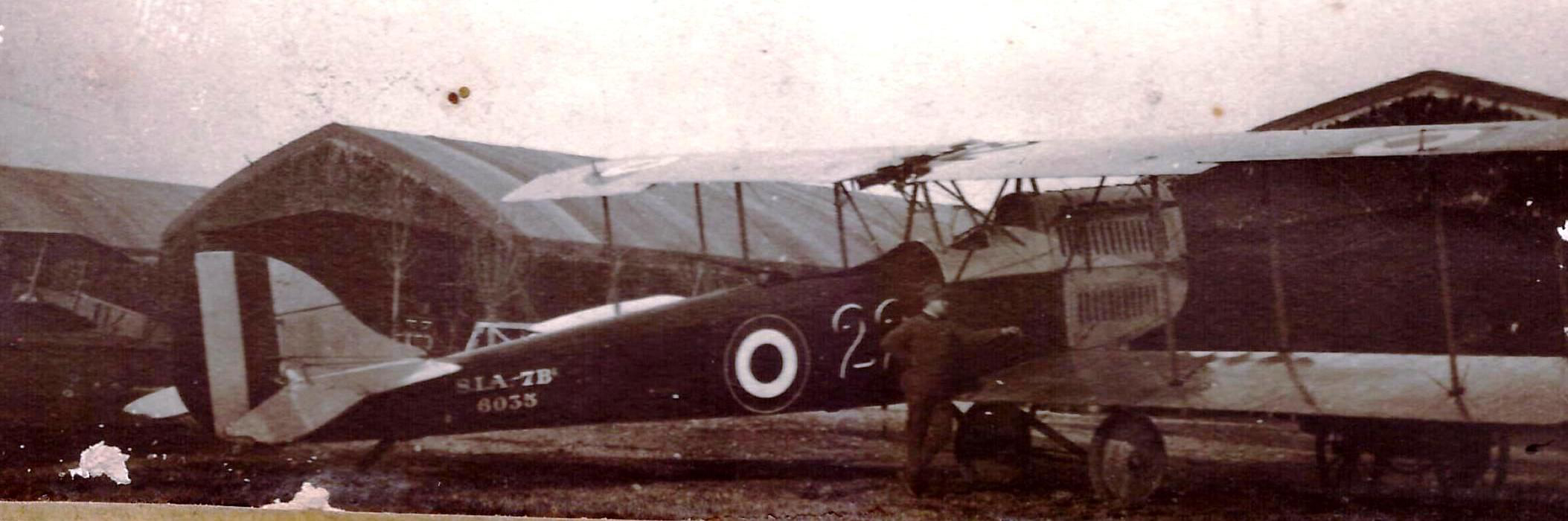

A little-known postscript to the Istrana raid is that an SIA 7B, newly delivered to the 22a Squadriglia, was piloted by Sergente Alfio Lepore with Soldato Ercole Biemmi, a worker and rigger for the SIA company attached to the unit who was in the observer's pit, gave belated, vain chase to the retiring Germans. (ROBERTO GENTILLI)

Theobadi had only fired 45 rounds when he landed at 0955. His first victory was one of two DFWs whose crews were taken prisoner in the vicinity: Unteroffizier Hedessinski and Leutnant Kessler of Flieger Abteilung 2, taken at Trevignano, and Vizefeldwebel Pohlmann and Leutnant Schlamm of Flieger Abteilung (A) 219, captured at Povegliano.

At 1230, a second wave of Germans came in, this time including the first AEG G.IV twin engine bombers to appear over Italy, courtesy of Kampfstaffel 19, Kampfgeschwader 4. Two more DFWs and one of the AEGs was shot down this time, the latter having run a gauntlet of HD.1s and Camels that resulted in it being credited to Captain James H. Mitchell of No. 28 Squadron, Sottotenente Scaroni of the 76a and Sergente Giacomo Brenta of the 78a Squadriglia.

“My machine’s gun sight, dimmed by the change of temperature after a steep dive of 7,000 feet, did not allow me to take perfect aim,” Scaroni wrote in his autobiography, Battaglie

Nel Cielo. “Nonetheless, I shot at it at random, hoping for the best, but naturally I missed it.

“While I was preparing for a new attack, the huge machine was destroyed by the precise shots of my Italian colleague. I set off for my airfield, as the work is now over. Flying beside the other Hanriot, I realize with joy that it is flown by my friend Brenta.”

In a letter to aviation historian Rinaldo d’Ami decades later, General

Brenta recalled: “I can simply tell you that I was able to draw closer to it, but nobody else was near me, except Scaroni, who was coming on very fast. I fired some 50 rounds and I presume I hit the pilot, as the huge twin-engine machine immediately went down in a vertical dive … However, if a British officer made a claim on the enemy aircraft, then he must have attacked it before I did … The sky was very crowded that morning.”

Killed in the AEG were the pilot, Unteroffizier Franz Hertling, and his crewmen, Leutnant

Georg Ernst and Leutnant in der Reserve Otto Niess. The Germans claimed three enemy fighters in the course of the raids, but in fact neither the Italians nor the British had lost anything. On the other hand, the Italians and No. 28 Squadron claimed eight DFWs as well as the AEG.

Scaroni and Michetti met the observer they had brought down that morning, who vehemently insisted that it was British Camel pilots who had brought him down. Mistaking the aircraft types was understandable, since there were some Camels involved and the Hanriot was an unfamiliar debutante whose rotary engine and general configuration bore a resemblance to the well-known British fighter. Scaroni and Michetti, however, also attributed their captive’s attitude to Prussian arrogance, unable to accept being bested by Italians. The stereotyping was mutual, however, for upon learning that all of the downed raiders were German, Scaroni remarked, “This explained their aggressiveness and their daring” — reflecting a lower opinion of the Austro-Hungarians.

Although the air battle had ended in a morale-raising victory for the Italian airmen, it also alerted them to the danger of concentrating so many squadrons on a single airfield. Therefore they immediately transferred the 70a and 82a Squadriglie to San Pietro in Gu.