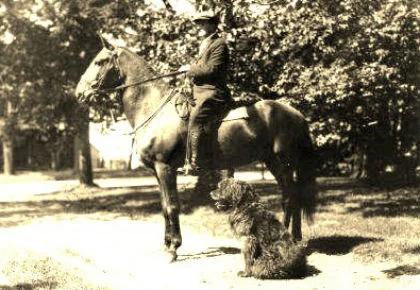

LCol Bent (left) mounted on Fritz, at Engelskirchen, Germany during the form-up parade as the Battalion prepared to leave Germany, 7 Jan 1919. On the right is Major John Girvan DSO, MC and Bar, CDG, who commanded at The Crow's Nest. (15th Battalion Memorial Project)

The Crow's Nest

It was little more than an isolated skirmish, but it exemplified the tactical stalemate of trench warfare during WWI

By Bob Gordon

Fifteen kilometres southeast of Arras a slight, but sharp rise in elevation dominates the village of Hendecourt-les-Cagnicourt, 700 metres to the south. Known to the Canadians during World War I as the Crow’s Nest, it might pass unnoticed in many parts of the world. However, in the flat, relatively featureless terrain of Canton de Vitry-en-Artois, it offers a considerable field of view, hence the name. The 48th Highlanders’ regimental history captures the physical and psychological dominance of the Crow’s Nest, noting it as “A high hill, squatting, content in its security … a landmark for miles and the dominating position in the sector.”

In the final days of August 1918, the Germans constructed a strongpoint surrounding this promontory. It included many machine guns with superb fields of fire, and offered an excellent lookout for artillery officers observing the fall of shot. Only a kilometre west of the Drocourt-Quéant Line (D-Q Line), it overlooked the areas that a Canadian attack would require as jumping off points.

On August 31, the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders) was ordered to capture the Crow’s Nest and, a few hundred metres to the south, Château Hendecourt and Château Wood the following day. Proximity to the D-Q Line meant that the Crow’s Nest could not be bypassed, surrounded and forced into submission; it had to be taken head on and quickly. The capture of these objectives would set the stage for the attack on the D-Q Line on September 2. It was the overture to the symphony of violence that was to follow.

It is important to note that, at this time, almost one month into the Hundred Days, the Canadian Corps was fighting a war of movement on a fluid battlefield. It was mobile, industrial warfare never seen before: fire and movement tactics based on specialists operating in concert reaching maturity. Knowledge of the strength of the German garrison, details of the trench system and other information — despite aerial photography — was not as thorough as during the static phase of the war. However, the tactics and technology of the attack had also advanced since 1915. This small unit action reveals the Canadian Corps in its prime, fighting as the ‘shock troops’ of the British Empire.

Orders for the attack came from 3rd Brigade HQ at a battalion commanding officers’ conference held at 1400 hrs on August 31. The plan called for the 15th Battalion to make a straightforward, frontal assault on two objectives. No. 2 and 4 Companies (trench strength 139 and 135, respectively) were to spearhead the assault. The former was detailed to capture the Crow’s Nest, the latter the château and surrounding woods. The positions were to be overrun after a hurricane bombardment and then reinforced pending the inevitable German counterattacks.

This is a detail of the map on which the attack would have been planned. Hendecourt is in the lower middle. Successively, moving northeast, the Chateau and the Crow's Nest are labeled. Overlays identify troop concentration areas, jump off lines and objectives. (15th Battalion Memorial Project)

The bombardment was to roll across the objectives with 100-yard lifts every four minutes. The 4.5-inch howitzers were detailed to preselected targets. No.1 (trench strength, 138) and No. 3 (trench strength, 126) companies were in reserve and support, respectively. The 14th Battalion would attack in support to the north and the 2/7th King’s (Liverpool) Regiment was to attack Hendecourt village on the right flank. The garrulous CO of the 16th Battalion, LCol ‘Cy’ Peck, offered his support as the conference closed: “If you need the 16th, John, you can have the whole damned battalion.” It almost came to that.

The assault was under the overall command of Major J.P. Girvan, MC. The second in command was Capt. W. Maybin, MM and the intelligence officer and HQ signaller was Lt. G.M. Malone. The assault companies, Nos. 2 and 4, were under the command of Captains A. Samuel and G.S. Winnifrith. No. 3 Company (support) was commanded by Lt. T.M. Cowan while No. 1 Company, under command of Capt. H.P. Edge, was in reserve.

Interestingly, a battalion tumpline officer, Lt. R.Y. Inglis, was responsible for seeing that the ammunition reached the troops on the objectives. The tumpline was a Canadian innovation derived from the experience and equipment of packers in the northwest that involved the weight of the load being carried on a strap that ran over the shoulders and across the forehead. It allowed a man to increase his load by 50 to 100 per cent.

On the evening of August 31, the assault companies were deployed in Ulster Trench on both sides of the Cherisy-Hendecourt Road — approximately one kilometre northwest of Hendecourt. No. 2 Company was sheltered in the 500 metres of trench north of the road, while No. 4 filled the corresponding section of trench on the south. They were slated to relieve the 1st Brigade in the front line commencing at 0100 hrs and go over the bags at 0450.

No. 2 moved forward to the section of Cemetery Avenue due west of the Crow’s Nest and south of Unicorn Avenue. No. 4 moved into Cemetery Avenue in the section where it crosses the Cherisy-Hendicourt Road adjacent to the eponymous graveyard. The reserve and support companies were located in Unicorn Avenue, due north of Hendecourt 800 metres. All companies were in position by 0330.

Only hours before the attack, an Alsatian prisoner confirmed that the Germans remained unaware of the impending attack. That said, the German counter barrage, rehearsed and registered on the afternoon of August 31, was to prove deadly to the support troops when it commenced three minutes after Zero Hour.

“The plan was as successful as it was simple. ”

Chateau Hendecourt , located in Chateau Wood, was the objective of NO. 4 Company on September 1, 1918. It was also here that Fritz entered regimental history when his rider and accompanying orderly mistakenly rode into the clutches of the regiment. (15th Battalion Memorial Project)

A short, sharp barrage burst as the men went over the top at Zero Hour. The battalion’s after action report offers a concise description of the tactical plan: “It was decided to overrun the enemy positions as quick as possible.” A line of skirmishers advanced 55 metres in front of the main body of two platoons, advancing in line. Two platoons of No. 3 Company followed each of the attacking companies, advancing sections in file.

The plan was as successful as it was simple. The Crow’s Nest was revealed to be bristling with machine gun bunkers and nests. Most of these were overrun before their gunners could bring them into action. The battalion’s after action report later noted: “the ground captured was littered with Machine Guns & Trench Mortars but as there was so much more important work to be done there was no attempt made to collect or count our booty.”

By 0600 a visual signalling station was operating on the western side of the Crow’s Nest. The first messages began arriving shortly after, and they were universally positive: “Crow’s Nest taken. 50 prisoners, 1 officer. Casualties light.” And minutes later, at 0613: “Advance going well on left. Some prisoners going back. Now sniping from Chateau Wood. Imperials held up on right.” Within 90 minutes, the Crow’s Nest was secured.

The assault on Château Wood went well, but not with the rapidity of the assault on the Crow’s Nest. (The result was the sniping reported above.) The principle difficulty was in Hendecourt village. The British troops were held up and No. 4 Company had its left flank in the air. A platoon of the reserve company was dispatched immediately, followed by a second, to form a shoulder protecting the No.4 from enfilade fire. No. 9 and No. 11 platoons of the support company were established on the Crow’s Nest as a main line of defence and the final two platoons of the reserve company took up their positions behind the Crow’s Nest. Meanwhile, the assault platoons extended their outposts up to 350 metres forward of the objectives.

Vickers machine guns of the 3rd Company, 1st Division Machine Gun Battalion, accompanied the assault but were not employed. Their purpose was to support the defence of the objective not to assist in its capture. They were simply more baggage throughout the initial advance. However, once the objectives were seized, they were sighted to protect them with clear, interlocking fields of fire.

The forward slope of the Crow's Nest, "a landmark for miles and the dominating position in the sector” along the line of advance for No. 2 Company. The final few hundred yards were devoid of cover while the elevated Crow's Nest itself was partially forested and defended by dug in machine guns and mortars. (15th Battalion Memorial Project)

Throughout the morning, runners arrived at battalion advanced HQ, with information confirming a short, sharp battle crowned with success. At 0845 No.4 Company sent a written report, confirming an earlier verbal report “that this Coy is on its objective now.” The note also stated that they were having trouble establishing contact with No. 2 Company north of Trigger Alley and requested “M.G.'s cover sunken road running east from village [Hendecourt], also Trigger Alley & valley between this Coy & 2 Coy.” The message also requested 100 Lewis magazines and “about 200 Mills [bombs] in event of attempt to bomb down Trigger Alley.”

No. 2 Company faced a threat from its direct front also. Hans Trench had previously supplied the Crow’s Nest and ran forward from the D-Q Line, terminating on the Crow’s Nest’s east side (in its lee, from the German perspective). Now it was a pipeline into the heart of No. 2 Company’s position. Overall, however, acting OC ‘Dusty’ D’Esterre’s messages have a downright jaunty turn throughout the morning. D’Esterre reports calmly that he has contact with No. 4 on his left, and is “consolidating in shell holes very fast … Capt. Samuel got a nice Blighty,” and dashingly includes the postscript, “Ferg wants a bottle of Scotch.” At 1105 he gleefully reports that Private Marshal has downed a German double-seater with his machine gun only 300 yards from the headquarters. (Even more reason for a bottle of scotch!)

With their machine guns deployed and outposts established, the Highlanders dug in as they waited for the inevitable counterattacks. Twice in the late afternoon, the Germans concentrated to counterattack. On both occasions artillery broke them up before they reached the Canadian lines. With night falling, the Canadians tenuously held both objectives. Consequently, Capt. Maybin asked that the “16th stand ready” to reinforce him. However, by 1955 hrs, Maybin reported “situation now clearing.”

The last German casualties of the day were an officer and his valet/groomsman. Returning from extended leave, the officer believed Château Hendecourt remained in German hands and, more specifically, was still his HQ. He boldly rode into the hands of No. 4 Company and his horse, renamed Fritz by the 15th Battalion’s CO, galloped into regimental lore as a much-loved mascot.

Author’s note: A special thank you to BGen (ret’d) Greg Young for generously sharing his time, knowledge and resources.

Fritz: The War “Trophy” Horse

LCol Bent, at home on his fruit farm near Paradise, Nova Scotia, with the two loyal friends he brought back from the fighting in Europe. His horse Fritz, who originated in Russia and was captured by the Germans and sent to the Western Front, was eventually captured by the Canadians and became the Colonel’s personal mount. In the foreground is Bruno, the Belgian Sheepdog Bent adopted as a puppy. (15th Battalion Memorial Project)

When Fritz, “a splendid dark bay” was buried alongside Bruno, a Belgian Sheepdog, he had travelled the world and seen more of the war than most men. Fritz and Bruno were the mascots of the 15th Battalion. Both returned home with the commanding officer, LCol “Charlie” Bent, DSO, and lived out their lives on his fruit farm in Paradise, Nova Scotia.

Bruno was a stray Belgian Sheepdog that was adopted by the unit as a puppy in August 1915. Fritz, on the other hand, was a true “warhorse”: booty taken from the enemy on the field of battle, a living, breathing, battlefield trophy.

There is good reason to believe that Fritz originated from the Russian steppes. He likely began his service as an officer's mount with the tsar's army before being captured by German forces and then, at some point, transferred to the Western Front. It was there that he was captured by the Canadian 15th Battalion. As a result, Fritz served on both Eastern and Western Fronts and for three different armies — Canadian, German and Russian.

The story of how Fritz was captured at Château Hendecourt by No. 4 Company during the Crow's Nest operation is one of chance. A German officer and his orderly were returning from a period of leave late in the evening of September 1, 1918. On their departure, Château Hendecourt had been their headquarters; they had no idea that earlier that very day the Canadians had occupied it. Returning to what they thought was their unit headquarters, they blithely rode across Allied lines. The two were quickly dispatched as prisoners of war to be interrogated. The horse, of no intelligence value, remained with the battalion and became LCol Bent's mount.

Fritz survived the war. Photographs place him at Engelskirchen with the regiment in 1919. He arrived in Canada with the regimental mounts and probably travelled to Bent’s farm via rail. There, in Paradise, the three long-serving veterans of WWI lived out their final years. Tragically, when Fritz became too frail to carry on, and with no veterinarian available, Bent had to put him down personally.