By Chris Chlon

Camp 30, the POW camp in Bowmanville, Ontario for German soldiers.

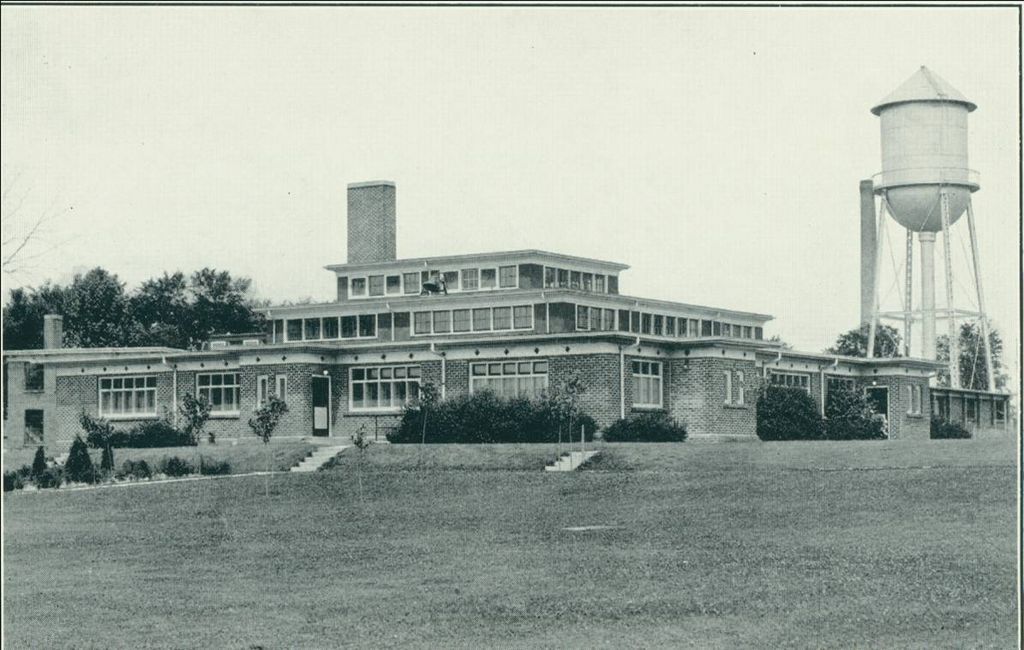

Bowmanville, Ontario, sits in Southern Ontario about 75 km east of Toronto and 15 km east of Oshawa on Highway 2. The town was a stand-alone incorporated community from 1858 to 1973. In 1941, there was a school for “unadjusted boys who were not inherently” delinquent in the town on the former farm land of Mr. John H. H. Jury. He donated his land to the government for the school in 1927 which was constructed soon after. It was in use until April 1941 when the government gave the school notice to find a new home because the facility was going to be turned into a prisoner of war camp. Seven months later, the school located at 2020 Lambs Road changed dramatically with the installation of barbed wire fences, guard towers, gates and barracks for the guards. Work was completed in October 1941, and the POW’s began to arrive there, and it was designated as Camp 30.

Compared to other POW Camps, this one had lots of things that others lacked such as an indoor pool and athletic complex, soccer and football fields. The prisoners played sports there including soccer, Canadian football, and hockey in the winter. The prisoners, themselves, built a tennis court and a mini zoo. They were allowed to receive and send mail from family. They received new uniforms from Germany, and got their regular pay with which they could buy such items as cigarettes, cigars, tobacco, pipes, matches, writing tables, pens, pencils, ink, razor blades, etc. Medical and dental services were provided by German doctors. An orchestra and theatre group put on various Shakespeare plays.

Since the camp was located on a former farm, the prisoners’ meals were much better than those served in other camps. Breakfasts consisted of coffee, jam, and butter. Lunch often featured roast beef, gravy potatoes, and carrots. For dinner macaroni, ham, soup, cheese bacon and tea were on the menu.

Even though the living conditions at the camp were quite good, it was still a prison camp, one that held high ranking officers of the Afrika Korps, Luftwaffe, and the Kriegsmarine. One of the prisoners was the all-time ace of the U-Boat fleet, Fregattenkapitan Otto Kretschmer. Beginning in October 1939 and continuing to his capture in March 1941, Kretschmer sank 208,954 gross tons of allied shipping. For his efforts, he was given several decorations with the highest being the Knights Cross, and the Knights Cross with Oak Leaves. He was so successful that he was given the nickname, Atlantic Wolf. His reign of terror against Allied shipping came to an end on March 17 1941, when his U-boat, U-99, was sunk south-east of Iceland. He ended up at Camp 30 with others from his crew. However, in October 1942, he decided that he had had enough of being a POW, and he decided to escape.

He developed a plan with three other U-boat officers, Kapitanleutnant Hans Ey of U-433, Horst Elfe of U-93, and Joachim von Knebel-Doberit to escape. Before proceeding though, Kretschmer needed to contact U-Boat Commander, Karl Donitz, for permission. This was accomplished by sending a coded letter to the spouse of Knebel-Doberitz who happened to be the secretary of Karl Donitz. In the letter, he relates his intentions to escape, and proposes that the escapees be picked up by a U-boat, and he even proposed a location for that. Donitz approved the escape attempt, and shortly afterwards, preparations began.

Kretschmer intended to burrow under the camp in a tunnel. To throw off camp guards, three tunnels were created. Over 150 prisoners took part in the digging. The intended escape route would extend beyond the camp and the barbed wire that surrounded it. At the same time, others prepared false identification papers, civilian clothes, and dummies to be used as substitutes for the escapees.

While the work was being carried, coded letters with progress reports and updates were sent to Germany. In August 1943, through a coded letter and radio transmission, the date was set for the break out. In yet another letter from Donitz, Kretschmer was advised that the U-536 U-boat, commanded by Lieutenant Schauenberg, would surface every night for two weeks beginning on September 23, 1943. Kretschmer and his men would have 14 days after their escape to make it to the rendezvous location at Pointe Maissonette in Chaleur Bay.

What the Germans did not know was that the escape plans had been discovered by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police who with the Canadian Military Intelligence. Maps of Eastern Canada made their way to the POW’s and one was for a rescue operation in Chaleur Bay. To do this, the RCMP by use of a microphone discovered the presence of a tunnel and the sounds of digging. However, this information was not shared with the prisoners. The intent was to allow the Germans to keep digging and apprehend them once they emerged from the tunnel.

Two incidents changed the German’s efforts, code named Operation KIEBITZ. Digging the tunnel meant having to hide the dirt, and this was accomplished by putting it above the ceiling in the building where they were housed. One week before the attempted escape, the ceiling caved in causing a racket which alerted the guards who began to search for the source of the dirt. Due to this unexpected problem, Kretchmer decided to take action that night. However, another surprise occurred when a prisoner digging close to the camp’s fence in order to fill his flower boxes with dirt, the ground beneath him caved in, and uncovered the third tunnel to the guards. The escapees were arrested and put under close watch for the efforts.

One German officer, Kapitanleutnant Wolfgang, Heyda, devised his own personal escape plan and presented it to Kretchmer. After listening to Heyda’s idea, Kretschmer agreed and allowed Heyda to proceed. He was provided false national registration papers along with a false document signed by Canadian Naval Chief-of-Staff, Admiral Percy. He was given civilian clothing, a boatswain’s chair-a-rope chair that can be attached to cables, and nails were pounded into his shoes to make crampons.

Heyda, using a dummy, evaded the evening prisoner count, hid a hut. A diversion created by other prisoners allowed him to sneak out of the hut and scale a fence pole helped by the nail crampons in his shoes. At the top of the fence, he gets into his boatswain’s chair and attaches himself to the ropes and vaults over the fence to freedom. He made his way overland to Bathurst, New Brunswick on September 26, 1943, the date the submarine was to begin surfacing for two hours a night for two weeks. On foot he reached the rendezvous point of Pointe Maisonette. He was arrested in front of the lighthouse the night of the arranged U-boat rescue, and returned to Camp 30.

Operation Pointe Maisonette was the code name of the Canadian counter-operation to the Germans. The counter-offensive, a task force, was led by HMCS Rimouski (k121) which had been equipped with an experimental edition of diffuse lighting camouflage specifically for this operation. Other ships involved were a destroyer, HMCS Chelsea, three corvettes: HMCS Agassiz, HMCS Shawinigan, and HMCS Lethbridge, five minesweeping boats and fairmiles. The camouflage used light projectors to make a ship nearly invisible to enemy vessels after dark. It rendered the ship indictable from a distance, difficult to see and identify when closer. Lieutenant Pickford commanded the HMCS Rimouski and described its role in this operation: “They had installed a radar station and observation posts on the beach, and when they received an indication of the presence of a U-Boat, HMCS Rimouski with her luminous camouflage was to abandon the patrol and enter the bay on her own. Sailing slowly with her navigation lights and her luminous camouflage, she would create illusion of being a small ship until she was able to capture the submarine.”

Preparations on land to foil the escape comprised a combined operation by Royal Canadian Engineers, the Royal Canadian Army, and the Army service corp. Their task was to install two mobile radar posts on either side of the Point Maisonette lighthouse. Desmond Piers, a retired Rear Admiral, was a lieutenant at the time. He described how he learned of the secret mission: “One day, I was called into a room where there were three men, amongst them Admiral Puxley and Capitan Hill, Captain of the Canadian submarines. What we were about to here was secret and it had to stay that way, even from our spouses. Admiral Puxley began telling us how German prisoners at Camp Bowmanville, Ontario, had prepared their escape. Kretchmer, a U-boat captain and other submariners were planning on making their way to Chaleur Bay to be picked up by a submarine.”

One battalion of Royal Canadian Engineers, Captain Lafond commanding, transported the mobile radar posts. Captain Lafond explained his role: “I had to organize a convoy of two radars, their generators, the staff required for their operation, about forty soldiers of the R.C.A, a section of combat engineers, as well as 24 drivers from the Army Service Corps?...Why all of that? I’m not sure if I found out right away, or upon my arrival at Bathurst, from the Captain, who was waiting for us. In any event, the objective of this hasty move was to seize a German submarine in Caraquet Bay, north of Bathurst.”

The naval task force waiting in Caraquet Harbor, obscured by Caraquet Island, on the night of September 26-27, 1943. It detected the presence of U-536 off Pointe Maisonette while the lone escapee, Heyda, was arrested on shore.

On August 29, 1943, U-536 with KapitanleutnantRolf Schauenburg’s in command departed the German sub base a Lorient, France, and eventually arrived at the mouth of the Gulf of the St. Lawrence on September 16, 1943. Schauenburg’s orders were to establish contact with the prisoners and wait for their signals from September 26 for two weeks.

The prisoners had light signals which were to be used to indicate the rendezvous site. After the submarine was close to the shore, a German officer would be landed along with an assistant, and a boat to recover the prisoners.

On the night of September 27, U-536 surfaced to wait on a signal from the prisoners. It never came because while the returned escapee, Heyda, was being interrogated, the Canadian radar operator received a contact warning of the U-boats arrival close to shore. Lieutenant Piers sent a message to the ships in the bay, informing them of the presence of the submarine. The gist of the message was: “Finally they received the message. It was a radar contact. The plan was as follows: the corvette HMCS Rimouski would enter the bay on her own with her luminous camouflage that rendered her less visible. The navigation lights were out, as would have been those of a Merchant Ship under similar circumstances. We were to sneak up on the submarine, and, if possible, capture here. Therefore, we proceeded into the bay lit up like a Christmas tree.”

Two attempts to contact the submarine by an English officer who spoke German, and a radio message did not succeed. Schauenburg, by now suspicious, moves the sub further from shore and submerges in 30 meters of water. The flotilla of ships began hunting their prey by launching depth charges, but the submarine incurred only minor damage, and made its way out of the bay, but in doing so became entangled in the nets of a fishing trawler. Members of the submarine’s crew removed the nets. Later the submarine surfaced but was spotted by three destroyers and a fishing vessel. It immediately dived and headed for shallow waters along the coast where it was attacked but managed to escape to Cabot Strait. The escape took a long time and members of the crew lost consciousness and were poisoned by breathing foul, polluted air in the U-boat. It eluded its attackers headed to Portugal. While on its way, on October 5, 1943, Schauenburg contacted the German Admiralty and advised them that Operation KIEBITZ had failed.

In the following month, November 20, 1943, the U-536 was sunk by the combined efforts of the HMCS Snowberry, HMCS Calgary, and the HMCS Nene.