By Benjamin Vermette

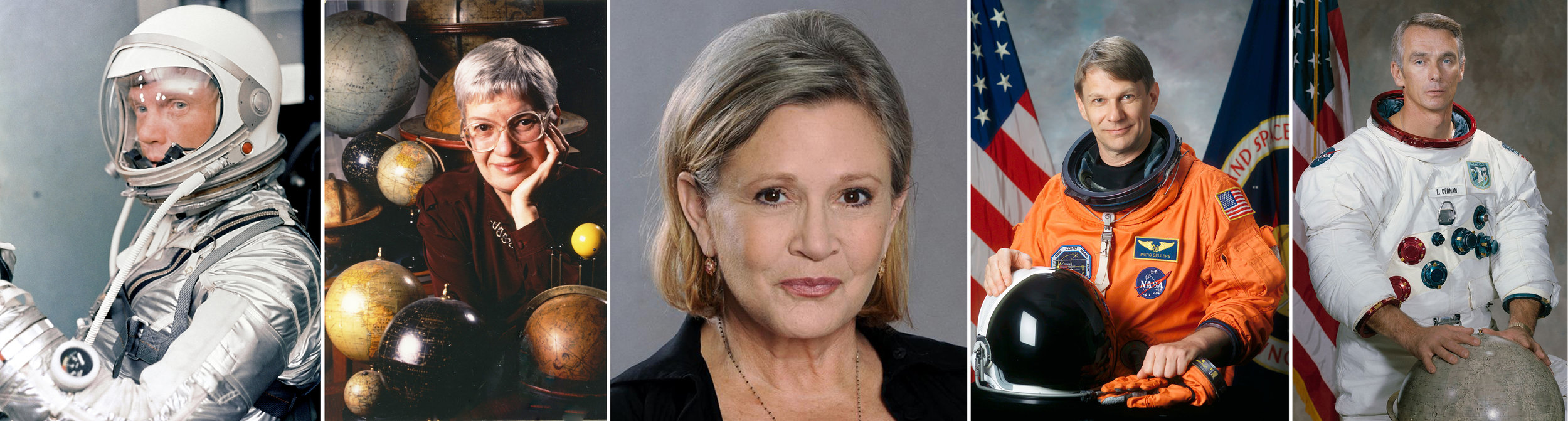

With the loss of David Bowie, Prince, Alan Rickman, Gene Wilder, Fidel Castro, George Michael, Muhammad Ali, Leonard Cohen, and many others, no wonder some speculate that 2016 was one of the worst years ever. Notwithstanding my opinion on 2016 — which I think was pretty great compared to darker times such as 1349 in Europe, when a quarter of Europe’s population died from the Plague — I must confess that the last two months were particularly tough in the “space” world, as we lost at least five great human beings that kept our eyes pointed toward the sky. In their memory, here is the story of the life and death of John Glenn, Vera Rubin, Carrie Fisher, Piers J. Sellers and Gene Cernan.

John Glenn (July 18, 1921 – December 8, 2016)

A true American hero and space pioneer, John Glenn was the exact type of guy you thought of as an astronaut — and that even before he became one. As soon as the United States entered World War II, Glenn joined the military with the idea of becoming a pilot. And that’s just what he did! Logging hours upon hours in the cockpit, Glenn was skillfully becoming one of the Marine Corps’ greatest fighter pilots. After World War II, Glenn flew over 60 combat missions in the Korean War, where he shot down three MiGs and earned two Distinguished Flying Crosses and eight other related medals.

Afterwards, in July 1954, he graduated from the U.S. Naval Test Pilot School in Maryland. As a test pilot, he flew various types of aircraft such as the F8U Crusader, with which he made the first supersonic transcontinental flight in 1957. Flying from southern California to New York City in less than 3 and a half hours, John Glenn made international news for the first time.

A year later, in October 1958 at the beginning of the Cold War, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) was founded. The newly created agency wanted to send a man into space, and was under much pressure to accomplish this goal; it was a feat that would require preparation, experience, and caution. For those reasons, NASA probably thought they should ask well-educated and experienced test pilots to become astronauts.

Well, the thing with John Glenn is that he didn’t meet the first criteria as he lacked a degree in science. In fact, a couple of NASA’s criterions were barely met by Glenn: he was almost too old (40 years old, the limit being 40) and almost too tall (1.79 meters, the limit being 1.80). Nevertheless, Glenn was chosen to be part of a select group of 100 test pilots who met the basic qualifications. After a series of physical and mental tests, he received a call in 1959 asking him if he wanted to be a part of Project Mercury.

After several months of intense training at NASA’s various centres throughout the United States, the competition became increasingly stronger between the seven astronauts as each of them wanted — comprehensively — to become the first man in space. On April 12, 1961, this milestone was reached by Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin. A couple of weeks later, Alan Shepard became the first American in space, leaving only one unattained milestone at the mercy of the six remaining Mercury astronauts: the first American to orbit the Earth.

Unlike Shepard’s 15-minute spaceflight, this second flight was intended to be a five-hour mission, and the perfect guy for this was, you guessed it (or probably already know it), John Glenn. On February 20, 1962, John Glenn, watched by over 135 million people on live television, soared toward the darkness of space on a U.S. Air Force warhead customized to carry the lone man with the goal to complete three orbits of Earth safely. “Zero G and I feel fine,” were Glenn’s first words in space, showing the calm and reassuring nature he possessed even when accomplishing life glorifying exploits.

After splashing down 40 miles short of the planned landing area and being awarded NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal by President John F. Kennedy, John Glenn probably didn’t know the he would not go back to space for another 36 years. Yes, the next time he flew was in 1998 onboard Space Shuttle Discovery. Aged 77, he was NASA’s test subject in trying to better understand zero gravity’s effects on the elderly.

John Glenn, happily sitting in NASA’s jet trainer, the T-38 Talon.

One of the main reasons NASA grounded Glenn in the first place for so many years wasn’t because they viewed Glenn as an incompetent, never-to-fly-again astronaut. On the contrary: as he became the most famous and praised American astronaut — even more so than Alan Shepard — NASA didn’t want to risk his life again by sending him on a risky mission to space. Regarded as a kind of national treasure that needed protection, Glenn finally retired from the agency two years after being the first U.S. astronaut to reach orbital flight to pursue a career in … politics.

In 1964, he ran for the Senate from Ohio; however, an unpredicted injury forced him to resign from the race. Ten years later, in 1974, he was finally admitted in the U.S. Senate as a Democratic member, where he served for 25 years. Note that Glenn also ran for president in 1984, but was unable to win the Democratic nomination.

After a 95-year exhaustively filled life, Glenn died on December 6, 2016, in Ohio. Surrounded by his family, the hero left behind him one of the most inspiring careers an astronaut can hope to achieve, including a second trip to space at 77 years of age after a 25-year career as a U.S. Senator. A role model for everyone, Glenn’s legacy is imperishable.

Vera Rubin (July 23, 1928 – December 25, 2016)

“Watching the stars wheel past [the] bedroom window” was enough to infuse in young Vera Rubin’s mind a spark of interest in astronomy, which later became a passion before becoming her life’s work.

Born in Pennsylvania, Vera Rubin paved the way for women’s greater acceptance in science as her work and observations are considered the driving force behind the discovery of dark matter.

In 1948, she earned her BA in astronomy from New York’s Vassar College, before applying for a graduate program in her field at Princeton. She however ended up at Cornell, where she studied under famous physicist Richard Feynman because Princeton didn’t accept women in the astronomy graduate program until 1975. Her alma maters also include Georgetown University, where she completed her doctoral degree in 1954 by attending classes at night while her husband was waiting in the car because she didn’t know how to drive.

She somehow managed to raise four children — they followed in their mother’s footsteps as each acquired a PhD in natural sciences or mathematics — while focusing on her research and the assistant professorship she earned at Georgetown in 1962.

Now let me resume the outstanding research she is most famous for, which seems even more praiseworthy considering her status as a woman in the male-dominated sphere of 1960s astronomical research.

A young Vera Rubin was already observing the stars when she was an undergraduate at Vassar College, where she earned her bachelor's degree in astronomy in 1948. (Archives & Special Collections, Vassar College Library)

According to Kepler’s laws of motions, the further away a planet is from the sun, the slower it should orbit around it. This implies that innermost planets — such as Mercury, Venus and Earth go around our Sun faster than the outermost planets — Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. If you think about it, it indeed makes sense: the closer a planet is to its star, the stronger it is pulled because of the more intense gravity, so in order to keep moving around the star and not to fall on its fiery surface, it must move faster.

Rubin thought — and rightly so — that if this were true for solar systems and planetary systems, then it must be true for a galaxy. Like any other good scientist, she started observing galaxies using a telescope in order to refute or confirm her hypothesis (that the outermost stars in a galaxy must move slower around the centre of it than the stars that are closer). Astonishingly, she observed that the outermost stars were moving so fast that if the mass of the galaxy were only that of the stars and dust she could see — or everything else one can directly observe — then either the galaxy would have torn apart or Newton’s law of gravitation was flawed. Rest assured, the latter possibility wasn’t the one that explained the observations: gravity still works. Rather, Rubin embraced another possibility, a much darker one, which later proved to be right: dark matter.

The reason why Rubin’s calculations weren’t working was because she didn’t account for all the mass of the galaxies she observed; she was only taking into account normal matter (stars, planets, dust, etc.), whereas dark matter was to be considered as well.

On large-scale systems, such as galaxies, dark matter’s effects are so notable that they significantly increase the system’s mass, consequently increasing the speed of the celestial objects that orbit around its centre (in galaxies, the celestial objects are mostly stars).

While we now know that dark matter contributes to roughly 25% of the ‘content’ of the Universe, concretely explaining what it exactly consists of is a more arduous task. Note that ‘normal’ matter makes about 5% of the Universe, while dark energy — a different thing than dark matter — makes up 75%.

As a leading female scientist, Vera Rubin obstinately persevered to finally find a satisfying answer to her observations. She was indeed right when she said that “science progresses best when observations force us to alter out preconceptions.”

She passed away on Christmas Day, leaving the gift to find dark matter’s nature to the future generation of astronomers.

Carrie Fisher (October 21, 1956 – December 27, 2016)

We all remember watching Star Wars IV: A New Hope for the first time and feeling impressed when this beautiful, charismatic and powerful leader named Princess Leia famously recorded herself using R2-D2 to seek help: “Help me Obi-Wan Kenobi, you’re my only hope.”

However, even if she was Princess Leia in the hearts and minds of many, Carrie Fisher was a lot more. Actress, author and humourist, nothing seemed to be quite enough. In June, she announced she was going to be columnist for The Guardian, providing help to people suffering from mental health problems. A genuine altruist, Carrie Fisher inspired many.

Actor, author, humourist, Carrie Fisher will be tied to Star Wars' iconic Princess Leia. (still from the 1977 original Star Wars film)

Unfortunately, just as Princess Leia’s mother died of exhaustion shortly after her birth (see Star Wars III: Revenge of the Sith), Carrie Fisher’s mom, Hollywood legend Debbie Reynolds, passed shortly after her death, on December 28.

She will be missed, and her legacy on and off the screen will be remembered, and the rebellion will persist as long as peace is not restored in the galaxy, as long as the Force is unbalanced, as long as it is the will of Princess Leia’s soul.

Piers J. Sellers (April 11, 1955 – December 23, 2016)

A NASA astronaut and veteran of three Space Shuttle missions, Piers J. Sellers wasn’t like the others: instead of encouraging us to look up and to dream about the wonders of space, he urged us to look down at the Earth and to realize the seriousness of its disastrously changing climate.

Born in England, Sellers moved to the United States in 1982 to work as a climate researcher at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in Maryland. He applied to be an astronaut in 1984, but was unfortunately turned down because he lacked a U.S. citizenship. In 1991, he was granted U.S. citizenship and, five years later, his application to NASA’s astronaut program was accepted.

Piers Sellers joined the NASA astronaut corps in 1996 and flew to the International Space Station in 2002, 2006 and 2010, performing six spacewalks and various space station assembly tasks. As STS-112 mission specialist, Sellers is pictured above on the aft flight deck of the Space Shuttle Atlantis in 2002. (NASA photo)

His first spaceflight was in 2002 on Space Shuttle Atlantis. He conducted his first spacewalk on his inaugural flight, logging more than 20 hours outside the spacecraft with a total of three sorties. He later flew on Discovery in 2006 and again on Atlantis in 2010. A year later, in 2011, he announced his retirement from NASA, where he had also been director of the Earth Science Division at GSFC.

In January 2016, he announced he had been diagnosed with cancer with only a few months to live, thus motivating him to “live life at 20 times normal speed.”

Sellers was an astronaut, but his legacy will mostly be remembered in terms of climate, as he was an expert in the field. He appeared on Leonardo DiCaprio’s 2016 climate-change documentary Before the Flood and was addressed by many as a driving force in climate research.

By seeing the Earth as a fragile blue rock flying through darkness, he thought that, for the sake of humanity, we need to protect it, for he knew it was the only place we could live. He had a privileged perspective in addressing climate change, so let his message be clear:

“Here are the facts: The climate is warming. We’ve measured it, from the beginning of the industrial revolution to now. It correlates so well with emissions and with theory, we know within almost an absolute certainty that it’s us who are causing the warming and the CO2 emissions. Because it’s warming, the ice is melting, and because the ice is melting and the oceans are warming, the sea is rising.”

Eugene Cernan (March 14, 1934 – January 16, 2017)

The last person I shall address in this eulogistic article is the last man to have walked on the moon, Eugene Andrew Cernan, or simply Gene. The Gene. As one of my favourite astronauts, Gene Cernan is the exact type of guy every young man wants to be at some point in his life: cocky and arrogant, but also crazy smart and skilled.

Like many Apollo-era astronauts, young Gene Cernan was a Boy Scout as he grew up in the suburbs of Chicago. In 1952, he went on to study at Purdue University, earning a Bachelor of Science in Electrical Engineering in 1956, before earning a scholarship to become a U.S. Navy ensign. Two years later, Cernan became a naval aviator, while starting to study for a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering, which he earned from the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in 1963. As a pilot, he logged more than 5,000 hours in an aircraft, 4,800 of which were in a jet.

In October 1963, shortly after earning his master’s degree, he was selected as a NASA astronaut alongside Buzz Aldrin — the second man on the moon — and 12 other men in what was known as NASA Astronaut Group 3. It would be interesting to consider how devoted to space exploration and how courageous these men were to serve as “spacemen” because being an astronaut in the 1960s wasn’t as safe as it is now. For instance, from the 14 men that were selected as part of NASA Astronaut Group 3, only 10 went to space — the other four were killed during training, either in a jet crash or in a capsule fire during a mission simulation.

Cernan’s first spaceflight wasn’t actually supposed to be his first: he was selected as backup crew for NASA’s Gemini 9 manned spaceflight mission, which was scheduled to launch in June 1966. However, Cernan and his colleague Thomas Stafford became the prime crew when Elliot See and Charles Bassett were killed in a T-38 Talon plane crash in Missouri. During this spaceflight, Cernan became the second American and the third person ever to perform an extra-vehicular activity (or EVA, a fancy word for spacewalk), but a couple of things went wrong and he was forced to cut the EVA short.

He served as Lunar Module Pilot for Apollo 10 on his second spaceflight in May 1969 — two months before Neil Armstrong’s “giant leap for mankind.” Cernan’s spaceflight was a trial run — except for the actual landing and walking on the moon part — for the history-making Apollo 11, in which Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin landed and walked on the moon for the first time. Cernan once told journalists that NASA intentionally cut in the Apollo 10 Lunar Module’s fuel in order to prevent the crew from landing on the moon, because had NASA given the crew enough fuel to land on the moon and come back, Neil Armstrong probably wouldn’t be as popular.

His third — and last — spaceflight was in December 1972, when he served as commander of the last lunar landing mission, Apollo 17. He is one of the only three astronauts that went to the moon twice. Note that Cernan declined an offer to be the Lunar Module Pilot of Apollo 16 because he wanted to command his own mission.

Eugene Cernan commanded the Apollo 17 spacecraft in December 1972 and was the last man to leave the moon as the NASA Apollo lunar landing program was cancelled shortly after. (A still from a 2013 YouTube interview on space programs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MvcmhHCVijU)

The last words spoken on the surface of the moon were Cernan’s:

“Bob, this is Gene, and I'm on the surface; and, as I take man's last step from the surface, back home for some time to come — but we believe not too long into the future — I'd like to just [say] what I believe history will record: that America's challenge of today has forged man's destiny of tomorrow. And, as we leave the Moon at Taurus–Littrow, we leave as we came and, God willing, as we shall return, with peace and hope for all mankind. Godspeed the crew of Apollo 17.”

We hope you were right, Gene.

He passed on January 16 at age 82. I was particularly saddened when I heard about his death, knowing that Gene wasn’t so keen about his title of ‘last man on the moon’: rather, he was “quite disappointed [to be] the last man on the moon.”