By Robert Smol

In spite of growing evidence on the sorry state of the Royal Canadian Navy, both the previous Conservative and the current Liberal governments have stalled on modernizing our fleet citing budgetary restrictions.

And while there are much-delayed plans for replacements coming in the next few years, our navy will, for the foreseeable future, have to try and fulfill its obligations with a much reduced fleet and corresponding capability.

But is this really a budgetary problem, the classic either/or debate of defence versus social programs, or is it more a failure of our collective national will? A failure that we may think we can afford to live with in the naïve assumption that the U.S. military will always be there to protect our coastlines at no apparent political cost to us?

Or would it be possible for a country to have a modern well-equipped military and still be able to provide the social programs at an equal or (if I may dare to dream for a moment) a greater level than today? Does it have to be the old “bullets versus butter” argument, or can we actually fire and feast on both?

At least one perspective on this answer can be found in the defence and procurement decisions made by the one Scandinavian country with which Canada shares a somewhat disputed boundary in the Arctic.

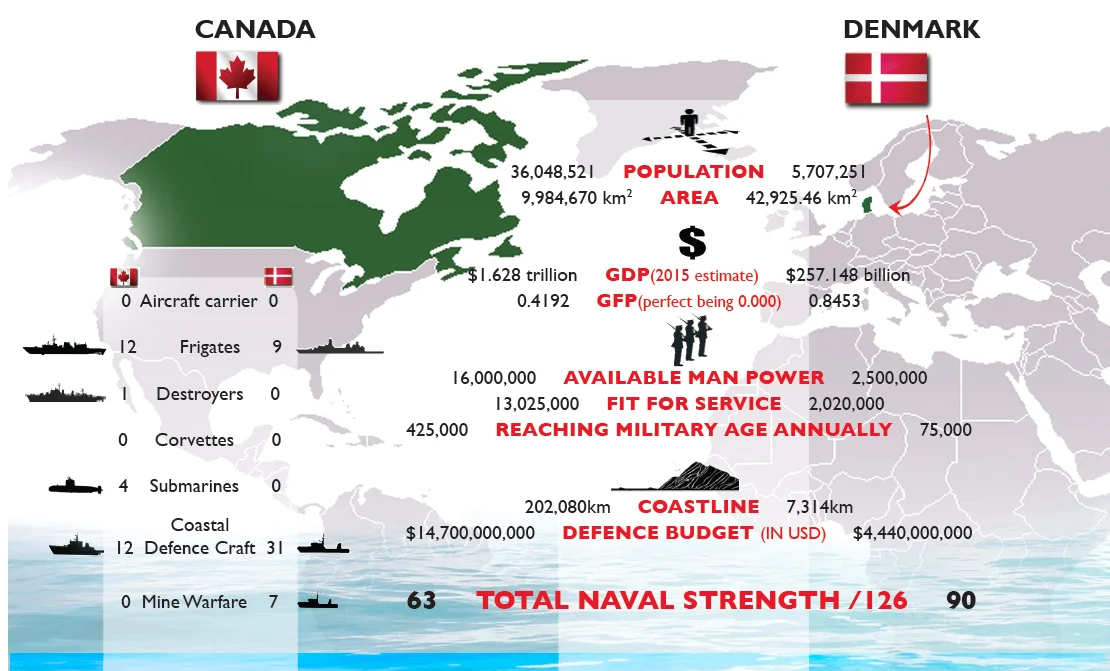

Denmark is a much smaller country than Canada and its citizens enjoy generous social welfare policies; it has also managed to modernize its military (including its navy) to an extent that we Canadians can only dream of today. We may impulsively assume that on all fronts the Royal Canadian Navy, even in its struggling state, can outdo the naval capability of this small social democratic country, which provides five weeks of paid vacation, generous maternity leave, as well as tuition-free post-secondary education to its citizens. Think again folks!

Yes, Canada’s fleet has more ships and sailors. But consider the areas of new technology, arms, equipment, logistical, and special operational support, and a different perspective emerges.

As Canada scrapped all but one of its 44-year-old air defence destroyers and dallied and defaulted on its plans for an eventual replacement, Denmark constructed three air defence frigates, the last of which became operational in 2012. Today, these three Iver Huitfeldt-class frigates serve as the country’s main warships. Praised by the U.S. Navy for its low cost and flexibility, the Iver Huitfeldt’s impressive armament consists of six vertical launching systems (VLS) containing up to 32 SM-2 111A surface-to-air missiles and up to 24 RIM-162 Raytheon Evolved Sea Sparrow Missiles. It also operates 8 to 16 Harpoon Block II ship-to-ship missiles and 2 dual MU90 Impact anti-submarine warfare (ASW) torpedoes. In addition, its close-in weapon system (CIWS) consists of an Oerlikon Millennium 35mm gun. Finally, the ship has two OTO Melara 76mm guns.

Where Denmark literally shuts the Royal Canadian Navy out is in the area of support ships. Today, the Royal Danish Navy has two armed Absalon-class multi-role support ships that became operational in 2005. The vessels carry the same basic configuration as the Iver Huitfeldt-class air defence frigates and can serve as a command platform for land, air and naval forces with additional employability as a transport, hospital ship or minelayer. The Absalon’s impressive armament includes a 5-inch 54-caliber Mark 45 Mod 4 naval main gun, as well as two Rheinmetall Millennium 35mm CIWS with an additional six 12.7mm machine guns. Its missile arsenal consists of 16 RGM-84 Harpoon Block II anti-ship missiles, 36 RIM-162 surface-to-air missiles and two FIM-92A Stinger Missiles and MK32 Mod 14 launchers.

By 2015, HMCS Protecteur, the last of Canada’s two remaining — and considerably less-armed — auxiliary oiler replenishment (AOR) ships was taken out of service following a fire at sea with no replacement in sight for a few years. Meanwhile, logistical support for Canada’s naval fleet will soon be provided by the MV Asterix, a container ship that is being converted into an auxiliary vessel.

Today, the oldest frigates in the Royal Danish Navy are the same age as our newest and only oceangoing frigates. Designed and built in Denmark, the Royal Danish Navy has four Thetis-class frigates, which have been in service since 1991. Not quite as well-armed as Canada’s Halifax-class frigates, these ships nonetheless have a limited icebreaking capability (important for a nation concerned about Arctic sovereignty) and are armed with OTO Melara 76mm Super Rapid machine guns as well as two 20mm Oerlikon guns and depth charge throwers.

Admittedly, when it comes to submarines Canada does shut out the Danes, who retired the last of their six diesel subs in 2004. But whether or not Canada’s four problem-plagued, second-hand submarines built in the early 1990s will offer us any real advantage as they chug through their third decade of existence remains somewhat problematic.

So too must technology and capability be considered should we compare our respective fleets of smaller coastal patrol vessels. In the last few years, while Canada took some of its 12 aging Kingston-class Maritime Coastal Defence Vessels (MCDVs) out of service for lack of funds, Denmark constructed two separate classes of armed offshore patrol vessels.

First launched in 2008, Denmark has three Knud Rasmussen-class offshore patrol vessels. And while Canada still eagerly awaits the much-delayed completion of its first Arctic/Offshore Patrol Ship (AOPS), the Danish ships are currently operational and conducting sovereignty patrols in the Arctic. The Knud Rasmussen’s main armament consists of a 76mm gun as well as two 12.7mm heavy machine guns. Its missile armament consists of RIM-162 Evolved Sea Sparrow surface-to-air missiles. It also has a MU90 Impact torpedo and an aft helicopter deck.

The Royal Danish Navy also has six Diana-class patrol boats completed in 2007 and armed with 12.7mm heavy machine guns. All this is in addition to a number of other smaller auxiliary vessels, including six environmental protection and two training boats that are still in operation.

And how do our 12 MCDVs, launched in the mid-1990s, compare? Numerically superior and older, Canada’s Kingston-class ships, whenever they are not laid up, are now poised to fight for Canada with a WWII-vintage 40mm Model 60 rapid-fire gun and two 12.7mm machine guns. It has no helicopter deck.

And how much better armed and ready to actually fight for Canada will our five AOPS boats be once they are all completed sometime in 2019? According to official documents, the only planned armament for these ships will be a BAE MK 38 gun that, in the words of the Royal Canadian Navy, is “to support domestic constabulary role.” Translation: not going into wartime combat with that! Which probably explains why, in November of 2014, the commander of the Royal Canadian Navy, Vice-Admiral Mark Norman, stated to a parliamentary committee that the planned AOPS are “not being built or delivered to deal with the Russians.”

And, ship to ship, they will never have a hope in hell against the Royal Danish Navy either!

But there is more. The Royal Danish Navy also has a tactical special ops arm that can outgun anything that our Navy can serve up in comparison. For its part, Canada has only recently stood up its first squad of 13 specially trained sailors, the so-called Enhanced Naval Boarding Party (ENBP). In comparison, Denmark has had its own Frogman Corps since the 1950s, organized along the line of Britain’s Special Boat Service (SBS). Their tasks include reconnaissance as well as tactical assault of enemy craft, sabotage and anti-terrorism. Understandably, a residual capability to conduct these operations might exist somewhere else in the Canadian Armed Forces. However, the only navy personnel promoted to the public as specially trained to conduct these specialized tactics are our combat-qualified ENBP sailors.

The Royal Danish Navy also has administrative control over the nation’s specialized winter long-range Arctic sovereignty patrol unit (the Sirius Sledge Patrol) that continually and in all types of weather patrols and enforces Danish sovereignty on the island of Greenland. As with the Frogman Corps, training for the Sirius patrol is extensive and demanding.

By way of comparison, Canada has tasked Arctic sovereignty to our minimally trained Canadian Rangers, who carry WWII-era rifles and receive all of 10 days of training. Perhaps thankfully, our Navy need not take any direct responsibility for them.

What is the lesson to be learned here? Perhaps it is time to shift our planning and procurement focus away from North America and start looking squarely and honestly at how NATO allies, much smaller than us, are actually doing more with less. Then we must ask how we can emulate them.

In the meantime, I know where I will place my bets in the highly unlikely event of Canadian and Danish warships facing each other on the open seas or along our Arctic coasts.