(Volume 24-4)

By Bob Gordon

Note to readers: Unexpected health complications and hospitalization necessitated a delay in publication of the third and final installment of Bob Gordon’s series linking the 38 years of General Sir Arthur Currie’s pre-war life to his success on the battlefield and ascent to the position of commander of the Canadian Corps in June of 1917. We are happy to report he is back in writing form! The final installment in the series follows.

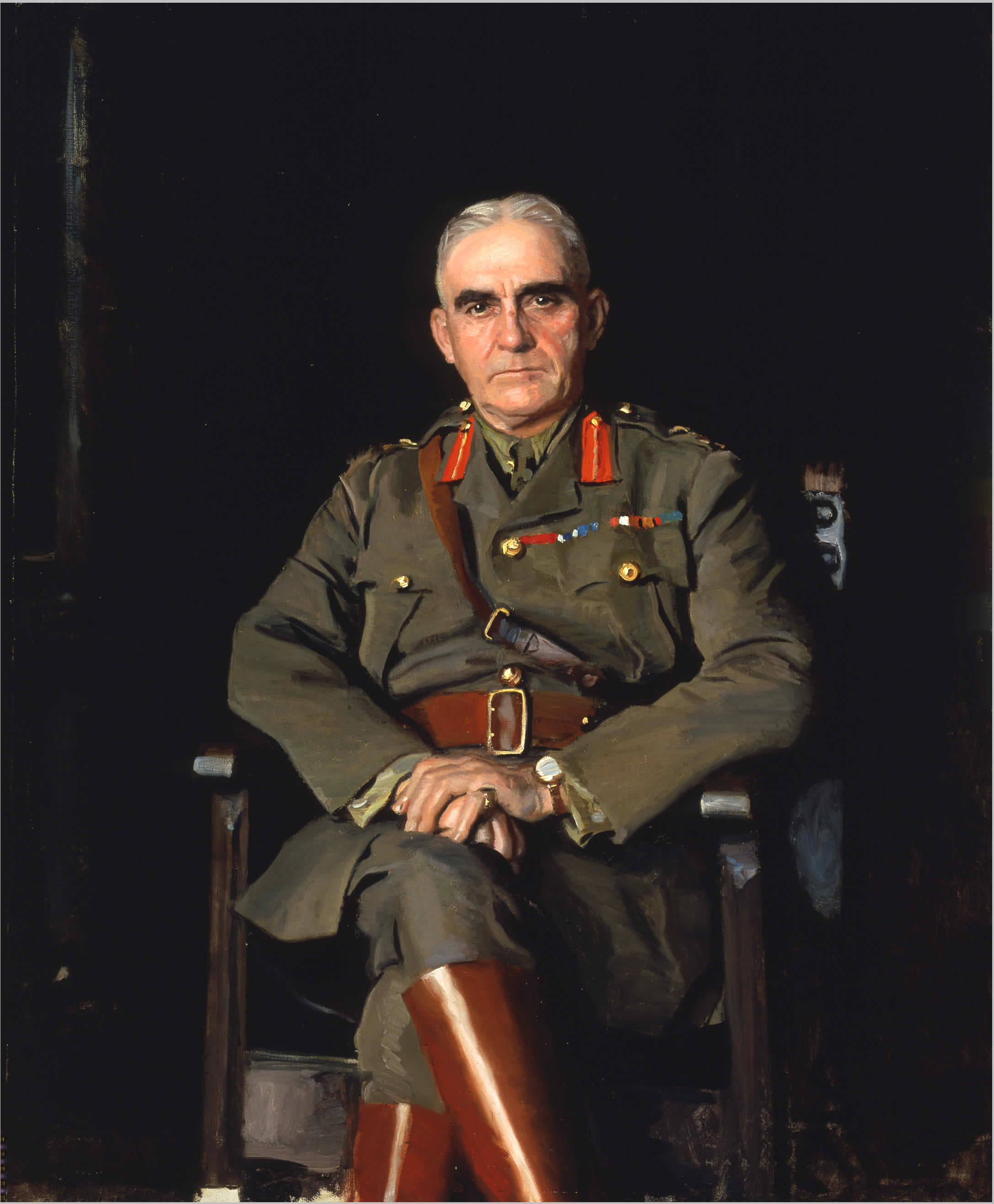

The first Canadian-born commander of the Canadian Corps, Arthur Currie rapidly rose to the heights of military authority within the Corps and influence beyond it. Jowly and bottom heavy, alone among senior officers in the British Army to disdain a moustache, only his eyes, both placid and piercing, betrayed his intellect and fierce independence. Three years from a faltering land boom on Vancouver Island, he led the most potent fighting force on the Western Front. From the beginning, praise was unstinting. Before having even left Canada, while still at Camp Valcartier, after a meeting with the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Borden confided to his diary that he was “impressed.” On Salisbury Plain, six months later, divisional commander Lieutenant-General Edwin Alderson regarded him as “out and out the best” of his brigadiers.

Currie’s military career and accomplishments, and his dual denouement as academic administrator and subject of scurrilous rumours culminating in a very public libel trial, have all been explored frequently and thoroughly. However, his prewar life remains largely unexplored. The published sources have all relied heavily on Hugh M. Urquhart’s Arthur Currie: The Biography of a Great Canadian. The previous instalments in this series have established that it is demonstrably false and flies in the face of the documents. Simply put, current understanding of Currie’s life to 1914 is ludicrously saccharine and sanitized.

In an article in Canadian Military History about the prewar life in Edmonton of machine gun innovator Raymond Brutinel, author Cameron Pulsifer makes a point about the historiography of his subject that is equally true of Currie. “No real attempt has been made, however, to undertake the necessary research that would allow for an in-depth examination of this formative period of his life, for what it might reveal about the experiences he had that helped to shape him, and what they reveal about his developing personality and character.” The preceding articles in this series provided a preliminary survey of Currie’s 38 prewar years, based on the sources, unblinkered by Urquhart. It allows these four decades to be woven into his whole life story. Now, his relatively brief but spectacularly successful military career needs to be fit into this same life story, as one episode in a sustained narrative of a “developing personality and character.”

Currie’s story is that of a man born to the rural yeomanry of Upper Canada, who also made, and lost, his own fortune. It is that of a self-made man, accustomed to marching to his own drummer. Currie was not necessarily a leader, but he definitely was not a follower. His civilian careers demonstrate that he was an enterprising individual willing to blaze his own trail. At the same time, however, he was also risk-averse. His big gamble, his real estate speculation, wrecked him and almost killed him financially. Currie had been stung by speculation. Arguably, this shock only reinforced a trait already innate. He was not one to ‘roll the dice’ until the odds were stacked in his favour, as they were when he left school for Victoria with a grubstake and welcoming accommodations with extended family awaiting.

The shift from pedagogue to insurance salesman was the most radical career choice he made in his life. It was made during months of illness and convalescence. It can hardly be described as rashly made in the heat of the moment. Again, regardless of the fact that speculation was on the verge of destroying him financially by 1914, he was innately conservative and incremental. He made three moves in his teaching career of only five years. First to Sydney, a hamlet north of Victoria. Then back to a school in the city at the first opportunity. Finally, he finished his brief career as a teacher having moved on to the best collegiate in Victoria. Methodically, Currie followed a definite path to the pinnacle of the teaching world on Vancouver Island.

Naturally risk-averse and burned by speculation, his mindset was fertile ground for a way of war that demanded that one must bite and hold, taking small, systematic steps toward the objective. A mind that knew speculation about a shattering breakthrough was a Chimera — a fire-breathing monster with a lion’s head, a goat’s body, and a tail that ends in a snake’s head — and an unrealistic and never attainable myth. Patience, painstaking preparation and measured, manageable objectives characterized Currie’s prewar life and defined his approach to combat. Nowhere was this more evident than at the battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917. The Canadian Corps was not chasing a war-ending breakthrough at Vimy. Four carefully defined objective lines were to result in Canadian control of the heights. Vimy was a methodical, incremental attempt to achieve a measured and manageable goal, nothing more and nothing less.

On another level, the battle also demonstrates that Currie remained both a fluent teacher and effective trainer, but also an avid and successful student when he was motivated to perform: A factor apparently lacking during his lacklustre performance at Strathroy Collegiate.

When the Canadian Corps was ordered to provide an officer to examine and analyze the French experience at Verdun, Lieutenant-General Sir Julian Byng selected Currie. Walking the ground and speaking to combatants, Currie was to distil the lessons learned, focusing on the successful French counterattacks in the battle’s final phases. He was then to introduce those lessons to the four divisions of the Canadian Corps. His performance as a student of the French battles at Verdun and then a teacher of those lessons to the Canadian Corps was one of his most successful, influential and important achievements.

Success at Vimy largely followed from a significant change in the Corps’ tactics. According to Mark Osborne Humphries, “for Arthur Currie, the most important lesson of Verdun was that a flexible doctrine employing self-reliant platoons could solve the riddle of the trenches.” It did and marked the ascension of the Canadian Corps to its premier role within the Imperial Army. Battlefield confusion coupled with unreliable communications led Currie to conclude that the French decision to devolve decision-making and firepower was the key to their success. Currie proposed that the Corps integrate specialists into every platoon. Previously, as specialists they had been under battalion or brigade command. Now, each platoon CO would have direct control over them. The platoon was reorganized in four sections of riflemen, bombers, rifle-grenadiers and Lewis gunners. Currie introduced this revolutionary idea and oversaw its implementation.

However, his success as a trainer can hardly be seen as surprising. Prewar school board trustees had praised his students’ orderliness and performance. Within the militia, he had progressed rapidly and his units were constant medalists based on the quality of Currie’s training regimen. The combat value of the Dandy Fifth’s militia training was not worth the powder to blow it up, but it is evident that Currie knew how to teach and to train.

Currie was open to learning these innovative lessons because, counter-intuitively, his utter lack of combat experience and instruction with modern weaponry was an advantage. He had neither tactical or technological training of relevance and, consequently, nothing to unlearn. In many senses he was a tabula rasa, with no preconceived notions of tactics he had to be disabused of. He was open-minded, willing to learn and able to impart this newfound knowledge to the Canadian Corps.

Demonstrably flexible and original, based on the creative Nanaimo operation, he was open to observe and analyze the reality of industrial warfare, and apply the lessons learned to its conduct. Currie’s willingness to see the radical solution of converting the platoon into a combined arms team, and his ability to introduce this reorganization to the Corps at large, follows logically from his prewar success as a militia officer and teacher. He was at the very heart of the revolutionary reorganization of the platoon that vastly increased its firepower and the Corps’ combat effectiveness. Currie learned the lessons of Verdun and taught them to the Canadian Corps: Hardly surprising considering his prewar success as a teacher.

Promoted to Corps commander in the wake of Vimy Ridge, his first battle at Hill 70 revealed a great deal about Currie‘s transferable, civilian skills. He possessed extraordinary geographic intelligence, not surprising from a speculator and developer, and the considerable self-assurance of an entrepreneur. The office full of maps, the ability to call to mind the details of myriad lots, the entire practice of land purchase and development refined Currie’s awareness of the lay of the land. Currie could read the maps, observe the ground and integrate his plans into its constraints. Nowhere would this be more evident then in August 1917 as the Corps advanced towards Lens.

On July 7, 1917 the First British Army ordered the Canadian Corps “to take Lens with a view to threatening an advance on Lille from the south.” Lieutenant-General Arthur Currie, the newly minted Canadian Corps commander, didn’t approve of the order. He believed that an alternative plan would divert and destroy more Germans, at less cost to the Canadians than an assault on Lens. Involved in planning his first battle as a Corps commander and a Canadian militiaman amongst professional British officers, Currie, remarkably boldly, argued for his alternative at a conference of Corps commanders on July 10. Currie proposed that the Canadian Corps capture Hill 70, a dominating point of ground immediately north of Lens. Control of Hill 70 would make retention of Lens an impossibility as troops on Hill 70 could enfilade Lens and, from its heights, direct artillery fire on the city.

Therefore, Currie continued, the Germans would be forced to counterattack to retake Hill 70 and Canadian fire would engulf them. Currie proposed to distract the Germans and destroy those that fell for the ruse. Currie carried the day. First Army issued an entirely new set of orders to the Corps that “place[d] the whole of the operations for the capture of Lens in the hands of G.O.C., Canadian Corps [Currie].” The new orders also changed the Canadian objective from Lens to “the high ground N.W. of the town [Hill 70].” Currie had converted the Battle of Lens into the Battle of Hill 70 based on his reading of maps and the ground. Independence, innovation and geographic intelligence are entirely congruent with Currie’s civilian career in Victoria. The Battle of Hill 70 epitomizes his practical experience as a developer and the mindset of an independent, self-confident entrepreneur.

His life experience as an independent entrepreneur and his position as an absolute military novice in April 1914 render entirely understandable Currie’s actions in the wake of the German gas attacks on the Ypres Salient in April 1915. The initial German gas attack broke the French forces on Currie’s left flank leaving a gaping hole in the Allied lines. Currie’s 2nd Brigade risked being isolated, faced the real possibility of German troops pouring through the gap and assuming positions behind his troops as they endured a subsequent German gas attack from the front. British troops were visible in reserve and able to protect his exposed flank, but they refused to respond to Currie’s entreaties to assume the necessary positions without orders from a senior British officer.

Currie made the unorthodox decision to leave his headquarters and venture to the headquarters of the senior British officer to explain the situation and make a personal appeal for help. His harshest critics have condemned this approach as irresponsible, even a dereliction of duty. While this was certainly not a textbook approach to the situation, it is no surprise when one is aware of his prewar civilian experience as an independent businessman. While his efforts proved ultimately unsuccessful in that he received nothing but a severe dressing down, he had left his battalion COs explicit orders as to how to proceed in his absence and was simply taking the reins in hand as any self-confident and independent businessman would in civilian life. His approach is entirely understandable when one factors in his civilian life experiences.

Moving into the realm of pure speculation, his prewar civilian life also offers fertile ground for explaining his contentious relationship with former Minister of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes, in the years following the war. By Armistice Day, Hughes had developed an almost pathological hatred of Currie and, within the protected confines of Parliament, had no problem labelling Currie a vainglorious butcher. He was particularly offended by Currie’s disdain for his son, Garnet Hughes, and his ability (or rather lack thereof) to command in combat. Currie resisted Garnet’s appointment as CO of an active front-line division because he did not believe he was up to the task. However, Hughes seems to have regarded this as a personal slight and was enraged.

Perhaps Hughes was unable to accept the shifting dynamic between the two men. Arguably, Hughes continued to see Currie as the prewar militia officer who owed his advancement to the omnipotent but beneficent Sir Sam and expected fealty in return. For both reasons, Hughes may have been unable to see that, as his star had fallen, Currie’s had risen. All Hughes seems to have been able to see was that a prewar militiaman was no longer doing what he was told.

General Sir Arthur Currie’s time in the Canadian Expeditionary Force was not the final act in his life story. After the war, he would go on to a successful career as Principal of McGill University. However, neither was it the first chapter of his life. Understanding his success in the Canadian Corps is impossible without a clear appreciation of the 38 years he lived before he put on a regular army uniform at Camp Valcartier.