(Volume 23-12)

By Cord A. Scott

“If the troops like the cartoons I can thank my army experience more than any other one thing. Because no matter how well you can draw, you can’t get that feeling of live humor into an army cartoon unless you’ve experienced the things you’re trying to put into black and white. You’ve got to live it first.” — Bing Coughlin, This Army

“It will serve as a reminder that during the most trying periods the Canadian Army always retained a sense of humour.” — General H.D.G. Crerar, Maple Leaf Scrapbook

When the Second World War began in Europe, Canadians from all walks of life and a multitude of different jobs answered the call to defend the British Empire.

Given the country’s strong familiarity with American media, in addition to the older British tradition of enlisted men’s papers, it was not surprising that the venerable comic panel became a much-utilized creative outlet for Canadian soldiers. These cartoons allowed men in the field to enjoy a laugh while dealing with the harshness of war.

As with the American military, one cartoon character has come to dominate the Canadian soldier’s service: William “Bing” Coughlin’s Herbie, who was featured in This Army. A variety of other comics were also in circulation, depicting soldiers in different regions and conditions, and confronting different struggles.

Most cartoons came from two principal sources: armed forces papers and weekly magazines. These were akin to the editorial cartoons or Sunday funnies from the newspapers many soldiers would recognize from their civilian life. There were also personal sketches that were compiled into some form of booklet and were sold as a souvenir to the troops.

There were plenty of publications for Canadian Armed Forces personnel to choose from: Khaki, The Maple Leaf, and Wings Abroad, as well as front-line papers like the Big 2 Bugle and The Column Courier.

The cartoons served several valuable purposes. First and foremost, they were used to entertain. They were a way for personnel to vent their frustrations in an innocent manner.

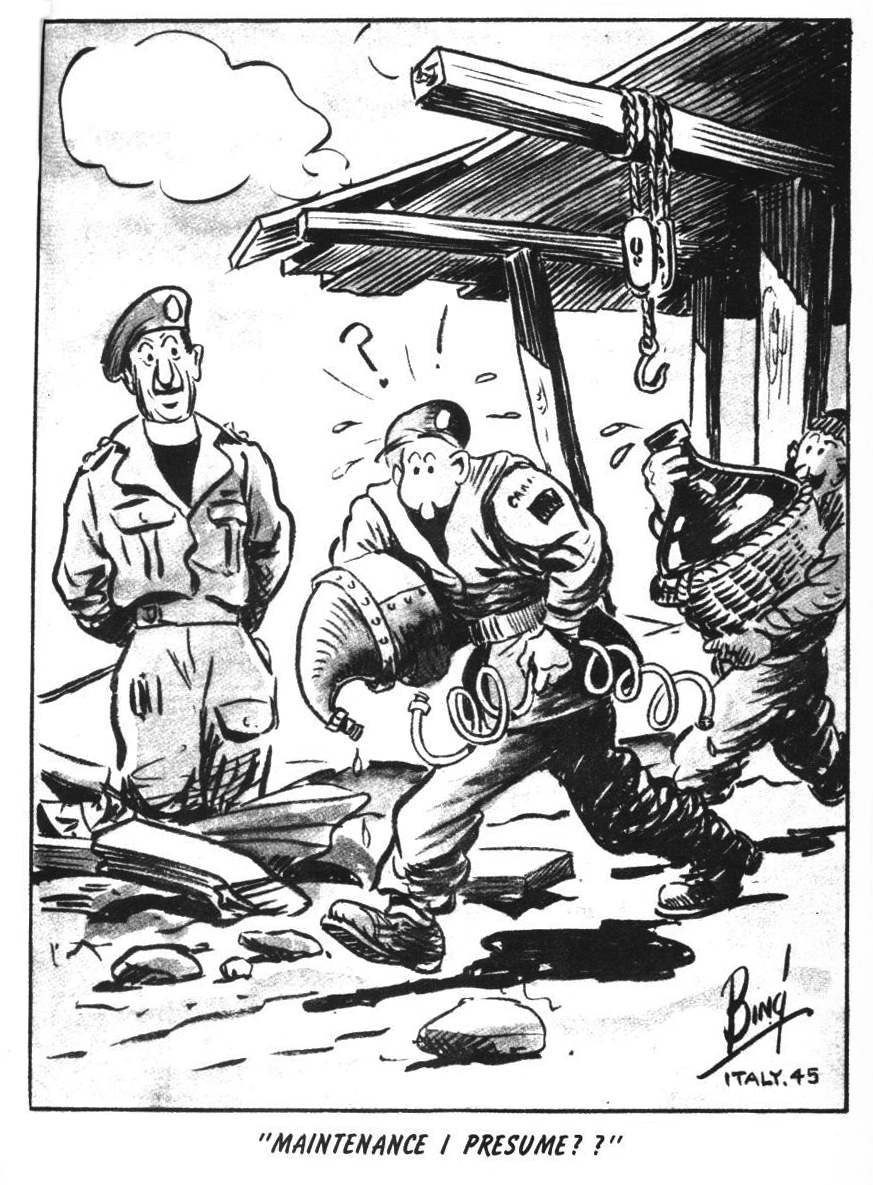

They were also used to educate. For example, illustrations by Len Norris were adopted as part of the Canadian Army’s training regimen. His cartoon posters were created to show how to properly maintain equipment.

The importance of wartime cartoonists was recognized at the time. There was even a book on the major artists and their work: War Cartoons and Caricatures of the British Commonwealth, by Alan Reeve, published in 1941. Among the artists acknowledged in the book were British artist Bruce Bairnsfather (famous for the Second World War cartoon “If you can find a better ‘ole”) and Canadian artists such as David Low and Les Callan.

For most of the artists profiled in the book, fame would come after war’s end. Only Callan was a known artist at the time of the book’s publication.

One of the universal experiences of any military service is the transition from civilian to military life. Several Canadian artists attempted to capture the essence of basic training in their cartoons.

One of the earliest attempts at this was made by H. Stewart Cameron, who drew a series of cartoons that were bound into a leaflet called Basic Training Daze: Candid Cartoons of You and Me in the Army. Cameron illustrated the chaos of basic training: marching in formation during the first week, gas chamber training and mess hall. He was also quick to note how difficult it was to handle weapons like a Bren gun, which bounced all over during discharge. The cartoons were meant to make light of training that was often trying.

Vancouver cartoonist Len Norris was another artist whose illustrations made light of training. Norris’s initial job for the Canadian Army was to illustrate training and education posters for the department of military maintenance. Interestingly, this mirrored American comic book illustrator Will Eisner, who was working for the Aberdeen Proving Ground, creating posters for Army Motors, a U.S. Army training manual.

Norris produced a book about his experiences in cartoon form, entitled “Private” Reflections, with text and poems by Paul Zemke. The book contains reflections on everything from gas masks and parade drills to comments on the fairer sex (“Hey look! Real legs!”). There were even comments on how the Yanks were different in their approach to war. One private says to another as shells whip by, “If you were a Yank you’d get the Purple Heart for this, chum,” as the second man’s head came off — sarcasm and understatement at their finest.

The comparison between Norris and Eisner is no coincidence. Given the sharing of equipment and supplies between Canadian and American troops, and the need to maintain them effectively, articles appearing in American and Canadian publications would frequently be shared. It was natural, therefore, that the two would develop similar forms of entertainment and illustrations to augment military training or doctrine.

One book that captured the essence of air training in Canada was Dat H’ampire H’air Train Plan, by Carroll MacLeod and illustrated by H. Rickard. This book, which was first written in 1943, described the training regime of the RCAF. The book, which was told through verse as well as cartoons, ended with the crew of a Halifax bomber being shot down, escaping, and making their way back to England.

Several cartoons tried to embrace the concepts of training in Canada or overseas before they saw combat. Another example of training as a subject is found in the book The Canadian Field Artillery. Several cartoons noted the increased training schedules that were instituted while in England. What made these cartoons unique, however, is that they were drawn not by an enlisted man, as is often the case for many war cartoons, but by Lieutenant P.P.F. Clay. His drawings depicted life in England, where the training was undertaken before the inevitable landings in France. Another thing that made these illustrations unique was the fact they depicted a unit from training in England, through to actual combat in Europe.

Regardless of where an individual soldier trained, the topics of complaint were universal. Shared experience allowed soldiers the ability to vent to one another and bond over shared struggles. For example, a cartoon might depict the bitterness of soldiers who are forced through harsh and rigorous training, while their officers sipped spirits and discussed tactics.

This sort of humour was critical to the morale of the Allied fighting men, and served as a way to inform and amuse. It offered a release for those who were either unsure of how they might react to combat, or had seen the horrors of war and wished to vent in a way that those who understood would appreciate. These comics were an essential part of military life and continue to this day.

Italian Campaign and the fame of Herbie

Of all the cartoons drawn by military artists, one inevitably stands out for the troops. For the American GI, it was the characters Willie and Joe, as they appeared in Stars and Stripes. For the Canadians, the most recognized figure was the “everyman” that slogged through the mud and suffered: Herbie. The creation of “Bing” Coughlin, a sergeant with the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards, Herbie was similar in form to Kilroy. He had a big nose, was often involved in a variety of mishaps, and was definitely a citizen soldier, not a professional career type. He was also a man who enlisted with the goal of getting the job done. The cartoon character came from the Mediterranean theatre, where the fighting and harsh conditions of Italy created the need to laugh.

Coughlin illustrated many of the similar hardships and general complaints that abounded in any army: lack of food, horrible weather, and the need to constantly dig in. More importantly, Herbie was the illustrated member of the Canadian ground forces who, at that time, were seeing their first significant, sustained fighting. While the military ventures of Hong Kong in December 1941 and Dieppe in July 1942 were significant for the Army as a learning exercise, the landing at Pachino in July 1943 was the first real experience that the Canadian Army would have in both joint operations with Allied forces, as well as a way to validate training of their own troops. Coughlin, like his American counterpart Bill Mauldin, participated in the invasion of Sicily, and then went to work drawing the famous characters while initially in Naples. While many of the cartoons became icons of their particular fighting men, it is Herbie more than any other that was the “face” of the Canadian fighting man.

Herbie was well meaning but often the epitome of what NOT to do in combat, whether trying to drive between a bulldozer and a tank with his jeep, or drinking the local vino while in Italy, or simply complaining of the things that all soldiers did: a lack of women, decent food, and mostly the desire to go home. However, he was not a shirker and he did his job well. The sense of humour shown by Herbie was typical of combat jokes. He was an expert on different types of soil after digging so many trenches or foxholes. At times he had visions of personal glory, but more often was quick to head for shelter and safety. Mostly, he simply wanted to get the job done and get back home to his regular life. Coughlin drew his cartoons with an eye on the average grunt. As with so many military historians, the life of the enlisted man is frequently overlooked, in favour of the battle or the commander. However, by looking at the cartoons, which were meant for the common soldier, one can tell of morale, of equipment comparisons, or even the condition of fighting.

Coughlin was quick to pick up on emotional themes from the Italian campaign. The gripes about constant digging of trenches were similar to the cartoons from American artist Bill Mauldin as were the cartoons of stolen or stripped jeeps. Other cartoons were uniquely Canadian: one was a cartoon of a sniper engaged in his deadly craft, with his spotter noting, “Whatever you do, don’t hit his binoculars!” No doubt this was in reference to the Zeiss binoculars prized by the Allies for their superior optics.

Several other cartoons made light of Herbie’s run-ins with the military police while on a temporary pass, or even of the MPs grabbing German prisoners of war. One cartoon noted that the MPs were in such a rush to put up the out-of-bounds signs that they advanced too far and were in fact now prisoners of the Germans. Many of the German POWs were quick to point out to Herbie and his comrades that they would be in Canada before the Canadian troops would.

Beanie was a character that Coughlin later introduced to work and pal around with Herbie. Like Willie and Joe of American fame, they would run afoul of military police, drink lots of alcohol, enjoy the sights, and think about home. Herbie later would be depicted by Coughlin in the process of slowly making his way back to Canada and the various troubles or escapades he encountered on the way back. Regardless of how, the key was that they were home. W

Next month: D-Day and the cartoons of Festung Europa will be profiled