(Volume 24-09)

By Jon Guttman

Resentment over the failure of the government to live up to their treaty obligations, the Cree rose in armed revolt. The Canadian military response was relentless in its pursuit of the perpetrators.

Although neither as epic nor bloody as the Civil War and the numerous, widespread Indian Wars fought in the United States throughout the 18th century, Canada’s North-West Rebellion of 1885 encapsulated many elements of those tragedies attending its southern neighbour’s westward development. Both nations’ conflicts involved issues of government, nationality, citizenship and justice, as well as the less abstract matter of land ownership.

Even while fighting each other, both Union and Confederate soldiers occasionally had to deal with hostile Native Americans on their frontiers. Likewise, while the Canadian Army fought the Métis, it also had to detach two columns to subdue restive First Nations. As a final parallel touch, on May 10, 1869, the United States completed its first transcontinental railroad and on November 7, 1885, Canada did the same — its progress largely accelerated by the requirements of war.

The North-West Rebellion began on March 19, 1885, when Métis leader Louis David Riel established the Provisional Government of Saskatchewan, after which an attempt was made by North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) and Prince Albert Volunteers under Superintendent Leif Crozier to arrest him on March 26th, only to be routed at Duck Lake, 2.5 kilometres from Riel’s self-proclaimed capital of Batoche. While the Métis were fighting for their land and their way of life, however, the region’s First Nations had more existential grievances. A decline in the bison population, combined with lapses in the government’s distribution of rations in accordance with its own Treaty 6 caused widespread hunger that drove many tribes to request renegotiation. Although there is no evidence of a direct alliance between the Métis and the First Nations, influential spokesmen such as the Blackfoot chief, Crowfoot, averted violence among most of the Aboriginals. However, two small bands, largely encouraged by word of the recent Métis success at Duck Lake, became involved in their own concurrent private wars with Ottawa.

On March 30, a band of Cree led by Poundmaker (Pîhtokahânapiwyin) tried to speak to John M. Rae, the Indian agent at Battleford, but were put off for two days. In consequence, some of Poundmaker’s starving people began looting abandoned homes in the area. While the Cree milled about Fort Battleford, Assiniboine warriors from the Eagle Hills, moving to join Poundmaker, killed two farmers along the way, adding to the frightened white residents’ perception that they were under siege.

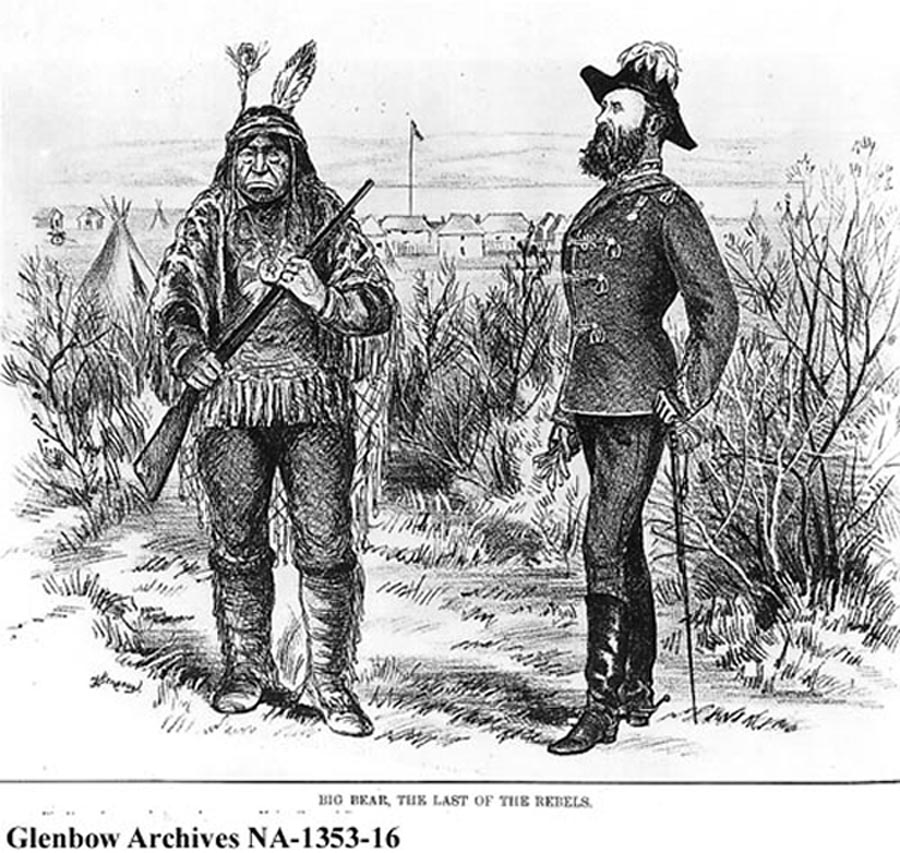

Hunger and resentment led to an even greater tragedy at Frog Lake in what is now Alberta. There, some 250 Wood Cree nominally led by Big Bear (Mistahimaskwa) camped outside of the Hudson’s Bay Company post on April 2. Big Bear was an old and respected statesman, not least for his refusal to sign Treaty 6, but when his people were forced to settle in reserves anyway, his authority began to decline. Although Big Bear tried to moderate the younger, more volatile braves, the real power in his band was shared by his son, Little Bear (Ayimisis) and his war chief and shaman, Wandering Spirit (Kapapamahchakwew).

The focus of their resentment was Indian agent Thomas Trueman Quinn, who had long denied them rations with harshness and arrogance. Just before 1100 hours, the Cree ordered all of Frog Lake’s residents to their encampment two kilometres away. When Quinn flatly refused to leave, Wandering Spirit shot him in the head. This touched off several minutes of panic and frenzy marked by more shooting by the Cree, resulting in the deaths of sawmill operator John Gowanlock, farming instructor John Delaney, clerk William Gilchrist, trader George Dill, carpenter Charles Gouin, Catholic priests Félix Marchand and Léon Fafard, and Fafard’s lay assistant, John Williscroft. A tenth man present, Hudson’s Bay clerk William Bleasdell Cameron, survived only because Cree women hid him under a large shawl until the braves’ rancour cooled down. He and widows Theresa Delaney and Theresa Gowanlock were then rounded up with other locals, totalling 70, and forced to accompany the war band as captives. The agent’s nephew, Henry Quinn, managed to escape and report what had transpired.

On April 13, Big Bear’s band surrounded Fort Pitt and issued an ultimatum for its North-West Mounted Police to surrender. Big Bear, however, separately contacted an old friend there, Hudson’s Bay Company trader W.H. McLean, assuring him that his people’s fight was only with the “government people” and advised him to put all civilians under his protection. The next day the 26 NWMP (including Inspector Francis Dickens, son of author Charles Dickens) escaped, save for one man killed, one wounded and one captured. Although the Cree ransacked the fort, true to Big Bear’s word they left the civilians unmolested.

Meanwhile, retribution was on the way as Prime Minister John A. McDonald’s government dispatched a North-West Field Force to deal with the Métis rebellion. Alternately riding on the Canadian Pacific Railroad and marching along the uncompleted stretches, the army divided three ways upon arrival in Saskatchewan. While the main force of 900 soldiers and militia, led by MGen Frederick Dobson Middleton, departed Fort Qu’Appelle for Batoche on April 10, a separate column under LCol William D. Otter left Swift Current on the 13th to relieve Fort Battleford and a third column of more than 500 troops and NWMP under MGen Thomas B. Strange left Calgary for Edmonton, charged with bringing Big Bear to ground.

Otter reached Fort Battleford on the 24th, only to find Poundmaker’s combined band of Cree and Assiniboine long gone — they had retired to his reserve at Cut Knife Creek, 40 kilometres to the west. Angry locals pressed Otter to chastise the Indians for their looting spree and although General Middleton had ordered him to stay in Battleford, he obtained telegraphed authorization from Edgar Dewdney, lieutenant-governor of the North-West Territory, to “punish Poundmaker.” On May 2, the Canadians reached the Cree reserve and attacked, but the 50 braves who opposed them, operating in four to five man squads under the direction of Poundmaker’s war chief, Fine Day (Kamiokisihwew), inflicted stinging casualties and were threatening to outflank the soldiers when Otter, recalling the fate of U.S. Army LCol George A. Custer at the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876, ordered a withdrawal. The Battle of Cut Knife Hill was the greatest First Nations victory of the war, but everyone involved knew it would not affect its ultimate outcome. After the fall of Batoche and the capture of Louis Riel on May 15, Poundmaker and his starving tribesmen began giving themselves up. By the end of the month, only Big Bear and his Cree remained at large.

The man on their trail, Thomas Bland Strange, had been born in Meerut, India, on September 15, 1831. A veteran of the 1857 Indian Mutiny, he later became a founding officer of the Canadian Army and particularly of its artillery, where he earned the nickname of “Gunner Jingo.” By 1885, he had retired to Calgary to raise cavalry horses, but when war broke out an old friend, Minister of Militia and Defence Adolphe-Philippe Caron, cajoled him out of retirement to organize a field force in Alberta. He did so, though most of his 375 infantrymen and 100 mounted ranch hands were woefully inexperienced. Fortunately for Strange, his three Assiniboine scouts and 25 Mounted Police were not, especially their commander, Inspector Samuel Benfield Steele, a founding member and already a legend of the NWMP. When Strange summoned him in early April, Steele was feverishly ill and otherwise engaged, dealing with 1,200 unpaid railroad workers threatening to strike. At one point facing down some 700 angry workers and reading them the riot act, Steele managed to defuse the situation and maintain peace until April 7, when — largely through his own pleas to the Canadian Pacific — the workers’ long-overdue pay finally arrived. Soon afterward, he joined Strange at Calgary. Strange ordered the NWMP to affect cowboy dress, claiming that their conspicuous red uniforms made his eyes ache. He made a unique exception of Steele, who he said, “could not give up the swagger of his scarlet tunic, and I did not ask him to make the sacrifice.”

On May 25, Strange’s column reached Fort Pitt, which the Cree had burned before retiring into the nearby hills. Strange’s pursuit was punctuated by minor skirmishes until the night of the 27th, when his troops reached Frenchman’s Butte. On the hill east of it, Wandering Spirit ordered his warriors to dig trenches and rifle pits.

The next morning, Wandering Spirit selected 200 braves to man the defences, while the rest, under Little Poplar, guarded the women and children two miles to the east. Strange advanced on their position at 6 a.m. and opened fire with his cannon, to which the Cree replied with a fusillade. As the Canadian troops advanced, however, they discovered the valley to be a morass of muskeg, followed by a stretch of open hillside rendering a frontal assault suicidal. Strange pulled them back and redeployed them with the RCMP on the left flank, the 65th Battalion, Mount Royal Rifles and Winnipeg Light Infantry Battalion in the centre and the Alberta Mounted Rifles on the right.

Strange then ordered Steele and his Mounties to ride along the creek on the Crees’ right, find a crossing and flank them. Wandering Spirit, however, took four or five men and led them along the wooded ridge, firing on the NWMP whenever they tried to cross the creek. After a mile and a half of trying, Steele pulled back, reporting hundreds of Aboriginals along the ridge — thoroughly deceived by the actual number he’d faced.

Meanwhile, other Cree managed to get around the Alberta Mounted Rifles and almost overran the supply train. At that point, three hours into the engagement, Strange, like Otter at Cut Knife Hill, expressed concern of “committing Custer” and retreated back to Fort Pitt. Frenchman’s Butte was a virtually bloodless victory for the Cree, but it only bought them a short reprieve from pursuit by Steele’s relentless Mounties and mounted militia he’d formed called Steele’s Scouts. In an encounter on May 29, Steele’s Scouts exchanged fire with some Cree and killed one of them, Mamenook.

On June 3, General Middleton arrived at Fort Pitt with 200 troops and assumed command of Strange’s column. Meanwhile, Big Bear’s band had withdrawn into the swampy wilderness to the northeast, hoping the terrain would discourage the Canadians, but Steele, leading 47 NWMP, Steele’s Scouts and Alberta Mounted Rifles, remained determined to “get his man” (or in this case, men). He caught up with 150 of them at Loon Lake. Though low on ammunition, the warriors made a spirited stand, wounding seven men, including Steele’s long-time deputy, Sergeant Billy Fury. Anywhere from four to 12 Cree were killed and dozens wounded, before they disengaged and withdrew into the woods, their ammunition all but spent. Loon Lake, since renamed Steele Narrows, was the last battle fought on Canadian soil.

With their position clearly hopeless, the Cree released some captives on June 18, with a message entreating “our Great Mother, the Queen, to stop the Government soldiers and Red Coats from shooting us.” Soon thereafter, they turned themselves in, along with their remaining captives, at Fort Pitt. A notable exception was Big Bear, who, with his 12-year-old youngest son, Horse Child, somehow slipped through the NWMP cordon and walked 100 miles to Fort Carleton, 100 miles to the east, before surrendering to a surprised sergeant on July 2.

The North-West Rebellion was over, save for the retribution. In the trial that followed in Regina, Wandering Spirit, Little Bear, Round the Sky, Bad Arrow, Miserable Man and Iron Body were sentenced to death for their part in the Frog Lake Massacre. They and two other Cree warriors convicted of murder were hanged in Battleford on November 27, the largest mass execution in Canadian history. Big Bear was spared their fate, largely through William Cameron’s testimony that he had opposed the shootings and had saved his life. However, in spite of Henry Ross Halpin’s testimony that he considered Big Bear as much a captive of the warrior band as he had been, the old chief was convicted of treason on September 11 and presiding judge Hugh Richardson sentenced him and Poundmaker to three years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary. Released due to failing health in February 1887, Big Bear spent his last days with his daughter at the Little Pine reserve until his death January 17, 1888, aged 62. Having been baptized while in prison, his remains were buried in the reserve’s Catholic cemetery.