(Volume 24-02)

By David Pugliese

As the twentieth century dawned Currie’s life was at its nadir. Teaching seemed to offer only a life of gentile poverty. He had no economic prospects to speak of, a limited network and a stalled militia career. Illness, an affliction in and of itself, had forced him to sit out the South African campaign and his militia career was largely undistinguished.

However, in the spring of 1900 Currie’s joining Matson and Coles, the prominent Victoria insurance firm, triggered a remarkable change in his fortunes. Turns out he was successful as an insurance salesman and his income increased considerably and quickly as a result. Insurance company co-owner JSH Matson, despite being only half a dozen years older than Currie, quickly developed into a friend and mentor. Four years later, when Matson became the publisher of Victoria’s Daily Colonist, Currie took over as manager of Matson and Coles. In 1906, he also became provincial manager of National Life Assurance of Canada. Currie’s advancement within the industry speaks to his ability to master a new set of skills and stands as evidence of growing prosperity.

In 1908 he struck out in a new direction when he established Currie and Power, a real estate firm. Apparently, success in insurance sales allowed him to accumulate the capital to take this step. At the time, real estate was not sold by agents for a commission; the owner, developer, promoter and salesperson were one and the same. Currie and Power speculated in land. They relied on subdivision, development and sales, enhanced by the inflationary pressure of a hot real estate market, for profits. The considerable capital required demonstrates that Currie was getting ahead financially.

A friend, Augustus Brindle, describes an office with map-covered walls supplementing Currie’s pitch highlighting the specific features of each lot and parcel of land. The Victoria economy was booming, and the city regarded itself as “the best-paved, best-lighted and best boulevarded city in North America.” A lot in Fairfield, a new suburb, bought for $400 in 1908 could be sold for $5,000 four years later. Colonel Hugh Urquhart, historian for the 16th Battalion (The Canadian Scottish), asserts that Currie netted over $17,000 on property sales in 1911. A history of the province published in 1914 described Currie as owning “much property in Victoria and surrounding area” while operating from “commodious office premises on Douglas Street,” in the Vernon Hotel.

Socially, Currie’s profile and influence grew with his new-found financial success. On August 14, 1901 he married Lillian Warner (née Lucy Sophia Musters). The nuptials were a highlight of the Victoria summer and garnered significant coverage in the social pages. The Colonist described the bride’s gown as a “handsome costume of cream satin, with veil.” Dispensing with specifics, the Daily Times simply noted she was “extremely pretty.” To a friend, Currie confided he had presented his bride with “a handsome ring set with diamonds and opals.” Over the next decade, the couple would have three children: Marjorie (1902), Garner (1911), and a child between them who died in infancy.

Affluent and with an established home, Currie’s community profile was growing. A gifted marksman, he joined the British Columbia Rifle Association, quickly assuming the presidency, a position he held until the outbreak of war in 1914. It was in this role that he first encountered Sam Hughes. A politician and publisher, Hughes was a fanatical proponent of the militia and saw the citizen-soldier as the ideal warrior. An organization promoting martial arts among the citizenry earned both his support in Parliament and his active participation as a member of the national executive. Through the militia, Currie became friends with Hughes’s son, Garnet, a fellow militia officer four years his junior.

Currie was also active in the Orange Lodge, rising to Deputy Grand Master of the Victoria District of Freemasonry in 1907. Politically, he was a lifelong Liberal and spent two years as president of the Young Men’s Liberal Association of Victoria. By 1911, his public profile was such that he garnered an entry in Who’s Who in Western Canada. Along with being senior partner in Currie and Power, it noted he was president of both the King Edward Mine and the British Columbia Rifle Association. Currie was also vice-president of the Artillery Association and a member of the Pacific Club.

Prior to 1900, Currie’s militia career was largely undistinguished. On June 5, 1897 he had been taken onto the strength of the 5th Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery, dubbed the ‘Dandy Fifth’, as a gunner. He received only one promotion. In the winter of 1897–98, he earned his first stripe and was appointed company secretary.

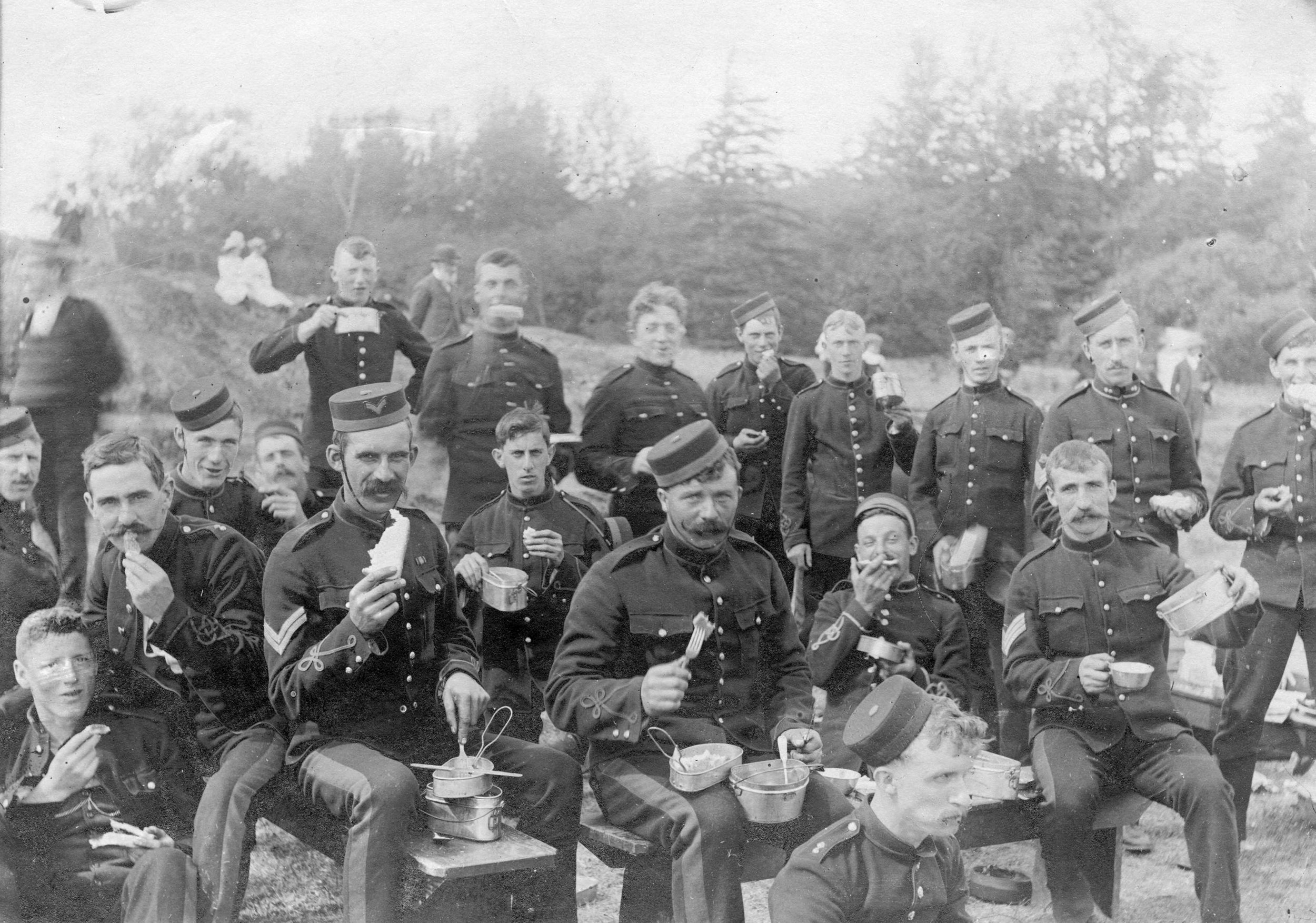

While the Canadian government loved the idea of the citizen-soldier militiaman, it adored even more his low price. Throughout the 1890s the Canadian militia reeled in the face of budget cuts. In 1895, all rural training had been cancelled indefinitely and the income of urban regiments was reduced by one third. Cost, to the public purse, competed with the ideal of competence. The Victoria-based 5th Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery, while models of sartorial splendour, were still training on ancient muzzle loaders that they would never fire in anger. Ultimately, in the pithy words of historian Frank Underhill, the militia were “not taken seriously by the country at large and hardly by itself.”

They were ill-equipped and undertrained at the very time that the pace of technological change was accelerating and revolutionizing the art of warfare. Historian James Wood describes the militia as “a social rather than a military occupation” and notes that their “martial enthusiasm far outstripped their expertise.” Consequently, the primacy of military competence was also neglected in terms of promotion. Patronage and personal wealth played a larger role in advancement in the militia than martial proficiency. As a lowly high school teacher, Currie could neither socially earn nor financially afford promotion.

However, his militia career took off as soon as he entered into business, in large part a reflection of his increased income and influence. Less than a year after his illness, he skipped the rank of sergeant and was gazetted a 2nd lieutenant. Eleven months later, he was promoted to captain, and appointed CO of No. 1 Company. Subsequently, in seven of the eight years he was CO, the company won the Regiment Efficiency Shield. In two years, he advanced from the ranks to captain. In May 1906, Currie was promoted to major and became second in command of the regiment. He became the Dandy Fifth’s CO on September 1, 1909 along with promotion to lieutenant-colonel. Again his unit excelled: In four of his five years as CO they won the Governor General’s Cup as well as three Landsdowne Cups and two Turnbull Shields.

His units’ achievements testify to Currie’s skills as a militia trainer: As a militia officer he also remained a star pupil. As a lowly subaltern he averaged 96 per cent in examinations. He earned a First Class, Grade A badge from the Royal School of Artillery. In early 1914, he achieved the highest grade in a course on the Franco-Prussian War conducted by Major Louis Lipsett. Historian Tim Cook describes him as “perpetually devoted to soldiering,” and Currie once confessed, “When some of my associates were playing lawn tennis or swinging golf clubs, I was at the armouries or on the rifle ranges with the boys.” In the 1900s the Canadian militia was no potent military force, yet Currie was one of the best of a lacklustre lot.

While Currie had no combat experience when he arrived in Flanders in 1915, he had led a military operation, and done so with intelligence, effectiveness and flare. From 1912 on, strikes and union drives persisted across Vancouver Island’s coal mines. In August 1913 a labour dispute between coal miners and mine owners in Nanaimo, north of Victoria, became increasingly violent. The Chinese miners were seeking a first contract as members of the United Mineworkers of America. Canadian Colliers (Dunsmuir) Ltd responded by locking them out and bringing in scabs. On August 12, after violent disturbances and erroneous reports of as many as six deaths, the Attorney General of British Columbia, William Bowser, ordered out the 88th Victoria Fusiliers and Currie’s Dandy Fifth.

Commander of the Victoria Fusiliers, Currie’s predecessor as CO of the 5th, Colonel John Hall, was in command of the operation, but he fully acknowledged Currie handled the deployment, exhibiting “wonderfully accurate powers of sizing up the situation.” A detachment of special police arriving by boat had previously been beaten off by a mob on the docks. Currie determined that the docks had been neutralized and that even an alternative approach would require an accompanying diversion.

Thus while Currie’s main force did travel by boat, it landed at Departure Bay, five kilometres north or seaward of Nanaimo. While the miners concentrated south of Nanaimo, preparing to confront a small, but very public diversionary force en route by train, the main force was able to secure Nanaimo. While the constitutionality of the Attorney General’s deployment of the militia has been questioned, its efficacy cannot be. Currie attained his objective by occupying and pacifying Nanaimo while using both manoeuvrability and misdirection to avoid violence. Conceived with flare and executed flawlessly, Currie’s performance did not go unnoticed.

In the wake of the Nanaimo strike operation, Currie was preparing to wrap up his militia career and retire as CO of the Dandy Fifth, but a ghost from Currie’s heritage, ethnic chauvinism, was about to intrude. The Victoria Fusiliers were the preserve of Victoria’s English elite. Since its appearance in late 1912, the city’s Scottish merchant class had been hollering for a Highland regiment of their own. On August 24, 1913 the federal government authorized the 50th Regiment (Gordon Highlanders) and the search for a commanding officer commenced.

Currie, whose militia experience the Daily Colonist described as “second to none in the province,” was soon being touted as a potential CO of the new regiment. He prevaricated. Unbeknownst to his boosters, Currie was preoccupied with a personal financial crisis. The building boom that Currie had ridden on an inflationary wave to affluence and influence had crested. The market dried up and when buyers disappeared, Currie’s heavily mortgaged properties quickly became liabilities. Currie, accustomed to overseeing vigorous sales and growing profits, was suddenly struggling to avoid insolvency. In his current financial straits, Currie could not afford to assume command of the 50th. Arguably, his time and energies were also better directed to redeeming his precarious personal finances. He only agreed to take over the regiment when a financial saviour agreed to underwrite the regiment in return for the honorary lieutenant-colonelcy.

His friend and now the regiment’s second-in-command, Garnet Hughes, was influential in persuading Currie to accept the position. Six months later, Garnet played a key role in the back and forth between Currie and his father that saw Currie placed in command of the Second Brigade at Valcartier in August 1914. Lieutenant-Colonel Arthur William Currie, ages 38, suspended over a financial abyss and months earlier on the verge of retirement from the militia, was on his way to war.

Currie was embarrassingly unassuming in appearance and bearing. Early in his militia career he actually hired a fitness instructor to improve his posture. A great bear of a man, he stood almost two metres tall. Unfortunately, his Sam Brown belt rode up over a substantial belly that, along with an ample bottom made the more unseemly in jodhpurs, had him forever appearing like a uniformed Michelin Man. A soft chin, fleshy mouth, and bare upper lip did little to create a martial mien.

Appearances are deceiving and the things this southern Ontario farm boy with the 3rd class teaching certificate carried with him, were about to blossom. In three years he would be commander of the Canadian Corps, indisputably the most potent fighting force to take the field in the First World War; he was regarded as one of the best, if not the best, general in the British forces; and he was reputed to be in line to become the next, and first colonial, British Army commander if the war went on into 1919.