(Volume 24-01)

By Cord A. Scott

Last month, we learned how the venerable comic panel became a much-utilized creative outlet for Canadian soldiers during the Second World War. Several Canadians — Bing Coughlin, H. Stewart Cameron, David Low and Les Callan among them — became well-known war cartoonists after their drawings were published in enlisted men’s newspapers. The second part of “Herbie to the Front” concludes with a study of Les Callan’s iconic Johnny Canuck.

D-Day and the cartoons of Festung Europa

The cartoons that portrayed the fighting of the Canadian Army were often as varied as the conditions themselves. While one doesn’t necessarily get the impression of the difficult, mountainous conditions of Italy from the Herbie cartoons, one does begin to see how the two theatres were different in their fighting styles. For many of the cartoons done in northwest Europe (Normandy, Belgium, into Holland and Germany), the mobility of units and the fluid situation of the fighting was far more prevalent. In addition, there were more cartoonists brought in to tell the “humour” of war.

One artist who drew of the build-up and invasion of France was Lt. Les Callan, who created a strip entitled Monty and Johnny for the Maple Leaf Northwest Europe edition in the fall of 1944-1945. Callan started off in the Army Reserve in 1940, went into the Artillery in 1942, and then was assigned to the army Public Relations Branch, where he drew cartoons for the Maple Leaf. One of Callan’s earliest cartoons on the invasion was the fact that the supplies for France were so heavy it was tilting the entire island of England. As the troops awaited the invasion, spirits ran high, and ran through the men, as many local pubs sold out of spirits. Another of Callan’s jokes in the cartoons was the fact that Johnny Canuck was constantly misreading French and was trying to impress his friends and fellow soldiers. In 1945, after the end of the war, Callan published his cartoons in a book entitled Normandy and On: From D-Day to Victory. In it, he went one step further and added realistic illustrations of real soldiers as a kind of greeting card back home, such as L/Cpl. George Laverock from C Company of the Canadian Scottish Regiment, who hailed from Frae Auld Victoria.

As the Canadians progressed inland, the cartoons noted the lack of “Superman” in the German army. One cartoon noted that the Germans should be thrown back as they were under the limit. Perhaps Callan’s most humorous cartoons dealt with the dispatch riders, who seemed to go everywhere and through even the most inhospitable conditions and traffic to get where he needed to be. In one cartoon, based on an actual event, a dispatch rider even came in with a group of German prisoners of war. While he was riding he made them jog, stating “There’s nothing in the Geneva Convention which says you can’t run so git going – yuh Baskets!”

There were some issues of internal censorship. Since the cartoons were produced for as wide an audience as possible, overtly crude language and blatant sexual references were avoided for publication. However, the women drawn were often drawn in a pinup fashion, with physical attributes that made them seductive to the eye, and suggestive in their occupations. All in all however, the language and sexuality were often unstated, and the violence more for comedic effect. Of all the cartoons perused by the author, only two have ever shown dead soldiers, and the cartoons were American. The two in question were from Hubert, by Dick Wingert, which ran in the U.S. Army paper Stars and Stripes. One referenced the smell of dead bodies, and the other featured Germans who died in holding a town. Both were examples of gallows humour.

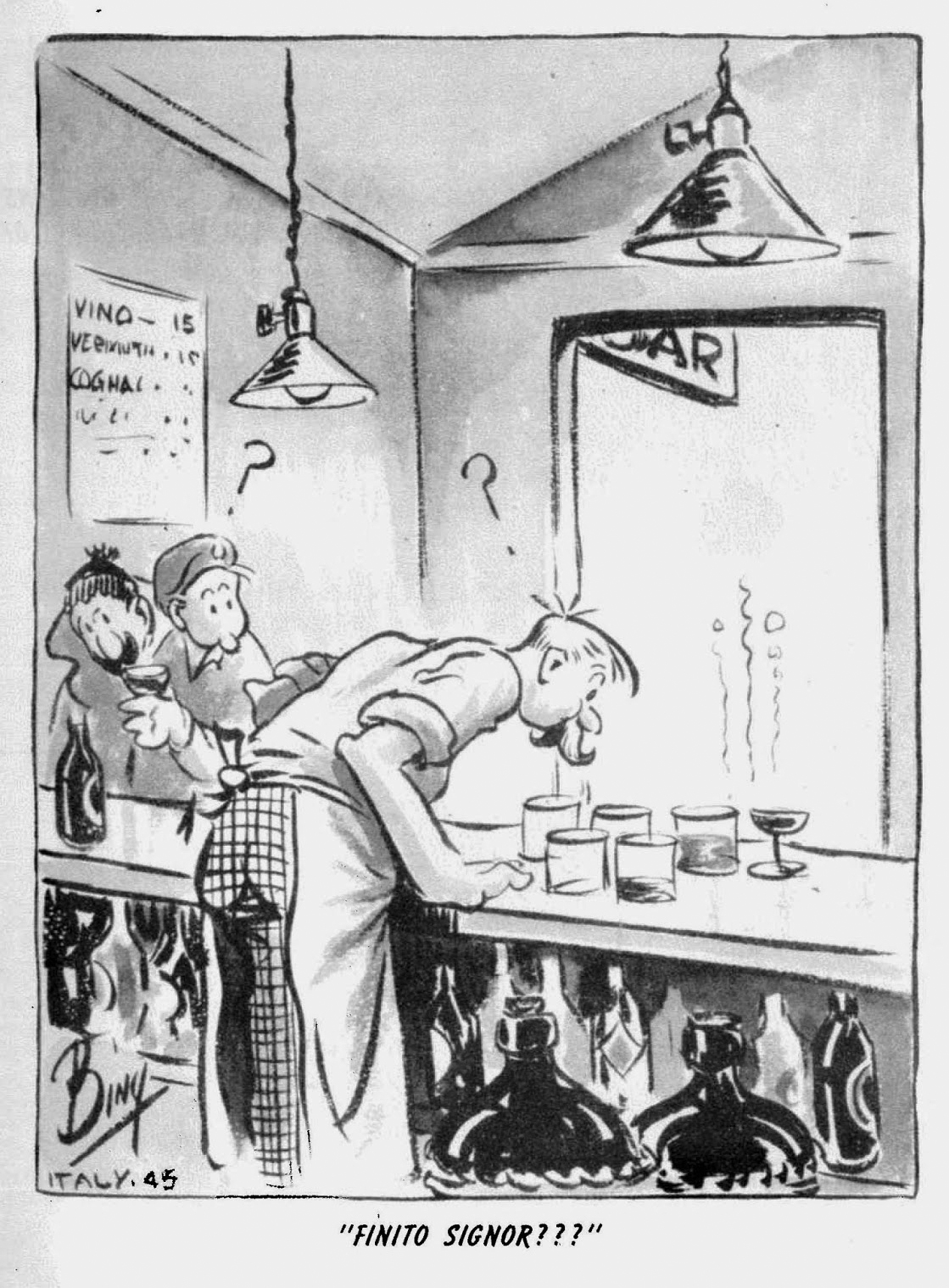

For the artists in the northwest theatre, be it Callan, Tom Luzny, Jan Nieuwenhuys, or L. Clay’s illustrations in the 13th Field Regiment of the Royal Canadian Artillery, the cartoons reflected the conditions of the soldiers in the field. As the Canadians moved from Normandy, through Belgium and into Holland, the stories often told of how they adapted to the local conditions. All of the cartoonists noted the search for some sort of alcohol, be it Calvados from Normandy, or beer, or something stronger in Holland. Other cartoons noted the “accidental” discharge of weapons or artillery that happened to kill local animals. Since they couldn’t go to waste it was best to cook them, especially with the field kitchen nearby.

This was not to say that others didn’t contribute to the war effort or to the cartoons. Les Weekes was another cartoonist who drew for the Maple Leaf, with the title of This Weekes’ War. One of his notable cartoons, republished in Maple Leaf Scrapbook, was one in which a recce jeep had crashed into the water, and upon inspecting the map (underwater) the officer noted, “Hey, you know that canal bridge? Well it’s gone!”

Nieuwenhuys did a small book for the Canadians stationed in Holland during the winter of 1944-1945. Entitled Daag, the booklet featured sixteen comic-like colour caricatures of life in Holland. These illustrations were not of combat but of rest and recuperation in the area. Many of the cartoons dealt with the bartering of cigarettes for alcohol or even female companionship. Another discussed that “d-d Dutch Gin.” And finally several cartoons dealt with driving around the small country in oversized Allied army vehicles that often clogged the roads.

Clay’s illustrations that accompanied the history of the Royal Canadian Artillery were humorous but also told of more pressing issues. After the early comics that illustrated the training conditions, the later cartoons exemplified the conditions of the army in Normandy. Early on it was easy for the artillery to target anything that moved in Normandy. One cartoon, the appropriately named “Enemy Movement,” noted that the forward observers were calling in a strike against a German answering the call of nature. Another cartoon again went back to the “tradition” of making use of cows that were killed after being mistaken for enemy troops or being collateral damage from some sort of strike. Since the animals would rot otherwise, why not use them to augment the regimental kitchens, “Rations Supplement” suggests?

However, as the unit moved further into Holland during the fall of 1944, the fighting was more intense, leading to the jokes of bunkers (in Clay’s “Command post Fashions”), as Herbie had lived in Italy, or the sudden need to conserve rounds, as was common during the later part of the winter when supplies were hindered from reaching the front. One Clay cartoon titled “Ammo Return” even went so far as to note that a young lieutenant was about to hang himself for not reporting the proper count of artillery shells.

The key to many of the Canadian military cartoons is that they serve as a type of visual record of the fighting in Europe. While there were some artists and cartoons that were meant to be universal, such as the complaints about ineffective officers, training regimens, or food and drink, many of the cartoons did serve as a reminder of local issues encountered during combat. It might be Italian women or the incessant mud of Italy, the Calvados and Canadian troops trying out their French language skills on the locals, or the Dutch weather in the fall, but regardless it was important for soldiers to retain those memories. Callan often used many true stories as the basis for the cartoons, as did many cartoonists from all countries. Of all the cartoonists and their creations however, Coughlin’s illustrations of Herbie are the most memorable and universal.