(Volume 24-03)

By Robert Smol

In late March of 1917, as the artillery phase of the Battle of Vimy Ridge was ramping up, a new inexperienced siege battery was getting ready to fight.

It was here, in a muddy swamp, that history was made for Canada and McGill University. In the line-up for the first major battle fought by a unified Canadian Corps was a combat unit recruited from and bearing the crest of the university.

The 7th Canadian (McGill) Siege Battery was barely a year old when it slogged and staggered into the line at Vimy. At the time, it was commanded by a university professor and manned mostly by students from McGill and its subsidiary MacDonald College.

At almost every turn, fate frowned derisively on this new unit. They had little time to prepare, having arrived late. Facing bad weather, they were also desperately short of food and supplies. To worsen matters, the unit’s commanding officer seemed headed for a mental breakdown. But they managed to pull through. And when zero hour came at 0530 on April 9, the McGill Battery was ready.

The 7th Canadian Siege Battery was one of five units mobilized and trained at McGill for overseas service and it was the first combat unit from the university to deploy overseas. The 7th even managed to retain its original university identity with McGill’s crest being emblazoned on the unit’s badge. Its affiliation was not lost once deployed overseas.

Slogans for recruitment, such as “Calling on men of trained intelligence” and “For God, for Country, for McGill” brought in the initial intake of recruits in the spring of 1916. Initially, the Majillses, as they were popularly called, were designated the 6th and the 271st, until receiving the designation 7th.

The battery’s first commanding officer was Major William Dunlop Tait, a professor at McGill. He served in the Corps of Guides before the war. After the war in 1924, he founded the department of psychology at the university. A professor of English, Captain Cyrus MacMillan became the deputy commander of the unit. He was also an author.

According to Gunner Terence Macdermot’s memoir The Seventh, written in 1953, the battery initially consisted of 61 active students as well as 35 clerks, eight engineers, two architects, and six teachers — many of them McGill alumni. The unit also had a gardener, barber and farmer.

After conducting training in Montreal, Halifax, and Great Britain, the 7th was ordered to proceed to the Vimy front. Landing at Boulogne, France on March 15, 1917, the unit departed in motor lorries for the front on March 27.

On the unit’s journey to the front, tractors dragged the guns, slowing the trip as they had to make frequent stops, wrote Gunner Richard Beverly Moysey in his diary. For the next two days, the battery slept in farmers’ barns, dealt with frequent delays, choked roads, worsening weather and mechanical breakdowns. Moysey could hear the distinct sound of gunfire and spent his evenings “watching the illumination along the front.”

Once arrived at the front, the unit was greeted with a tactical and logistical nightmare. The unit was ordered to place their howitzers — short guns firing shells on high trajectories at low velocities — in a swamp.

A frustrated Captain Cyrus MacMillan wrote of the muddy conditions in his personal diary. “Did our best to get things in order. Living in a swamp. No material to work with. This is Canada’s treatment of us!”

The unit’s official war diary was equally ominous in its assessment of the situation and the challenge of getting guns positioned and calibrated on time.

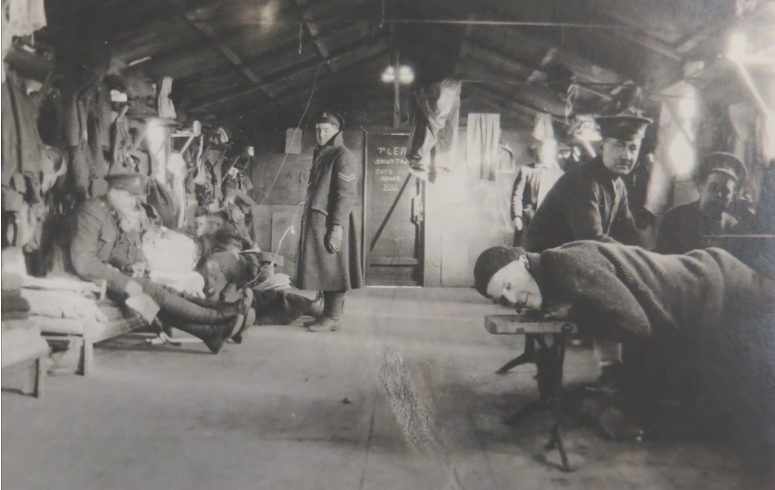

“No material to work with, no brick, stone, or timber. Men sleeping in mud and water or under canvas. Rations very poor.”

According to Gunner Macdermot, the supply situation worsened so much that “the hungry gunner was not above picking a stray onion from the mud, wiping it on his muddy sleeve and swallowing it, mud and all.”

The first two guns arrived at 2300 on April 2. Without proper supplies to mount the guns, the men began to scrounge through the ruins of a local village to get whatever material they could improvise with.

Hauled into position by the wet, hungry and sleep-deprived gunners at 0200 in the morning, they were greeted by a torrent of rain and snow. The remaining two guns arrived the following midnight and were hauled into their improvised gun pits. But before they could move on in their preparation, a gun had sunk in the mud.

The McGill gunners tried unsuccessfully to pull it out, only to see it sink once more. Two tractors attempted the feat, without any luck. Anxiously, they began to implement their programme of preparatory firing to ensure that the guns were properly calibrated and the improvised platforms and gun pits were secure enough to withstand a continuous and heavy gunfire. Over the remaining two days, the unit fired over 200 shells to ensure that their guns and designated targets were properly calibrated and registered.

Added to the litany of challenges was a missing commanding officer. Almost immediately after the unit’s arrival at Vimy, Major Tait confined himself to his tent and remained shut off from any interaction with his unit or with medical personnel for five days. Interestingly, the professor who founded McGill’s psychology department was likely suffering from a mental health crisis at Vimy.

Although Tait’s condition was not mentioned in the unit’s official diary, Captain MacMillan included “Major still in bed” for each of his diary entries from April 1 to 4. In a private letter to his brother, MacMillan was more detailed. “He did not appear sick — and his indisposition, I fear, gave a strange impression.” On April 5, Tait reported to the hospital, making deputy commander MacMillan the leader of McGill’s first combat unit.

Though MacMillan doubted their CO’s return, Tait did return after Vimy, commanding the unit during the Battle of Hill 70 in August 1917.

The world “seemed to thunder,” recalled MacMillan, when the guns began their bombardment of Vimy Ridge on April 9. In addition to destroying Vimy Ridge, the 7th McGill Siege Battery was focused on destroying the villages of Thelus, Farbus, and Farbus Wood, as well as the roads leading to Thelus. During the first day of the battle, the heavy guns, firing from the dreadful swamp, had expended 350 rounds.

“We fired as hard as possible until noon,” recounted Moysey in his diary. After that, the gunners were on standby, ready to respond to SOS calls from the infantry, while it was consolidating its position on the ridge. “The German prisoners started coming back,” wrote Moysey. “Some of the boys went out and got their helmets in exchange for cigarettes.”

The same throng of German prisoners that weaved through the lines of the 7th all morning were described by MacMillan as tired-looking young men, with “pale unshaven faces, tanned about the eyes.” As they passed MacMillan and the others, “they placed their hands over their ears as if to shut out a noise that would have brought memories of hell.”

After Vimy, the 7th went on to fight at Lens and Hill 70, Passchendaele, Arras, Canal-Du-Nord, Valenciennes, and Mons. There is nothing to remind today’s McGill students of their First World War unit, aside from a discrete plaque placed on campus by veterans of the battery after the war.