When Brian Mersereau, Chairman of Hill & Knowlton, wrote for Defence Watch about the Canadian Surface Combatant (CSC) program on September 12, 2014, he buried a bread crumb under a heap of neatly written paragraphs.

As the most expensive and complex naval procurement in Canada’s history, the government is under a lot of pressure to get the CSC program right … mostly because they so often get major defence acquisition programs wrong. The Canadian Armed Forces must grit their teeth at the bureaucratic ineptitude that forced them to saunter up to the National Air Force Museum in Trenton, cap in hand, to ask for parts for their half-century-old CC-130 Hercules aircraft.

An RCAF CC-130 Hercules

At this point, however, those teeth must be worn down to the gum line. While successive governments fail to deliver promised equipment to the military, the guys and gals on the front line somehow manage to keep aircraft in the air, ships at sea, and vehicles on the road decades longer than their predicted life spans. It’s like travelling the streets of Havana and marvelling at all those old Chevys Cubans have magically kept trundling along since Castro was a young man. Are they resourceful? Yes. Are we envious? No. As employees of the government, soldiers must ‘make do’ with the equipment they have and, traditionally, Canadians have done a pretty miserable job of ensuring they get what they need.

A SHORT LEASH

The CV-90: A former contender for Canada's CCV Competition.

There hasn’t been a lot of positive press on the government’s decision to sole-source the purchase of the F-35 fighter jet, but one good thing it has done is highlight the government’s poor record on military procurement programs. Taxpayers are shaking their heads when they read the headlines about how long it has taken to deliver fixed-wing search and rescue (FWSAR) craft to the air force, how expensive it has been to build an ‘Arctic’ offshore patrol ship (AOPS) that doesn’t live up to its namesake, and how much money was wasted on running a Close Combat Vehicle (CCV) competition that the Army eventually concluded it didn’t need.

All this boils down to accountability, and it raises an important question: Could the Harper government survive another disastrous, scandal-plagued, billion-dollar procurement bungle?

Maybe not. This is why, from the outset, the government has billed the CSC program as a ‘fair and transparent’ competition. But things are not as they seem. Enter Mersereau’s bread crumb — the first indication that the integrity of the CSC program had already been compromised.

Mersereau writes: “There is discussion in industry circles that Canada has indirectly retained a third party to help make it a more informed decision on the CSC procurement strategy of MQT (Most Qualified Team) versus MCD (Most Capable Design). One would hope that if in fact the rumour is true, then industry would be given some insight into how the supplier was selected and the terms of reference established.”

Initially, it looked as though the CSC program was going to progress along the same lines as the Canadian Patrol Frigate project: two partially funded project definition contracts, with two separate industrial teams, would go head to head in order to offer Canada the most capable ship at the lowest cost. This fairly simple approach, known as “Most Capable Design” (MCD), is effective … as long as the government is realistic about what it can buy for the money it has.

TIPPING THE SCALES

But then a new method came to the fore, and with it questions about the integrity of the CSC program. The “Most Qualified Team” (MQT) approach is similar to the one used by the government when it selected Irving Shipbuilding Inc. for the bulk of the work under the National Shipbuilding Procurement Strategy (NSPS).

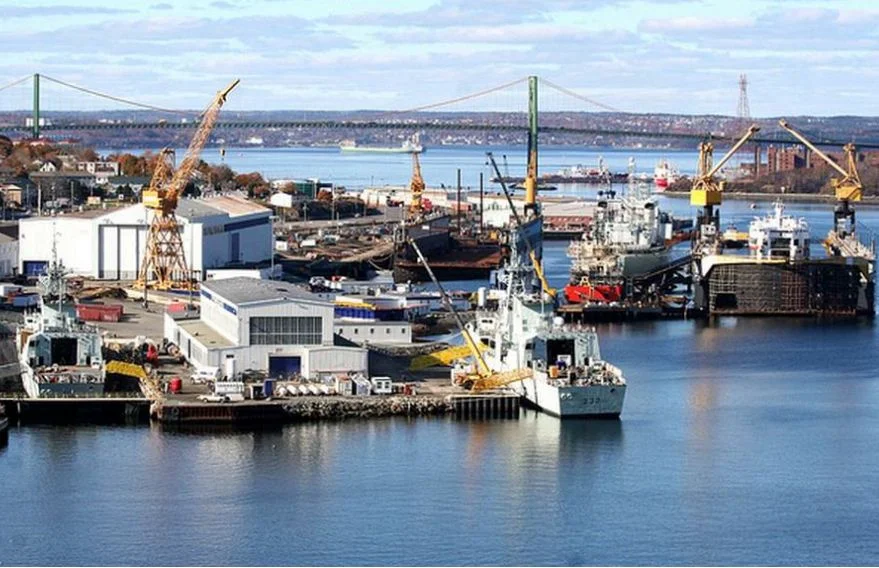

Irving Shipbuilding in Halifax, Nova Scotia

The problem with this is the use of arbitrary benchmarks. The government writes its own criteria, and then selects a ‘winner’ based on which contractor — or, in this case, team of contractors — meets them. It’s like opening a job up to all birds, and then stating that the successful applicant must look like a duck, act like a duck, and quack like a duck.

In regards to the CSC, the MQT approach heavily favours Lockheed Martin, and their competitors are acutely aware of this. But why, one must ask, in a ‘fair and transparent’ competition, would the government want to tip the scales in favour of one company over another?

COMMONSENSE SOLUTION?

One of the key problems with the CSC procurement program is Lockheed Martin Canada: The corporation is too well positioned to win the lion’s share of the work (and money). In fact, if this were a horse race, Lockheed started out of the gate when the Halifax-class modernization program began (some would argue even before that), positioning themselves at the finish line before the starting bell rang.

One of the Halifax-Class frigates with a 'bone in her teeth.'

To be clear, that’s not a problem for Lockheed Martin, but it is a problem for their competitors — and for the Harper government. Lockheed is wrapping up a very successful modernization of the RCN’s Halifax-class fleet, leading a team of Raytheon, Thales, BAE, and General Dynamics (among others) to install everything from new missiles and weapons to the ultra-complex system that will ultimately control them.

Besides being an ‘on-time and on-budget’ good news story, choosing Lockheed on the Halifax-class modernization also ensured seamless interoperability with the U.S. fleet — a priority in the Harper government’s now-defunct Canada First Defence Strategy.

Installing the same, or similar, systems on the CSCs means that naval personnel won’t need to go through a potentially costly and time-consuming training and adjustment period on the new vessels. Retraining sailors on brand new systems and having different systems between RCN ships doesn’t really make a lot of sense … especially considering that Lockheed Martin Canada invested millions in the establishment of a 100,000-square-foot Maritime Advanced Training and Test Site (MATTS) in Dartmouth, N.S., for the Royal Canadian Navy in 2009.

Furthermore, Lockheed’s relationship with Irving Shipbuilding has been particularly fruitful. During a time when military programs are blowing their budgets and experiencing delays, the Halifax-class modernization has earned high (and rare) praise from Canada’s Minister of Defence. “We couldn’t have done this without our tremendous partnership with the Canadian shipbuilding industry. Lockheed Martin Canada has taken care of all the integration software and combat management systems — a truly critical aspect of the modernization process,” said Rob Nicholson at a November 2014 press conference.

As the winner of the NSPS combat package, Irving wields a considerable amount of influence over the CSC program. After their proven partnership with Lockheed, what motivation would they have to work with another combat systems integrator? Relationships have been formed, they’ve been tested, and the combination is working … for Irving, for the Harper government, and for the RCN.

THE MAKING OF A WINNER

As many in the defence industry see it, MQT is the government’s way of manipulating the parameters of the competition to ensure a Lockheed win. The government makes the rules to favour one company, and when they play the game, that company wins. But Canadians aren’t looking at how and why the rules were made the way they were, they’re looking at what the referee does as the game is played. It’s like creating a new form of hockey where the rules say that the visiting team can’t use sticks. The ref will call a fair game, everyone in the stands will see that, and naturally the team without the sticks will lose. Were the rules fair? Not really, but whoever created them didn’t force the visiting team to play. Did the ref call a fair game?

Absolutely. Which begs the question, why did the visiting team step on the ice at all if they knew they’d have little chance of winning? The answer is simple: They were playing for the chance to win $26 billion, hoping for another ‘Miracle on Ice.’

The concern here isn’t about cost, public scrutiny, or even whether or not the existence of the report Mersereau alleged was necessary; it’s about the government’s commitment to fairness and transparency. One hand of the Harper government is over its heart promising to be honest, and the other hand is penning multi-million dollar contracts to companies that could have extreme bias over the outcome of the CSC program, directing them to come up with information that could influence who wins the $26 billion competition.

That company is Irving, which was allegedly paid upwards of $2 million in order to contract global consulting firm A.T. Kearney to weigh the merits of MQT vs. MCD. When asked about the existence of a report, Irving Shipbuilding and A.T. Kearney both declined to comment. A representative from Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC), however, provided the following response:

“The work focused on assessing the degree to which the current draft requirements for the systems and sub-systems, which will be potentially incorporated into the Canadian Surface Combatant ships, support competition for the selection of these systems. These draft requirements were presented to Industry during the five industry engagement sessions held over the past year, and will also be the subject of further industry engagements.”

PWGSC continued: “A decision with regard to the procurement strategy will be based on a number of factors, of which an independent review of the draft technical requirements is just one.”

The definition of “independent” is open to interpretation, but if the government really wanted to be convincing, why didn’t they commission the report themselves? Why contract Irving and risk compromising the integrity of the CSC program when PWGSC could have gone to A.T. Kearney directly?

There are a few simple reasons: it more than likely would have taken forever; perhaps another is that the public would have balked at the cost. And if that were the case, why not share the terms of reference with industry? In a supposedly ‘fair and transparent’ program, what’s with the secrets? Silence breeds speculation … and if we’re all buckled tightly onto the honesty bandwagon, why not set the record straight?

LAUNCHING A MISSILE

This leads us to a unique predicament. Industry reps won’t go on record, leaving mainstream journalists with little to run with until they are able to lay eyes on the report directly. And that, given the sensitivity of the document, would be next to impossible to retrieve through Access to Information.

A RIM-162 ESSM Missile

What little there is to be found on the CSC program, besides what’s already been written by Mersereau, has been penned by Michael Den Tandt, who is circling menacingly over the government’s head with headlines (“Breaking Lockheed Martin’s inside track at DND” and “Does Canada need an independent military?”) that make a Lockheed win seem anti-Canadian.

Den Tandt has also raised another important issue within the scope of the CSC program, namely Canada’s $800-million dollar investment in the Evolved Sea Sparrow Missile (ESSM) program.

At a time when the government has made deep cuts to the Department of National Defence budget and, coincidentally also to the procurement of munitions, the decision was made to invest $200 million in the development of the ESSM, adding another $600 million for future procurement and integration of the missiles.

That’s relevant not only because Raytheon is a close partner with Lockheed on the Halifax-class modernization project (and would be on the CSC project), but also because those ships currently use Sea Sparrow missiles. In fact, Canada has been using Sea Sparrow variants since the 1970s.

To think that the government would put up $800 million dollars in support of the ESSM program when 15 of their future warships wouldn’t carry them carries this reaction from a defence industry source: “At the end of the day, the thing is a complete charade. If they actually went and did this and invested the better part of a billion dollars, are you going to move to another missile system at that point?”

Den Tandt has been plucking away at the fabric of the CSC program, but hasn’t yet stabbed a knife through the middle of it. Again, that has to do with the availability of sources, and their willingness to talk. But that doesn’t mean that both he and Mersereau haven’t had an impact.

INDUSTRY (DIS)ENGAGEMENT

At a recent meeting between industry and PWGSC, a government official admonished defence execs about what has already appeared in the media. The relationship between both parties has become increasingly strained, largely because defence execs are losing/have lost faith in the process, yet can’t speak out for fear of future retribution. The government doesn’t hand out multi-billion-dollar rewards for blowing the whistle on questionable practices in military procurement programs. Speaking out could be disastrous; it could mean potentially losing other contracts, losing potential subcontracts from the CSC program’s big winners, or becoming pariahs within a very close-knit defence industry.

This has contributed to turning the government’s highly touted ‘industry engagement sessions’ into a farce. Their December meeting, set-up in a large hall with more than 50 representatives in attendance, lasted a mere nine minutes. If most of the players at the table of a poker game believed that the dealer was showing bias towards a particular player, why would they want to show the dealer their cards? Wouldn’t that just make it easier for the dealer to rig the game?

Understandably, the government realizes that they have a major problem on their hands. Even though a Lockheed solution seems to make sense, and the path to it is most easily reached through an MQT approach, they’re beginning to realize that going down that road will invariably result in a media circus. After the $26-billion pie has been gobbled up, tongues may be more inclined to wag, and Canadians will be left thinking our government has sold out to the Americans (again), overspent on procurement (again), shipped jobs overseas (again), and reduced the independence of the Canadian military.

And in an election year, that could be a crippling blow.

BACKDOOR APPROACH

You could be forgiven for thinking that the government’s agenda has ultimately been stymied by public scrutiny, but that wouldn’t make you any less wrong.

Before the end of the workday on January 20, reporter James Cudmore filed a story on CBC stating that government officials had met with “industry insiders” to inform them that Irving Shipbuilding had been chosen as the prime contractor on the $26-billion Canadian Surface Combatant program. On Tom Ring’s last day as Assistant Deputy Minister at PWGSC, he gave away the largest and most complex naval procurement contract in Canada’s history with nary a whimper. Apparently, that component of the CSC program wasn’t up for competition.

Passing responsibility for the CSC program onto Irving Shipbuilding may not have been entirely fair, but they are Canadian, if that’s any consolation. But just as their name implies, Irving is a shipbuilder. Considering that the government had been starving them of military shipbuilding contracts for decades, when (and how) did they become experts in the management of large-scale military procurement projects? Lockheed Martin, BAE, and DCNS have proved themselves in their respective home countries many times over in this department … but competence doesn’t really seem to factor into the equation here.

Choosing Irving Shipbuilding as the prime contractor solves a few problems for both parties. Because the project is taking place in their shipyard for the next 20 or 30 years, it stands to reason that they’d want to take the lead in the project. As for the government, assigning Irving Shipbuilding the responsibility to award subcontracts takes them out of the line of fire if and when Lockheed scores another big win in a Canadian military procurement program.

A leaked PowerPoint document from the January 20 meeting reveals that Irving will be responsible for awarding a contract for combat systems integration, and another for warship design. This seemingly hybrid approach may allow other defence contractors to theoretically obtain a larger percentage of the work, while still leaving most of the meat on the bone for Lockheed. The downside to that approach is huge: Warships aren’t Lego. Think of the man-hours (and the hundreds of millions of dollars) it took for BAE, DCNS, and Lockheed Martin to provide complete, cutting-edge, off-the-shelf warships for their customers. It would be like asking a Cadillac dealer for the shell of a car — with no engine, transmission, suspension, or parts — then asking a Mercedes dealer for all the working parts, and then heading down to the local mechanic and asking them to put it all together. Except, unfortunately, it’s a lot more complicated than that.

If you’re wondering why the government would ever try to turn our future fleet of CSCs into a bunch of overpriced Frankenships — something that runs completely counterintuitive to common sense — think of what’s at stake for industry. Think about how hard these companies will fight for a chunk of that business. Think about what transpired in order for this writer to produce this article. Think about Den Tandt’s articles, and why Mersereau put that bread crumb in that Defence Watch article. And then mix in all the other factors, such as the government’s international obligations, politics, public opinion, etc., etc., etc. You’ll find your answer somewhere in that dark forest, where there are 26-billion reasons for the CSC program to go wildly off course.

NAVIGATING A CHESSBOARD

No one is a victim here; no one besides the sailors that man the decks of Her Majesty’s ships, painting over the rust and machining parts that haven’t been manufactured for decades. RCN Commander Vice-Admiral Mark Norman will (has to) sell you our Navy, but he knows that the quality of our sailors aren’t matched by the condition of our warships. And yet, as the CSC program languishes in the ‘take-no-prisoners’ chess match of military procurement, he is forced to lean on allies and ‘make do’ with what he’s got.

There is nothing fair about the CSC procurement: not for the government, not for industry, and especially not for our sailors.