THE MEMORY PROJECT

(Volume 24-03)

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was fought during the First World War, over four days from April 9 to April 12, 1917. The battle has become known as a defining event in Canadian history. It was the first time that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps united, capturing Vimy Ridge from the Germans. This year marks 100 years since the battle that became known as the “birth of a nation.”

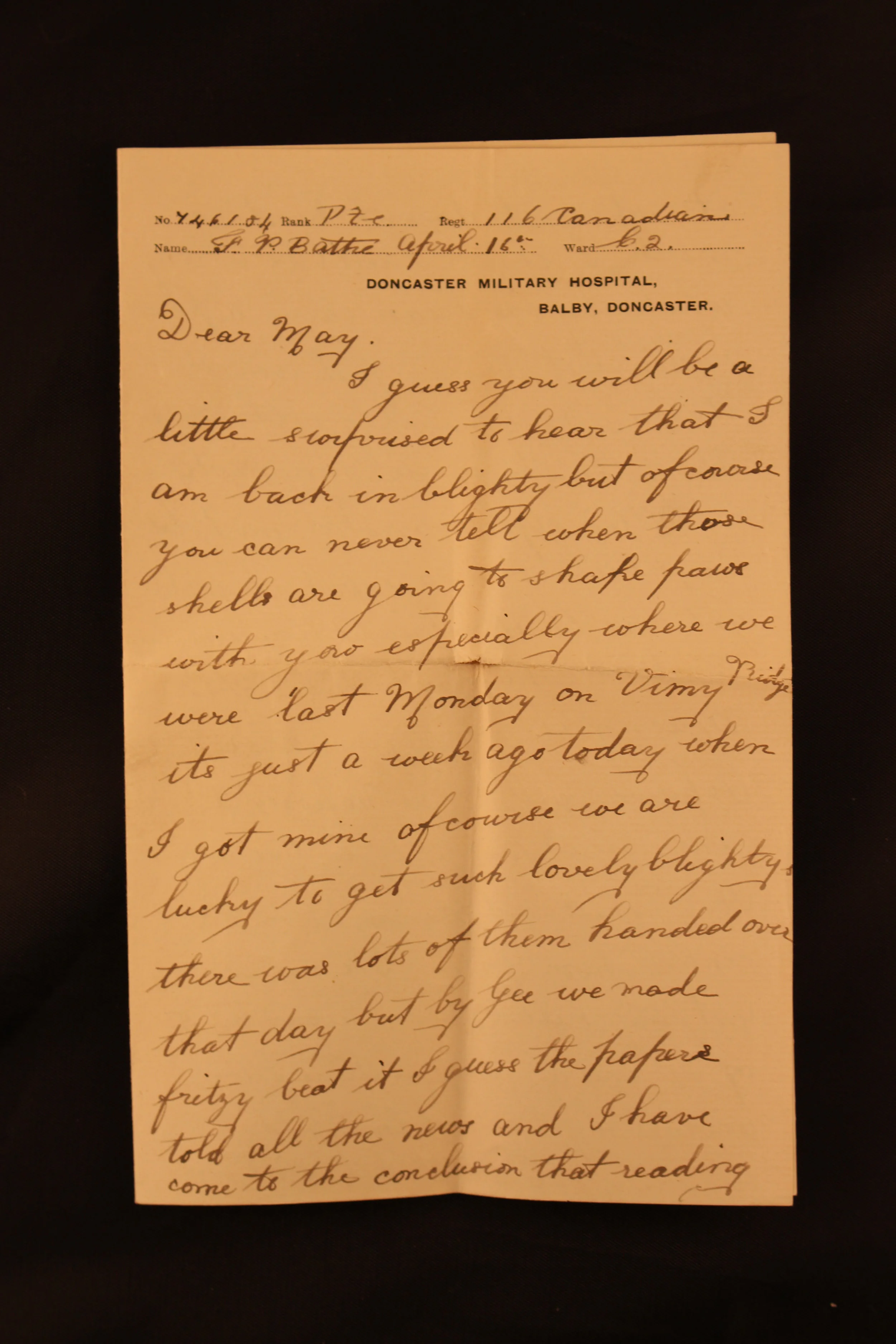

Francis Bathe was one of nearly 100,000 Canadians who participated in the Battle of Vimy Ridge, and was one of more than 7,500 soldiers wounded in the battle. Bathe was just 21 years old when he wrote this letter home to his older sister, while he was recovering from a shrapnel wound to his neck in a hospital in the north of England. He details, sometimes quite graphically, the tragedies of war. Yet this letter also brings to life an air of optimism about what the Battle of Vimy Ridge meant for the war effort.

Francis Bathe has reached hundreds of Canadians through his story of military service through The Memory Project’s online archive. To read or listen to more veterans’ stories, please visit The Memory Project website (thememoryproject.com).

Dear May,

I guess you will be a little surprised to hear that I am back in Blighty, but of course you can never tell when those shells are going to shake paws with you, especially where we were last Monday on Vimy Ridge. It’s just a week ago today when I got mine, of course we are lucky to get such lovely blightys. There was lots of them handed over that day but by gee we made fritzy beat it. I guess the papers told all the news and I have come to the conclusion that reading it out of a Toronto Empire is a little safer than doing the work, but there wasn’t a bad time that day.

Of course there was a few of our lads napooed but nothing like so many as they expected. I don’t think. The greater part of them were walking cases like myself with just small wounds, mine was a piece of shrapnel; it went in about the shoulder blade and came out in my neck and made a small hole of course about 1 ½ inches long, 1 inch wide, but I can’t imagine why it is so painless. Of course I’m not kicking but I was a little surprised at the size of it when it doesn’t hurt so much. I think I will be a long while before I can carry a pack again, but being a flesh wound it may heal quickly, and the only thing is it made my neck a little stiff and makes me hold my bean sideways, but it will get over that alright.

You remember Britton who married one of the Mac girls when you were in Oshawa? Well he is napooed and was blew completely in two. An H.E. [high explosive] shell got him right in the centre, poor fellow. The one which got me killed two and wounded 5 of us. One of the poor lads fell across my legs and I thought it was my chum but I rolled him over. He wasn’t dead but I yelled for

stretcher bearers and by that time he was gone. His two legs severed at the hip and poor lad was better dead. We captured about 3,500 that morning, and I should judge about as many were killed or wounded besides that. I think the 1st and 2nd Divisions did equally as well, by what I heard they were chiefly the Bavarians at that. They are notable fighters but our lads were better. Of course our lads had one thing — a good artillery fire ahead of them but they said about one half of the casualties were done by our own shells. Of course you can’t expect much else when they keep up within 25 yds of our barrage and some of the shells fall a little short but it was wonderful.

According to plans there were 5 shrapnel and 5 high explosive shells beside dozens of smaller ones which dropped anywhere to every 18 ft. We were lucky not to have to go over the top but were in supports and reserves. We left our little rabbit holes in St. Eloi wood at eight and went up to consolidate the trenches and dig a communication between ours and fritzys front line, that was where I got mine. By gee some of the lads were glad to get hit and come back, but you would be surprised to find out what wonderful spirits our lads had that night. They had a hard task but then it is a known fact the Canadians generally do the hard jobs better than most and are always just in the tough spots.

The French lost 80,000 in capturing Vimy; before then they handed it over to the Imperials and they turned round and lost it, so you can imagine what a place it was. You see it’s a ridge and those who hold the top of the ridge can look down over a stretch of 12 miles of fritzys territory and now they will rattle Sam Hill out of him. You see if they couldn’t move him from the ridge. Why if you look at a map, they were almost at a standstills but they took it and now fritzy will have to hike out. The papers give a very good account of it. There was only one correspondent that I saw around where we were and he came out of a dugout about 25 or 30 ft down.

By gee the Germans had tunnels and dugouts and caves about 60 to 75 ft down, and in most of them were electric light so they thought they wouldn’t have to move for a little while, but their lease expired Easter Monday and he certainly left the rent on the mantelshelf and beat it. You could see Battalions of them going through a village and they opened the liquid fire on them, and poor mortals didn’t like to take their own medicine; they handed over to the lads a year or two ago when they had us beat, but now we give it to them with their full interest. If they weren’t driven to it they wouldn’t do a great deal of scraping, but of course some will fight and it will take a few months to finish it yet. But this summer will do it alright.

Well I will write to you again. We are away up in Yorkshire as you will see by my address. So Goodbye.

Your Bro, Frank.