By Ashley Milburn

Over the past 10 years, the “silent services” of Asian navies have gone up-market. Fleets in the region now contain a range of imported and indigenous nuclear-powered, diesel-electric, and air independent propulsion submarines. Even the small city-state of Singapore, which is roughly equivalent in size to the city of Toronto, boasts an impressive subsurface capability. Last year, the Royal Thai Navy, which currently has no submarines in its order of battle, adopted a forward-looking “build it and they will come” strategy with the commissioning of a submarine squadron and a training centre.

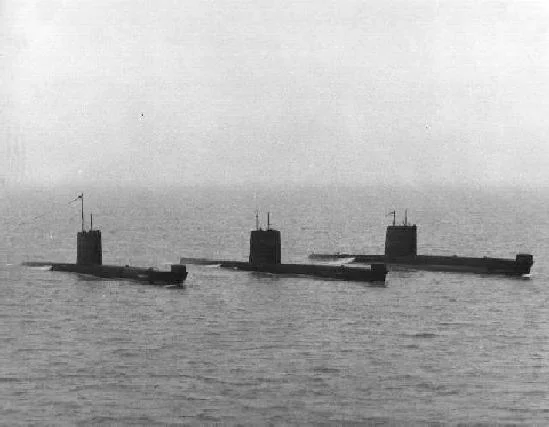

Indeed, trends in Asia, where some 200 submarines are said to be operational, deflate any notion that submarines are a bygone feature of the Cold War era.

Yet, in some corners of the region, the debate over the strategic rational for such a capability still continues. While Canada is no stranger to that debate, the public discourse over submarines is perhaps most instructive in Australia, where the government is trying to advance its Future Submarine Program while preparing to release its 2015 Defence White Paper.

Canberra has been struggling to determine the best course of action to replace its six Collins-class boats, and with good reason; the country’s projected 12-boat program will be the most expensive and technologically complex defence capability project in the history of the nation.

The fact that the Collins-class has been beset with problems since the lead boat was commissioned in 1996 has only fuelled the debate further. Issues throughout the entire life of the vessels, including accusations of mismanagement during the design phase, ongoing technical problems and capability deficiencies, as well as substantial manning challenges have all contributed to the boats’ low operational readiness rate. As a result, public enthusiasm for embarking on a replacement program — that would see the current submarine fleet double to 12 boats of an advanced design — has been difficult to muster.

Further complicating the Australian discourse is the issue of indigenous versus foreign design for the country’s future submarine fleet. The latest news out of Canberra indicates that, despite domestic pressure to build the boats at home, the government is leaning towards buying off-the-shelf stealth submarines from abroad, most likely from Japan.

Australia is not alone in trying to reconcile the desire for self-sufficiency in submarine capability, as a national security priority, with the limitations imposed by cost and technology. Indeed, there are parallels between the submarine debate in Australia and Canada. The Royal Canadian Navy and Royal Australian Navy are both medium-sized navies competing for scarce defence dollars within their national budgets.

HMAS SHEEAN in Freemantle, Australia.

Both countries are also maritime nations with a continental culture. As such, many citizens question the need for submarines at all and argue that the rationale for having the capability has never been properly explained.

The very nature of submarines precludes a certain level of discussion about their strategic, operational, and tactical applications. Nevertheless, the general utility of submarines is widely recognized. Deployed submarines can grant allied forces the ability to track enemy vessel movements, while at the same time limiting these movements through threat of engagement. Moreover, a submarine capability allows a navy to improve its strategic defences when operating in submarine-rich environments, like the Indo-Pacific, as it is widely acknowledged that submarines themselves are amongst the most versatile anti-submarine warfare platforms available.

The fact remains, however, that submarines are complex, highly specialized assets that function with minimal margins for error. Subs must undergo rigorous technical and certification processes that, as a rough measure, require three boats rotating through the maintenance cycle in order to maintain one operational boat at sea. As such, the submarine game is not one that countries enter into lightly.

Given the level of investment required, there are some who argue that the submarine debate needs to be located within the context of an assessment of what the operational maritime environment will look like beyond 2020. It is true that naval procurement decisions cannot be made without thorough scans of the environment, and a thorough understanding of security threats. However, this is easier said than done. The future is impossible to predict with precision, geo-political perceptions cloud national realities, and procurement processes for multi-billion-dollar defence projects are necessarily attenuated.

Australia hopes to tackle some of these issues with the release this quarter of its 2015 Defence White Paper. Like any defence policy, the White Paper will aim to define the connection between strategic outlook and force structure, and establish concrete links between equipment acquisitions and the budget. From a naval perspective, two issues will undoubtedly be at the forefront: the problematic Indo-Pacific maritime security environment and the potential role of submarines.

It would be wise for Canada to take note of Australia’s submarine discourse as these are certainly critical issues that are likely to figure in future Canadian naval calculations as well. In the meantime, the debate continues.