Swift execution of guilt during the Great War

By Matt Moir

A British soldier convicted of desertion is tied to a post behind the front lines during the Great War. He will be executed at dawn by a firing squad. Often, these men suffered from what was then called shell shock, and is now referred to as post-traumatic stress disorder.

In the early heady days of the most vicious human conflict the world had ever seen, the young men of Europe flooded into recruiting stations to volunteer to their bodies and valour.

Across the Atlantic, the opening rounds of the Great War had a similar intoxicating effect on Canadians. Able-bodied men, eager to demonstrate their allegiance to King and Country, dove headfirst into bloody combat.

The romance with combat ended swiftly, of course, but not before this country sent more than 420,000 Canadians overseas to fight during the First World War. Nearly 61,000 were killed, though not all by enemy fire.

For a small handful of Canadians — barely more than two dozen — death came via the firing squad, their breath forever extinguished by their comrades’ expert shots.

The crime of desertion

There were 306 military executions carried out by the British military leadership against members of the armies of Great Britain and the Commonwealth. Of those executed, 25 were members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

The men executed by their brethren came from big cities like Toronto, Winnipeg and Montreal, and small towns like Bouctouche, New Brunswick, and St. Catharines, Ontario. They were young, for the most part; the average age was 25. The youngest soldier had just celebrated his 20th birthday.

The overwhelming majority were put to death for the crime of desertion. In the Manual of Military Law, a guidebook distributed to Canadian Expeditionary Force units, the language describing desertion is bland: soldiers are warned against “leaving one’s post” or “encouraging others to desert.”

For the Allies entrenched in the meat grinder that was the Western Front, however, the act of abandoning one’s post was more than just a serious offense. It was personal a betrayal: a betrayal of one’s brothers-in-arms, a betrayal of one’s country, a betrayal of one’s mettle. At the time, the punishment of death was, for many, an appropriate one.

An exhibition of a soldier in a trench suffering from shell shock. For thousands of soldiers in the Great War, the fear, paranoia hysterical crying, terrible nightmares, mutism, fatigue, facial tics, and tremors were symptomatic of shell shock.

Over the last century, however, the justness of those executions has been challenged.

Advocates maintain that most of the more than 300 soldiers shot and killed by British firing squads were not put to death for fleeing their posts or abandoning their comrades, but for having the misfortune of having suffered from a debilitating disease — shell shock — and having served under a harsh, uncaring British military leadership.

But contemporary research points to a more nuanced picture. As we approach the 100-year anniversary of the most gruesome and cruel fighting of the First World War, it’s important to explore the tragedy of the Canadian executions unencumbered by the fog of war, and memories that have grown sentimental over the passage of time.

A ‘very disturbing sight’

At the Second Battle of Ypres in the spring of 1915, on the muddy, windswept plains of Belgium, Germany for the first time used poison gas against its enemy.

Major Victor Odium of the 7th Canadian Battalion said this of the Germans’ use of poison gas: "We couldn't visualize an attack with gas, we could not guess where the gas would come from or how we could recognize it when it did come, and we did not know what were the necessary precautions."

The effects were, according to personal accounts of soldiers on the Western Front, hellish.

Of those on the battlefield suffering the effects of the chlorine gas, Canadian soldier Major Andrew McNaughton remembered, "their eyeballs showing white, and coughing their lungs out — they literally were coughing their lungs out; glue was coming out of their mouths. It was a very disturbing, very disturbing sight."

The weapon outraged Britain, but the Allies soon developed their own poisonous gas reserves to use against the Germans.

From a 21st century perspective, it’s difficult to imagine how a soldier from the First World War confronted what, at the time, was a level of barbarism unique to human history.

Technological advancement made widespread slaughter in the First World War far more efficient than any previous conflict in human history. For the first time, men could be killed by weapons fired from many miles away, or by simply breathing.

For thousands of soldiers, the fear and paranoia brought on by mass, mechanized killing led to shell shock: paranoia, hysterical crying, terrible nightmares, mutism, fatigue, facial tics, and tremors.

In a letter sent from the front lines, British soldier Corporal Henry Gregory wrote: “It is heartbreaking to watch a shell-shock case. The terror is indescribable. The flesh on their faces shakes in fear, and their teeth continually chatter. Shell-shock was brought about in many ways; loss of sleep, continually being under heavy shell fire, the torment of the lice, irregular meals, nerves always on end, and the thought always in the man's mind that the next minute was going to be his last.”

One hundred years after it emerged from the trenches of Europe, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) remains a devastating affliction for men and women in uniform. At least today, however, PTSD is commonly accepted as a genuine and serious wartime injury.

During the First World War, there was no such consensus; it was even described as “a manifestation of childishness and femininity” by Sir Andrew MacPhail, in his book The Medical Services, which was published as part of the Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War, 1914–19.

Shell shock takes its toll

Frederick Arnold was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1890. He enlisted in the Canadian military in Quebec three weeks after the outbreak of the Great War.

In early June 1916, Arnold left his battalion in France. He was arrested on June 27 and, a few weeks later, executed by a firing squad. Arnold was 26 years old.

Historian Andrew Godefroy has said that “Arnold did not deserve a death sentence by any means, especially if he was only absent for a few days.''

Not only was Arnold only away from his battalion for a very short period of time, his medical records indicate he was suffering from shell shock. He was, of course, executed anyways.

Both 25-year-old Leopold Delisle and 21-year-old Stephen Fowles received treatment for shell shock; both were killed by firing squad.

Thousands of Canadian soldiers were diagnosed with shell shock during World War One. Of the 23 Canadians executed for desertion or cowardice (two were put to death for murder) at least three suffered from shell shock, and historians cannot be sure that the number wasn’t, in fact, higher.

The sad fate met by Arnold, Delisle and Fowles contributes to a popular history that tells us that the young men executed during World War One suffered from a horrible illness, yet were still put to death by an unfeeling military leadership ignorant of the medical realities of what was incapacitating so many of its troops.

There is an undeniable truth to that narrative; medical experts were, indeed, confounded by the affliction.

Queens University’s Teresa Iacobelli is one of Canada’s leading experts on the execution of Canadian soldiers during World War One. In her book, Death or Deliverance: Canadian Courts Martial in the Great War, Iacobelli writes that in 1915, doctors believed that shell shock was caused by the literal explosion of shells; a soldier unfortunate enough to be too close to artillery fire would suffer debilitating injury to his nervous system.

According to Iacobelli, some doctors speculated that “tiny particles from exploding shells injured the brain, while others blamed the explosive gases within the shells.”

Some within the military and medical communities viewed it as nothing more than cowardice. A prominent Canadian doctor named Sir Andrew MacPhail opined that shell shock was a “manifestation of childishness and femininity” and feared that the effects of shell shock could, if untreated, spread throughout a battalion.

Thus, treatment was often harsh and included solitary confinement, electric shock therapy, and shaming. (There was, however, a class element. Unlike working-class soldiers, officers from the higher social classes largely didn’t suffer the pain and indignity of electric shock, but were given the opportunity to rest at placid country estates far behind the front lines.)

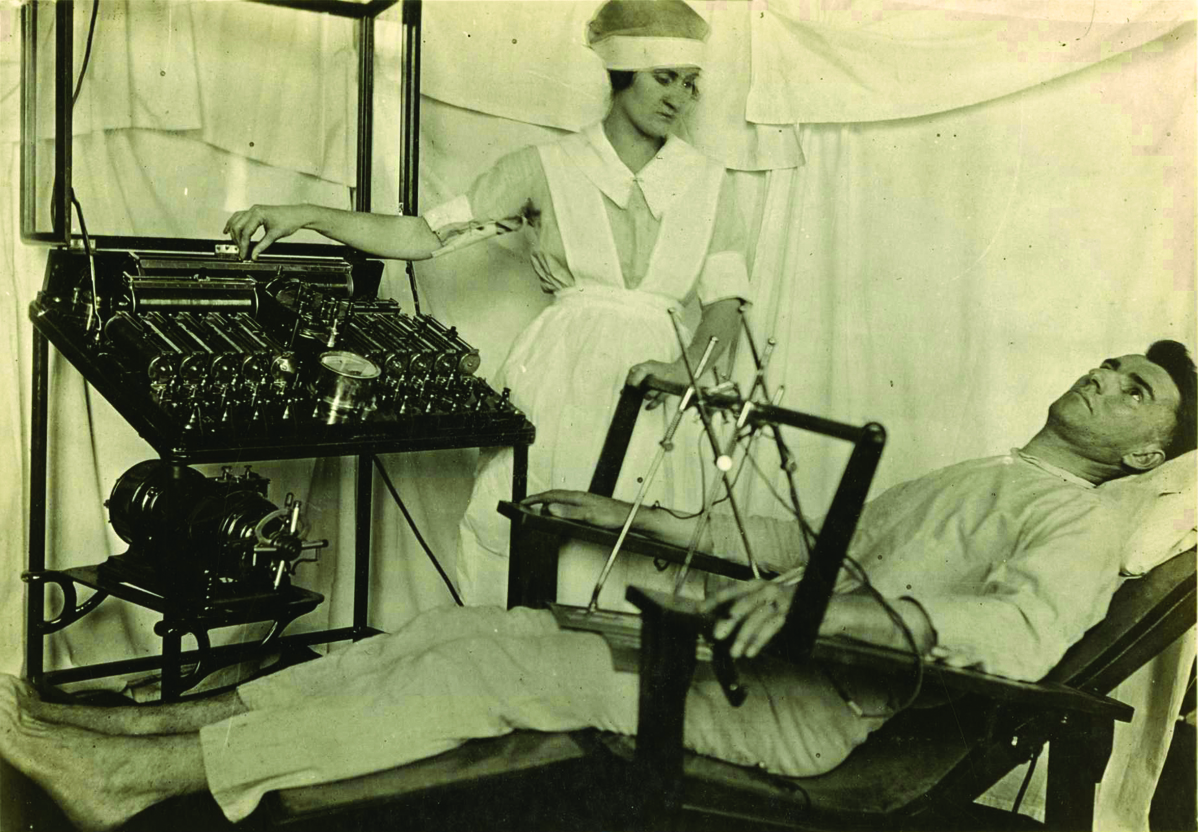

A shell-shocked soldier being treated with electrical shock treatment by a nurse. The Bergonic chair was an aparatus devised to administer general electric shock treatment for psychological effect, in psychoneurotic cases during the Great War.

The desertion myth

But the reality of the circumstances surrounding shell shock and the execution of soldiers is far more complex.

First, doctors did make — albeit slowly — progress in better understanding shell shock.

Dr. Charles S. Myers, for example, determined that the effects of the disease were not physical but psychological, and he convinced British officials to develop specialist hospitals in the United Kingdom for individuals who suffered the most severe cases of shell shock.

And on the military front, many commanders were not nearly as merciless as they have often been portrayed.

“Shell shock is one of the prevailing images we have from the First World War. I think this image that’s portrayed in film, in television shows and in post-war novels has been of an underage soldier and a shell-shocked soldier,” says Iacobelli. “We assume that anyone who was in that position [to be executed] was there because he fled because he had shell shock. And there is also that image that he fled in the middle of a battle and he didn’t go over the top and charge. He just stayed there or ran in the opposite direction.”

Iacobelli says that narrative is a myth and that, in most cases, desertion did not work that way.

Desertion “occurred when the soldier was already behind the front in a back position, or he was on leave and decided not to return. So that image we have of a soldier refusing to go over the top is false.”

Iacobelli’s research compared the cases of executed Canadian soldiers with cases in which soldiers had their death penalty sentences commuted. She looked at hundreds of court martial transcripts and letters from commanding officers and found that, while 22 Canadians were executed for desertion or cowardice, 197 soldiers convicted of similar crimes had their death penalties commuted.

These commutations, according to Iacobelli, refute the stereotype of the callous and cold military commander minimizing the plight of soldiers on the front lines.

“There were a lot of leaders that said don’t execute because they may have been sympathetic to the plight of the soldier’s mental state or physical state. Maybe they said the battalion itself didn’t need an example to be made. They had wiggle room there to exercise some mercy, and I don’t think that necessarily comes out in the popular media.”

The perceived strategic incompetence of World War One leadership has given us the idea that front-line soldiers were lions led by donkeys. It’s that antipathy toward commanders from which we have likely inherited an under-appreciation of their, in many examples, sympathy for the troubled front-line soldier.

Then and now

In 2006, the British government gave a formal posthumous pardon to all 306 British and Commonwealth soldiers executed by firing squad for desertion and cowardice between 1914 and 1918.

The move came after a lengthy campaign by descendants of executed soldiers. Families argued that their long-lost relatives were suffering from shell shock and that their executions were a grave miscarriage of justice. Some historians voiced discomfort over the decision.

McGill University’s professor emeritus Desmond Morton, a noted Canadian military historian, argued that some of those included in the Commonwealth-wide pardon were probably authentic deserters who let down their comrades and were not suffering from the effects of shell shock.

Morton is quoted as saying that commanders executed deserters for good reason, and that “if everybody who decided to flee fled, where would the army be?''

The debate surrounding whether or not executed First World War soldiers were, indeed, victims of significant mental health injuries and should have been posthumously pardoned was an important one inasmuch as it forced us to look critically at our shared history.

But what’s of crucial importance today is that our society looks critically at the mental health crisis that has practically engulfed the modern Canadian military.

We know that PTSD and psychiatric conditions are the second-most common cause of disability claims among those who served in Afghanistan, and we also know that depression, substance abuse, violence and depression are a reality for far too many veterans.

It is tragic that a young man like Frederick Arnold, suffering from shell shock, was killed by firing squad; it would be equally tragic to let the modern soldier who shares the affliction suffer by way of apathy.

Evolution: From shell shock to PTSD

Throughout human history, society’s awareness of the psychological impacts of surviving conflict or witnessing troubling or catastrophic events has proven remarkably robust.

Literature from as far back as ancient Mesopotamia and Ancient Greece gives us clear descriptions of individuals’ combat-induced post-traumatic symptoms and, by the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, modern psychiatry began documenting examples of man-made disasters resulting in what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Survivors of enormous railway disasters, for instance, were struck by symptoms recognizable to many veterans of modern combat.

In the 18th century, a debate emerged over the causes of “hysteria.” One school of thought believed that microscopic lesions of the spine or brain caused mental symptoms, while others embraced the idea that emotional shock was the fundamental cause. This controversy lasted until WWI.

Mental health injuries became apparent very early in the First World War in amounts that had not been anticipated. In 1917, a respected German psychiatrist named Robert Gaupp said that the “big artillery battles of December 1914 … filled our hospitals with a large number of unscathed soldiers and officers presenting with mental disturbances. The main causes are the fright and anxiety brought about by the explosion of enemy shells and mines, and seeing maimed or dead comrades … The resulting symptoms are states of sudden muteness, deafness, general tremor, inability to stand or walk, episodes of loss of consciousness, and convulsions.”

It was not uncommon for soldiers suffering from shell shock to be viewed as nothing more than cowards, and many suffered punitive ‘treatments’ for their ailments, including electroshock therapy and solitary confinement.

During the interwar years, the term shell shock was replaced with combat fatigue or battle exhaustion, but erroneous beliefs with regards to the nature of the affliction were still readily held.

It was, for example, commonly believed that combat-related trauma was a short-term illness, and some soldiers were, because of their inherent psychological weakness, more ‘predisposed’ to suffer trauma than others.

This, inevitably, added to the shame of those who suffered.

In a military context, the Vietnam War was the catalyst for the most significant turning point in the history of psychological war trauma. Psychiatrists could not ignore the numbers of men returning home with symptoms initially labelled as “post-Vietnam syndrome.”

Veterans of the conflict waged a long and ultimately successful campaign for greater recognition of their suffering; in 1980, PTSD was included in the American Psychiatry Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Today, the Canadian Mental Health Association defines PTSD as a mental illness involving “exposure to trauma involving death or threat of death, serious injury or sexual violence” and treatable through psychotherapy, counselling, medication and support groups.

PTSD and other war-related ailments are a significant problem in the Canadian military community.

Psychiatric conditions are the second-most common disability claim of the 40,000 Canadian soldiers who served in Afghanistan. Troops who served in the Afghan War made nearly 3,500 disability claims for psychiatric conditions such as PTSD, depression and substance abuse, according to Veterans Affairs.