The Importance of trench papers in the Great War, Part 1

With little access to news from home, soldiers in the trenches took matter into their own hands and created frontline newspapers

By Kyle Falcon

From the October 2015 (Volume 22 Issue 9)

As armies began to dig-in in 1914, a network of publications emerged in the trenches. First appearing in German and Austrian units as a response to the lack of availability of national newspapers on the front, these first trench papers were produced from the top down, edited by staff officers. However, as the war progressed they became predominantly the domain of soldiers, especially in the allied armies where the papers were from the very start, written by the soldiers themselves.

Finding value in their ability to entertain troops, sustain morale, and build camaraderie, some senior officials encouraged soldiers to produce their own papers. While some were more successful than others, newspapers and journals emerged across First World War battlefields and training camps right up until the end of the war.

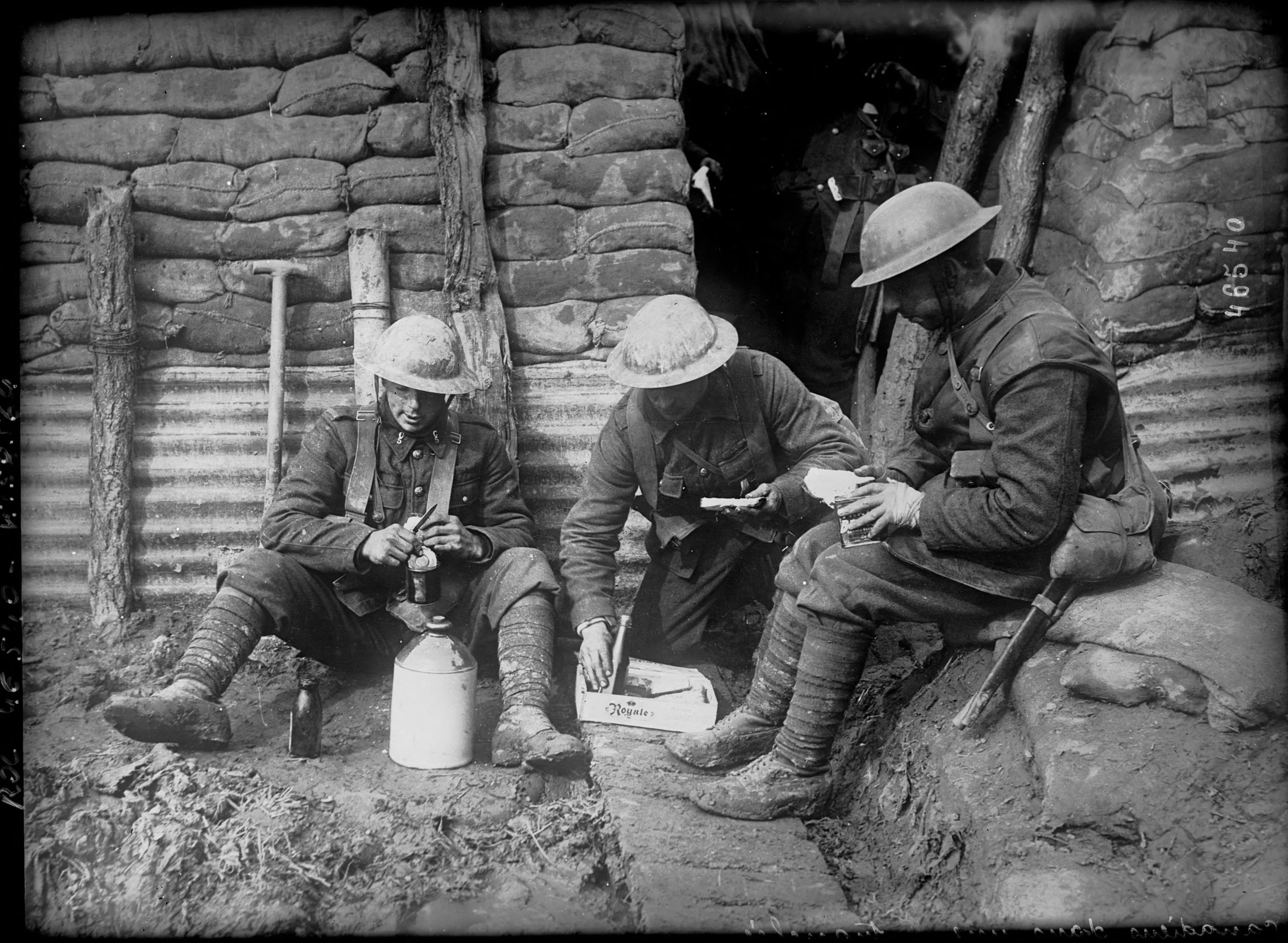

Soldiers gather round to hear the latest news. (imperial war museum)

The content of these newspapers was predominately satirical, but they also reported on news relevant to soldiers and provide an interesting perspective for contemporary observers. Historians have benefited from such a view of the war and it is the goal of this article to share these insights from a Canadian perspective. The contents of British, French, and German trench newspapers have provided the source base for several important cultural studies. For example, in Troop Morale and Popular Culture in the British and Dominion Armies, 1914-1918, author J.G. Fuller uses trench newspapers to argue that the successful transference of many facets of British civilian life to the front (i.e., sports leagues and music concerts) allowed the citizen soldiers of Kitchener’s Army to adjust to their new circumstances and therefore sustain a level of morale that could withstand the devastation of the conflict.

But who contributed to these publications? What did they write about and for what purpose?

First, not all papers came from the soldiers. There also existed official or semi-official papers such as The Canadian War Pictorial published by the Canadian War Records Office of the Canadian government. Nor were they strictly the work of units at the front. Chevron to the Stars was a trench paper that began at a Canadian training school, and the WUB (of the 196th Western University Battalion), was first published at Camp Hughes.

Unfortunately, with the exception of a handful of newspapers, most have left behind a scattered record, leaving historians to make educated guesses as to the number of papers actually circulated during the war. Less than 200 of an estimated 400 French newspapers have survived. Historians of the British and Dominion newspapers give a similar figure.

While these numbers are impressive, their geographic reach is perhaps even more significant, offering historians a window into almost every theatre of the war. The majority came from “somewhere in France,” but they were certainly not confined to the Western Front. The Silent 60th was first published aboard the HMT Scandinavian. The Peninsula Press (an Australian paper) was published on the island of Imbros in Turkey and the Beach Rumours (a British paper) at Cape Helles on the Dardanelles. Others were produced in the Middle East and Salonika.

It was not just the British and French troops who published newspapers; Russian soldiers also read trench papers when available during the first World War.

Their distribution was also not confined to the battlefields. The famous British paper The Wipers Times was so popular that its editions were re-published in London for general distribution before the end of the war.

Who wrote in these trench newspapers and what did they write about? While anyone could contribute, it appears that most editors came from some level of authority. French Historian Audoin-Rouzeau identifies that high-ranking officers and generals represented less than 2 per cent of the editorial staff, half of the staff tended to be composed of lower ranks such as corporals, while non-commissioned officers and subalterns each made up a quarter of the staff. As for British and British Dominion papers, Fuller was able to identify the ranks from 66 editorial staffs, 27 were composed of officers, 25 from other ranks and only 14 had both.

The ranks of the writers are far more difficult to assess, but some papers made it clear that anyone could contribute. Certain papers even attempted to overcome the disproportion of officers and made it a point to stress that it intended all ranks to contribute. As The McGilliken stated:

“It has been whispered that too much prominence has been given to the Officers in this paper … If that be so, it is certainly not through any wish of ours. It has always been our aim to make the paper of as wide an interest as possible … therefore again we take this opportunity of saying that the columns of the paper are always open to everyone in the Unit, and that any articles for publication, or items of interest will be gladly received.”

Vestiges of the lower ranks’ contributions can nevertheless be found in the texts. For example, some articles were signed off with the monikers “Pte.”

As for content, humour was preferred. As the The Listening Post exclaimed in its inaugural edition: “read me thoroughly — and laugh. — If I am not funny enough this time, then tickle your paper with pen or pencil and tell me the funny things that happen and I’ll do my bit.”

The papers were filled with poems, songs, short stories, the occasional serious matter or obituary, and provided readers with the results of various sporting clubs initiated by men on the front, such as football, baseball, and boxing.

Given these facts, the trench newspapers have been used to elaborate on a variety of themes relevant to soldiers’ experiences in the First World War. First, the importance of national cultures, their transference to the front and the creation of a new trench culture that emerged in relation to those pre-existing attitudes, concepts, and norms. Second, the role of agency — the need to be agents in a war otherwise beyond their control influenced the need for some Canadian soldiers to express themselves in the trench press.

The purpose of these three articles is to showcase the trench newspaper’s value as a historical source through the Canadian context. These articles will show a side of the First World War not often depicted but worth acknowledging. Furthermore, they provide insight on the humour and light-heartedness the troops used to combat not only the horrors of trench warfare, but also the boredom and monotony of trench life. Although Canadian trench papers have been examined in the historical literature, they have only been used in a wider context or for comparative purposes. The stories contained within them warrant their own space. The purpose here is to share them.