Q&A with Lieutenant Commander Christopher Rochon, Commander of HMCS Whitehorse

By Evelyn Brotherston

LCdr Christopher Rochon, speaking on his radio to the commanding officer of HMCS Nanaimo (seen through the fog in the background), during a seamanship evaluation (you can see Nanaimo’s ship’s company formed up on the forecastle) off the coast of northern California en route to the OP CARIBBE area of operations (AOO) on February 17, 2015. (Cpl. Blaine Sewell, DND)

This spring, HMCS Whitehorse, under the command of LCdr Christopher Rochon, participated in numerous high-profile drug busts on the high seas, as part of Operation CARIBBE, Canada’s contribution to a multinational campaign against illegal drug trafficking in the South Pacific. We spoke with LCdr Rochon to hear more about how the Royal Canadian Navy tracks and intercepts ships, and how they work with their partners in the American Navy and U.S. Coast Guard. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

LCdr Christopher Rochon (left) oversees the line handling during an alongside, with the ship’s XO, Lt Lucas Kenward, at Puerto Quetzal, Guatemala, on March 16, 2015. (MS. William Dennis, DND)

EdeC: Can you describe how you go about finding and tracking ships carrying illegal drugs?

LCdr Rochon: While we’re deployed, we are under the tactical control of an organization called the Joint Interagency Task Force South (JITFS); they’re responsible for coordinating, controlling, and building a picture of what's happening out on the water. We work to develop a picture, then look for inconsistencies — things that don't seem to fit — and combine it with any other information that may come in.

EdeC: Do you know whether or not a ship is carrying illegal cargo before you move to intercept it?

LCdr Rochon: Sometimes. There may be indications, but it’s never a sure thing, unfortunately. Part of the problem is you’re trying to find vessels in a vast ocean. But there are signs that give you an indication.

EdeC: Can you tell me what kind of signs?

LCdr Rochon: I can’t really go into specifics on that. Things tend to change; it’s very fluid, very dynamic. Of course, ourselves and those trying to smuggle drugs through the area are constantly adjusting to each other. We try to hold specifics close to our chest, so that the other side can’t adjust more quickly than we can — and hope that it gives us the upper hand for a bit longer.

EdeC: What kind of boats are these people operating in?

LCdr Rochon: There’s quite a wide range, actually. If you look at the first instance we were involved in, it was a coastal freighter. It was about 1,500 tons, in very, very poor shape — it was not an overly sea-worthy vessel. In the second incident it was a small local fishing-type vessel, a fast mover, with a couple of outboard engines. It changes all the time. Again, it’s a very dynamic environment out there.

EdeC: How does a boarding party work?

LCdr Rochon: I can tell you about the part we play, supporting the Americans. I work very closely with the officer in charge of the boarding team; in this case it’s the United States Coast Guard team that’s deployed with us. We work together to look for indicators, trying to identify ships that are suspicious. Then it’s a very quick process: they get their team ready, we do rules of engagement briefs, we define what the role of our staff is — there’s a separation between where our engagement stops and things become the sole responsibility of the U.S. Coast Guard. From that point on, what the U.S. Coast Guard boarding team does on board the ship is based on their policies and procedures and it’s out of my experience level, not actually having been on their team. They tend to keep their procedures to themselves, again for their own protection and security requirements.

EdeC: Are there any Canadians in these boarding parties?

LCdr Rochon: Not on this deployment. The boarding party itself is entirely U.S. Coast Guard.

EdeC: Is that because the rules of engagement for the Canadian Armed Forces don’t extend to include boarding?

LCdr Rochon: Yes and no. There are a lot of factors that go into this, including bilateral agreements, including what our actual mission is, and what our government has agreed to be a part of as part of this deployment. We have a role as a ship; we’re a coastal defence vessel (CDV), so we don’t have huge crews capable of supporting long-term, sustained operations. It works very well, though, keeping the separation as we have it.

LCdr. Rochon (left), speaks with LCdr. Jeffrey Hopkins, Commanding Officer of HMCS Nanaimo (right) prior to departing from Puerto Quetzal, Guatemala on March 18th, 2015. (Lt. (N) Paul Pendergast)

EdeC: Can you tell me more about what your role is?

LCdr Rochon: Our role is twofold. The biggest part of what we do is to build the picture in the area, using all of our assets, using our sensors, using our people and talking to local vessel traffic — trying to build a picture of what’s moving, what the normal traffic patterns are, and looking for those pieces that may indicate that someone might be suspected of smuggling drugs. The second piece of that is once we do have a target, we provide logistics, transportation, and security support for the U.S. Coast Guard boarding team, so that they are freed up to focus on the actual vessel intervention itself. So we’ll provide transportation, we’ll provide security, and we’ll stand watch for them on the outside to make sure they aren’t interrupted while they’re boarding. A lot of these incidents are long-term; the boarding of the coastal freighter took over three days. We’ll provide food support, we’ll bring them back and forth so guys can have showers, and we’ll give them a place to base themselves out of. We also provide coordination support between our U.S. allies down there — the U.S. Coast Guard and United States Navy. These operations require a lot of communication, so we provide that.

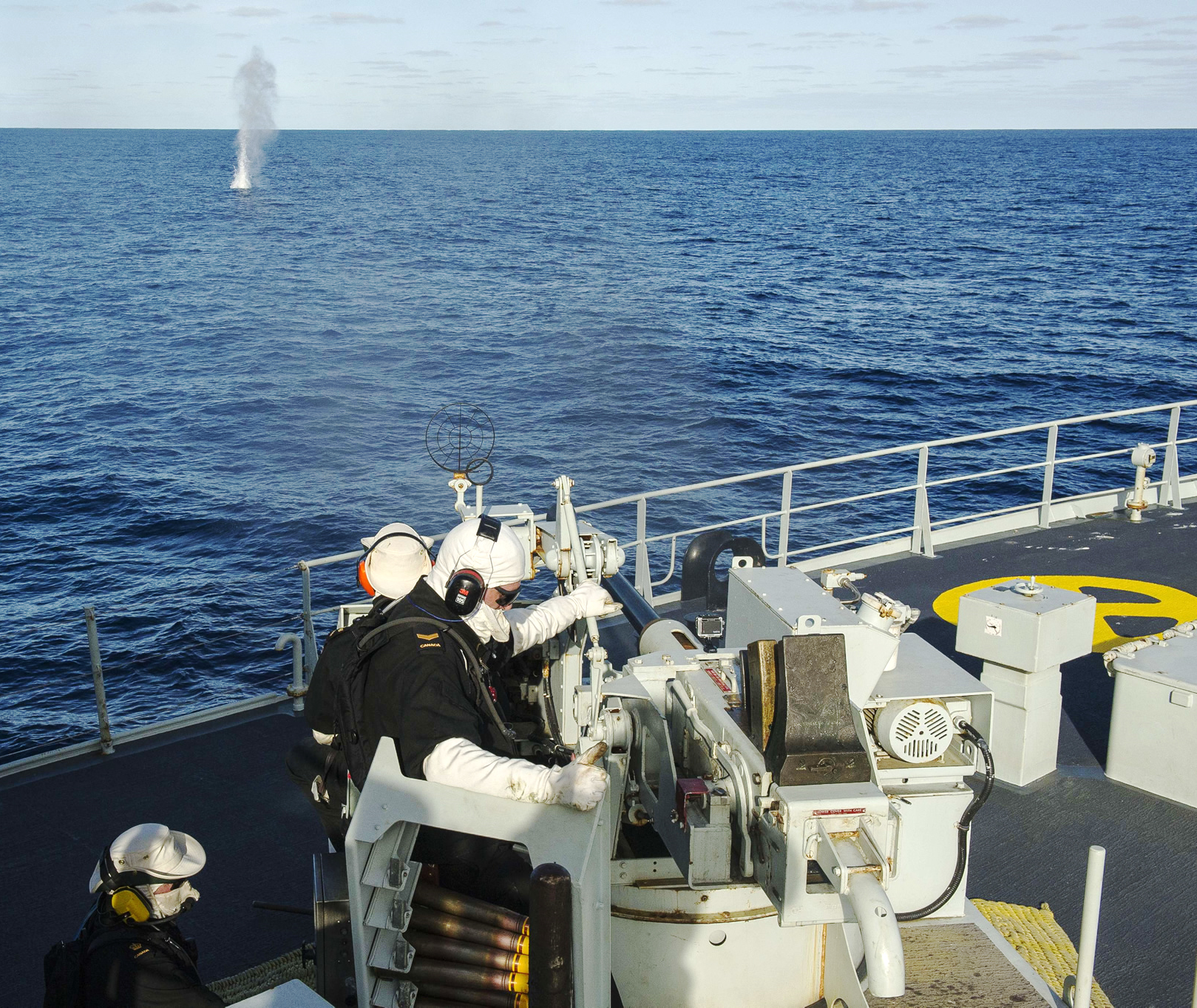

Crewmembers from HMCS Whitehorse conduct weapons maintenance on the 40mm gun while patrolling the Eastern Pacific on Operation CARIBBE. To date this year, the Royal Canadian Navy has assisted in the interception of more than 8,000 kilograms of cocaine while patrolling the Eastern Pacific and Caribbean Sea. (DND)

EdeC: Are the boarding parties based off of American ships, or are they disembarking off Canadian ships?

LCdr Rochon: We actually carry one of the U.S. Coast Guard boarding parties. It’s called a law-enforcement detachment, and they do disembark from our ship.

EdeC: When you’re gathering information, does it ever involve docking in port, or does it all happen at sea?

LCdr Rochon: It’s generally all at sea.

EdeC: Is it all done with instruments, or do you speak with local people?

LCdr Rochon: Mostly it’s instruments and talking to aircraft — we’ve got Canadian and U.S. aircraft that support this operation. They’ll provide a larger picture and we’ll be able to go out and actually get a closer look, and get a better idea of what's out there. Sometimes we’ll send people out to actually talk to local vessels, and find out whether or not there are people fishing in a given area, and whether that’s common, whether there are actually fish going through.

EdeC: What are the risks associated with what you’re doing?

LCdr Rochon: You’re dealing with drug trafficking organizations — there’s always going to be some degree of risk, because there’s so much money involved. That being said, the people that are actually doing the transportation through these areas are local vessel traffic — these aren’t hardcore drug lords or anything. The worst that they’ll do is try to run. Once they figure out that they can’t run, most of them are very compliant; they understand that they’ve been caught and there’s not much they can do about it.

EdeC: What’s the biggest challenge then, when it comes to intercepting ships?

LCdr Rochon: It really depends. Again, it’s really dynamic. It depends on the vessel you’re dealing with; it depends how far away you are when you get an indication; it depends on how fast they can go versus how fast we can go. How far away from land they are is another big one, especially if they are trying to aim for someone else’s territorial waters. If you’re dealing with a small boat, they may not have that much fuel, so they may be able to go faster, but you might be able to catch up later on. The weather is also a big deal; trying to both find and do interceptions in heavy weather always makes things more complicated.

EdeC: Does it ever happen that ships get away?

LCdr Rochon: Yes, sometimes they do. If you look at our second incident, unfortunately the vessel itself did get away, but they actually dropped their cargo in the water. That’s a common thing as well. And for us, that’s a win in itself. That was 600 kilograms of cocaine that they ended up just dropping, so that meets our objective.

EdeC: How long is a typical deployment for you?

LCdr Rochon: Generally from leaving Canada to our return back home, they are two to two and a half months.

EdeC: What’s the experience of being at sea for that length of time like? Do you enjoy it?

LCdr Rochon: Absolutely. You can do all the training and all of the local stuff, but to go off on a mission, a deployment, to have success, to work as a team, to really bond as a team, to command that team, is one of the most rewarding things that you can ever do. So it most definitely is enjoyable and something that I’m very lucky and very proud to have the opportunity to do.

HMCS Whitehorse in home waters off the coast of Victoria, BC. The ship is based out of CFB Esqimalt. (Wikipedia)