(Volume 24-05)

By Colonel (ret'd) Pat Stogran

In my last article (in Volume 24 Issue 3, April 2017), I discussed the concept of Clauswitzian “Centres of Gravity” (CofGs) in the campaign design process. While I did not offer a strict definition per se, I pointed out that the commonly held interpretation is that of the aspect of a force, organization, group or state’s capability from which it draws its strength, freedom of action, cohesion or will to fight. I argued that the relevance of the concept is not so much in its precise definition, but rather how it fuels the creative process of campaign design, a highly subjective process that I believe is the essence of command genius.

Numerous methods have been proposed of analysing CofGs in campaign design, but Dr. Joe Strange, a professor with the United States Marine Corps War College, offered a theoretical framework that I think is very instructive. Dr. Strange argues that CofGs are dynamic, positive, active “agents” in the physical and moral domains that our enemies can use to their distinct advantage in bringing harm to us. In the physical domains these agents are things like groups, military formations or individuals. In the moral domain they may be less tangible, but they should be, nonetheless, readily discernible given a deep enough understanding of the threat.

And while Dr. Strange agrees that it is useful to consider CofGs at the strategic, operational and tactical levels as a means of dividing and defining a continuum of warfare, he adds that it is wrong to limit the number of CofGs at any level, to expect that a CofG conceived at one level could not be manifest at another, or to think that CofGs might not be subject to change.

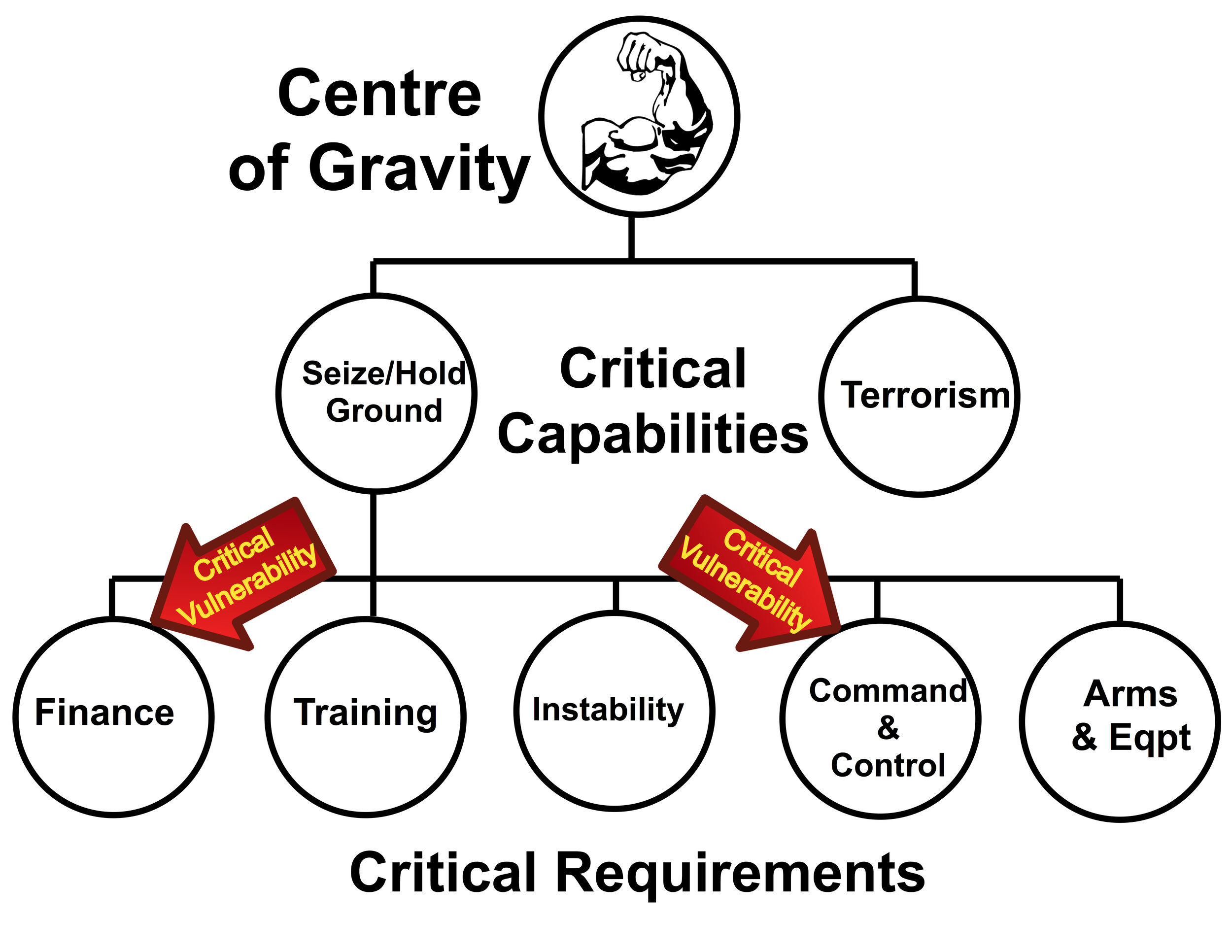

This is where Dr. Strange’s CofG analysis protocol becomes really useful, in my opinion. Clearly, the reason why CofGs are relevant is because of the threat they pose to us. How those threats manifest themselves physically, how the enemy can attack us, is what Dr. Strange refers to as Critical Capabilities (CCs). Theoretically, the difference between a CofG and CCs is that the former would be described as a noun, and the latter as a verb. Any given CofG will most likely have several of these CCs. In turn, each CC requires certain conditions in order to be effective, which Dr. Strange labelled appropriately enough as Critical Requirements (CRs). He defined CRs as conditions, resources and means, and would normally be described with the use of a noun. After all that analysis is done, the planners identify Critical Vulnerabilities (CVs) or CRs that, if decisive actions are taken against them, would serve to defeat or neutralize the enemy’s CofG.

Dr. Strange posits that there are three principal ways of defeating or neutralizing a CofG: make it irrelevant, strip it of the support it needs to be successful, or exploit its systemic weaknesses. In my opinion, this is the essence of manoeuvre warfare (MW) theory. The strategy of making CofGs irrelevant is often called dislocation.

In the theory, there are two types of dislocation: positional and technical, which are best illustrated by a physical CofG at the operational/tactical level. Let’s assume that a commander determines that the enemy’s CofG is an armoured formation being held in reserve. Dislocating it “positionally” would be achieved by causing the enemy commander to deploy the reserve prematurely to an area that would prevent it from interfering with the friendly force’s main effort. Dislocating it “technically” could be achieved by electronic warfare at a crucial time to prevent it from being launched at the key moment.

Another manoeuvre technique is disruption: the attack of CVs where a friendly force can generate overwhelming superiority to strip certain CRs from the enemy’s CofG. On the ground, this could be interpreted as destroying soft targets such as the fuels supplies, stripping it of supporting fires, direct action against command nodes, or other ways of breaking up the cohesion of its battlefield operating systems rather than engaging in a battle of attrition against the armoured reserve force itself.

War is about time and space, and imposing delay on the armoured reserve can be just as effective at neutralizing a CofG as destroying it, albeit not as permanent, but less dangerous and costly. Scatterable mines, destroying bridges and setting up ambushes along counterattack routes to delay the ability of the armoured reserves to interfere with our intended main effort may be all that is required in order to be decisive.

Two other manoeuvre techniques are deception and simultaneity. Sun Tzu said that all war is deception. What you can see can certainly hurt you, but what you don’t see can certainly hurt you more. Simultaneity is a label for the proverbial “horns of a dilemma,” or several dilemmas. The aim is to prevent the enemy from timely action, reaction or counteraction by fooling them into making a wrong decision of when or where to deploy their CofG, or overwhelming their decision cycle and impeding their ability to make the decision to launch at the right time.

Dr. Strange has reverse-engineered several historical battles to illustrate his theory, which is very compelling, but a little too simplistic. In theory, Dr. Strange’s methodology breaks down into a simple flow chart (see diagram on previous page). In practice, however, it ends up being a tangled, complicated web — a system or systems with lots of overlap, nuance and contradiction. Consequently, the analysis can be so convoluted and time-consuming that it takes on a life of its own and becomes of limited use on the ground in the face of the enemy. The problem becomes, however, how to engineer them in the first instance in the face of a living, breathing, proactive and evolving enemy.

And then, on top of the complexity of manoeuvring combat elements in the battle-space you must mobilize the other instruments of power such as diplomacy and economic, social and cultural leverage. It was hard enough for us to coordinate a whole-of-government effort in Afghanistan; the problem becomes much more acute when a campaign becomes multinational, interdisciplinary, interagency — government and non-governmental — and even inter-faith. These complications, particularly that last element alone, might make it impossible for us to ever come up with a coherent campaign plan to keep Canadians safe at home and abroad, not to mention bringing peace and stability to the region.

Importantly, with all the ulterior motives that exist and manoeuvre techniques being employed by the bad guys and certain coalition partners and allies in the region, is it possible that Canada may be aggravating our security situation by being an unwitting contributor to those less-than-apparent agendas?

As usual, I look forward to hearing from Esprit de Corps readers, and will send out a copy of my book Rude Awakening: The Government’s Secret War against Canada’s Veterans to the person that contributes a comment, critique or idea that I can use in an upcoming article.