By Jon Guttman

Of all people, John O’Neill should have known better. As a member of the Fenian Brotherhood, an organization of Irish-American nationalists formed in the United States, he had already led two incursions into British North America, with the objective of seizing some real estate and a major city or two, and then ransoming it in exchange for an independent Irish republic. Neither had worked out, and yet here he was in 1871, trying once more. Perhaps third time would be the charm?

The first time, O’Neill led about 800 men from Buffalo, New York across the Niagara River to occupy the town of Fort Erie on June 1, 1866. The next day he and 650 fellow expatriates, all seasoned Civil War veterans, routed some 850 inexperienced militiamen at Ridgeway. By June 3, however, the Fenians found themselves cut off, their ranks eroding from desertions and as many as 5,000 Canadian reinforcements on the way. O’Neill withdrew to New York, only to find U.S. government men waiting to arrest him for violating the Neutrality Act of 1818.

Soon released from prison, O’Neill was fêted in Fenian circles as the hero of Ridgeway — a battle gloriously won amid a campaign ignominiously lost — and promptly set about planning another invasion. On April 28, 1870 he gathered supporters in Franklin, Vermont, from which he led part of a two-pronged thrust into Quebec Province on May 25, moving on the towns of St. Jean and Richmond, downriver from Montreal and within reach of important railways.

If the first Fenian raid of 1866 was far-fetched, the odds against success in 1870 had only grown. For one thing, the authorities knew of the plan as early as February because, unknown to O’Neill, the fellow Civil War veteran in charge of his munitions, Colonel Henri Le Caron, was actually Thomas Willis Beach, an English spy. Moreover, the Fenians were not invading British North America anymore. As of July 1, 1867, it was the Dominion of Canada, with its own parliament and prime minister — and militiamen who, learning from their humiliation at Ridgeway, were better prepared, trained and were fighting not just for their homes, but also for their own nation.

As he neared the border, O’Neill was twice intercepted and urged to stop by George P. Foster, the U.S. Marshal for the district of Vermont. O’Neill ignored him and led his 400 men into 680 waiting militia at Eccles Hill — who sent them reeling back into Vermont with five dead and 20 wounded. The Canadians suffered no casualties. The third time Foster encountered O’Neill, he arrested him.

The other prong of the invasion, led by Colonel Owen Starr from Malone, New York to Holbrook’s Corners along the Trout River on May 27, fared little better. Counterattacked by 1,030 Canadian and British troops, the Fenians lasted just minutes before conducting an orderly retreat across the border — and then scattered to evade the American authorities. Starr was caught and gaoled in Auburn, New York.

Sentenced to two years’ imprisonment in July, O’Neill was pardoned by President Ulysses S. Grant and released in October. At that point one would think he would have had his fill of filibustering to the north — as indeed the Fenian Brotherhood itself had. O’Neill, however, merely shifted his sights to a new target…and new allies. In 1871, he went west to court the half-blood Métis of Manitoba.

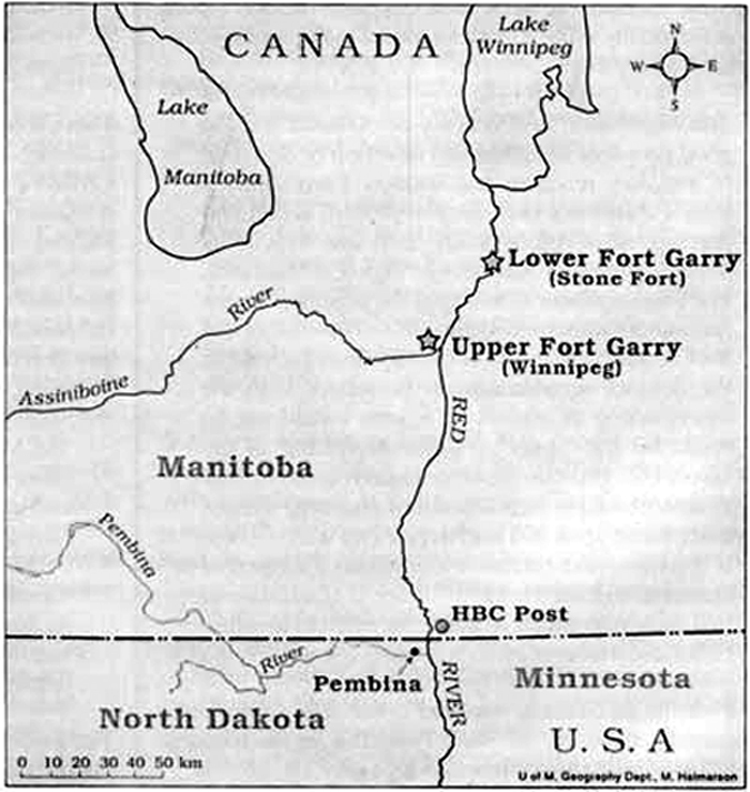

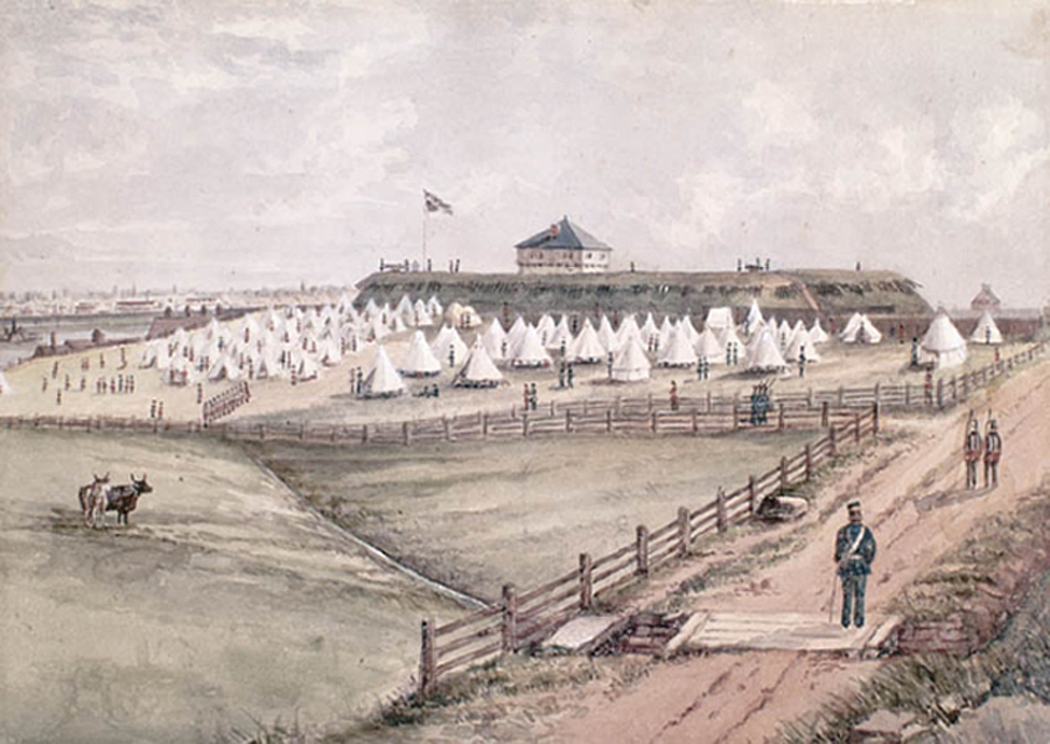

The products of more than a century of predominantly Franco-Indian intermarriage, the semi-nomadic Métis often found themselves as much at odds with the westward advance of Anglo-Canadian settlement as were the First Nations. They inhabited the Red River Settlement in Rupert’s Land, a territory constituting a third of modern Canada’s land mass, which since 1670 had been administered exclusively by the Hudson’s Bay Company — until November 19, 1869, when Canada purchased it from the company for 300,000 pounds ($15 million). In August 1869, when the Canadian government began surveying the region in anticipation of its future incorporation, Métis spokesman Louis Riel denounced its efforts. After Ottawa appointed the virulently anti-French William McDougall as lieutenant governor of Rupert’s Land and the North-West Territories on September 28, 1869, Métis in the Red River Settlement began disrupting the surveys in October. On November 2, 400 Métis seized Fort Garry, where they established a provisional government on the 23rd.

In mid-December Métis leader Louis Riel sent Ottawa 14 conditions under which his people would submit to union, including a bilingual legislature and chief justice, land rights, the establishment of French-speaking schools and the protection of Catholic rights. While the Canadian government considered the petition, tensions rose on January 18, 1870, when the Métis arrested pro-English agitators at Portage le Prairie on charges of conspiring to overthrow the provisional government, sentenced 11 to death and executed one, Thomas Scott, by firing squad. In May Canada dispatched a 1,000-man expeditionary force commanded by British Colonel Garnet Wolseley. At the same time, however, most of the Métis demands were incorporated into the Manitoba Act when it was ratified on May 12. In consequence, when Wolseley’s expedition finally reached Fort Garry in August, the Métis offered no resistance. Still, with murder accusations levelled at him for Scott’s death, Riel slipped away on August 24 to seek asylum in the United States, as did the Irish treasurer of his provisional government, William O’Donoghue.

Born in County Sligo in 1843, William Bernard O’Donoghue had moved to New York after the 1848 famine, but in 1868 was in Canada, teaching mathematics at the college at St.-Boniface. He was studying for the priesthood when he became involved in the Métis cause instead. On November 16, 1869 he was elected representative of St.-Boniface at the first convention of the Red River settlement, subsequently becoming Riel’s treasurer.

O’Donoghue was initially known for a moderate stance, but over the next few months his antipathy toward anything English became more pronounced, causing an ideological rift between him and Riel, whose goal was a just assimilation with, rather than secession from, Canada. After both men fled south, in January 1871 O’Donoghue took a secret petition to President Grant, asking for him to intervene on the Métis behalf in the Red River region. When Grant refused, O’Donoghue turned to the Fenians. He got no more than moral support, but he found willing allies in a handful of diehards within the brotherhood, starting with John O’Neill, Thomas Curley and John J. Donnelly. Between them they drafted a constitution for a breakaway state called the Republic of Rupert’s Land, with O’Donoghue as its first president.

Although the Fenian Brotherhood refused to sanction O’Neill’s and O’Donoghue’s scheme, it agreed not to publicly disavow it and to lend some financial aid. With that O’Neill went to St. Paul, Minnesota, to enlist the aid of unemployed workers sympathetic to his cause, and to obtain a promised 250 Springfield rifles converted into breechloaders, courtesy of his old comrade-in-arms Henri Le Caron.

Remarkably, O’Neill was still unaware that Le Caron, aka Thomas Beach, was a double agent who promptly passed on details of this latest conspiracy to Canadian Dominion Police Commissioner Gilbert McMicken. In September 1871 Manitoba’s lieutenant governor, Adams G. Archibald, began mobilizing 1,000 militiamen. On the 11th the U.S. consul in Winnipeg, James Wickes Taylor, sent a recommendation to Washington that U.S. troops be authorized to intervene.

On September 19, orders to be prepared to take action reached Captain Loyd Wheaton, commander of Company I, 20th U.S. Infantry, at Fort Pembina in Dakota Territory. Located two miles south of the border, Pembina’s primary purpose was to help enforce the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie between the Lakota and whites already settled in the region.

Born in Pennfield, Michigan, on July 15, 1838, Wheaton had, like O’Neill, served in the Civil War, rising in rank to colonel in the 8th Indiana Infantry and earning the Medal of Honor at Fort Blakeley, Alabama, on April 9, 1865. The last thing he needed on top of his regular duties was an international incident or a new war. Still, he knew the Fenians’ intentions, their strength and approximately where they planned to strike. The one missing item of intelligence was when.

Meanwhile, O’Neill and his 37 followers set out, blissfully ignorant as to who knew of their plot — which was to say, virtually everybody — and O’Donoghue set out to contact his Métis acquaintances, equally unaware that they had made their peace with Ottawa. After being contacted across the border by Commissioner McMicken, on September 28 Riel had dispatched two Métis to trail and report on O’Donoghue.

O’Neill and his men finally made their move early in the morning of October 5, targeting a Hudson Bay Company trading post and the nearby East Lynne Customs House. Built a quarter mile north of what since 1823 had been British North America’s border with the United States, the post consisted of a store, warehouse, dwelling and a few outbuildings within a rough-hewn log stockade eight to ten feet high, with bastions at its four corners and entrances on the east and north sides.

Arriving at 7:30, the raiders quickly and easily seized their objective, along with about 20 surprised people they encountered there or along the way. Among the captives they locked up was the post manager, W.H. Watt, Captain Wheaton’s wife and a U.S. Army soldier accompanying her… as well as a small boy who managed to slip out of the building and ran off to Fort Pembina.

It did not take Lieutenant Governor Archibald long to learn of the raid, and he responded swiftly, dispatching Major Acheson Gosfort Irvine southward at the head of 80 militia and scouts. Marching overnight through rain and mud, the Canadians were keen to make short work of this latest invasion threat, but they were in for a disappointment.

At Fort Pembina the youthful escapee told Wheaton of the takeover of the Hudson’s Bay post and customs house. By 11 a.m. that morning the captain had assembled 30 soldiers to be transported aboard wagons, along with a surgeon in an ambulance and a cannon. Hastening to the scene he encountered no resistance. In an October 17 interview in St. Paul published in The

Pioneer, O’Neill explained that when he found himself under assault, “I had fought too long under the Stars and Stripes to want to fight United States troops, whether they had crossed the line legally or illegally.” Instead he and his men tried to flee north, but he and 10 followers were caught.

At 3 p.m. Wheaton, his troops and their prisoners arrived back at Fort Pembina, from whence he dispatched a message to Consul Taylor in Winnipeg: “I have captured and now hold General J. O’Neil [sic], General Thomas Curley and Colonel J.J. Donley [sic]. I think further anxiety regarding a Fenian invasion of Manitoba unnecessary.”

Meanwhile, William O’Donoghue was also making his way north to seek succour among the Métis — only to be captured by them and turned over to Captain Wheaton.

All this was unknown to Major Irvine and his column in Manitoba as they reached Camp St. Norbert on the night of October 7. At 3:30 a.m. he wrote a request for at least 150 trained reinforcements. It was only later that morning that he and his weary troops were stopped at Crooked Rapids and, somewhat to their chagrin, ordered to turn back after post manager Watt’s letter reached the authorities, notifying them the crisis had passed. Canada had repulsed its last foreign invasion without even meeting the enemy.

As late as October 17, O’Neill was bitterly declaring: “I believe the action by Colonel [sic] Wheaton to be completely unauthorized, in crossing into British territory and arresting anyone. Nor do I believe his conduct will be sanctioned by either the department commander, or at Washington. He went upon British territory and ordered his men to fire, and they did fire several volleys … Had there been anyone killed, I have no doubt that he would have been guilty of murder.”

Aside from his refusal to accept that the territory he planned to invade was no longer British, O’Neill had failed to keep abreast of local developments. In May 1870 a survey team from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, engaged in literally straightening out the long-disputed border with Canada, had redrawn the line, placing the Hudson Bay post three-quarter of a mile south, in Dakota Territory. O’Neill and his Irish-American raiders had invaded their own country!

This led to the final anticlimactic twist to the farce. On October 7 the conspirators appeared in court on charges of violating the neutrality laws, only to see the case thrown out for lack of solid proof of their intentions…after all, they had not set foot on Canadian soil. Upon learning of that, U.S. Secretary of State Hamilton Fish demanded that O’Neill be brought to account, and when he returned to St. Paul he was arrested again on October 16 — only to be released soon after by the court commissioner, due to lack of evidence and on grounds of double jeopardy.

William O’Donoghue, who received a Crown pardon in 1877, became a teacher in Rosemount, Minnesota, but died of tuberculosis in St. Paul on March 16, 1878, at age 43. John O’Neill, finally deciding that his third campaign north of the border would be his last, took up land speculation in Holt, Nebraska, helping Irish immigrants to set up farms in the area. It proved to be the greatest success of an eventful but short life, for he died of a paralytic stroke on January 7, 1878 — less than two months before O’Donoghue — also aged 43. His name lives on outside of Fenian circles because his last hometown was renamed in his honour: O’Neill, Nebraska.