By John Guttman

On July 1, 1867, the British colonies of Upper and Lower Canada, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick became the autonomous Dominion of Canada, a confederation of four provinces, to which six more provinces and three territories would be added in the century to follow. In contrast to the radical and violent birth of the United States of America, Canada’s independence had come peaceably through a series of conferences and negotiations. It still recognized Victoria as its queen, but henceforth its affairs were conducted entirely by its own parliament and its own elected prime minister, the first of whom was Sir John A. Macdonald.

Thirteen months before the dominion’s formation, Canadians had found themselves defending their home soil against a bizarre pack of foreign invaders. In June 1866 the Fenian Brotherhood, an Irish nationalist movement based in the United States, tried to stage a multipronged raid into then-British North America, seize a significant tract of land and major cities, and then ransom them back to Great Britain in return for an independent Irish republic.

However unrealistic their scheme seemed even at the time, the Fenians counted — wishfully, it turned out — on the United States offering tacit support or at least looking the other way. As things turned out, the U.S. government was prepared to do neither — in spite of their strained relations during the recently concluded Civil War, Britain had consented to discuss monetary restitution for the damage six British-built commerce raiders had done to the U.S. Merchant Marine. The administration of President Andrew Johnson was loathe to jeopardize the arbitration (which would ultimately be resolved in 1872 with a $15.5 million settlement). Another factor lying more in the Fenians’ own hands lay in the prospective raiders being hardened veterans whose recent wartime experience in the American Civil War, wearing both blue and gray, had sometimes been against each other. In contrast, the militia defending British North America had little to no training and had never fired a shot in anger.

As it transpired, the Fenian invasions of 1866 proved of scant avail to a cause undone from the start by factional differences. On April 14, 1866, John O’Mahony’s faction landed on Indian Island with hopes of seizing Campobello Island, New Brunswick, as a naval base, only to be driven off three days later. All that the premature move accomplished was to let the cat out of the bag.

On June 1, some 800 Fenians commanded by Colonel John O’Neill staged through Buffalo, New York to cross the Niagara River and seize the town of Fort Erie. The next day, at Ridgeway, some 650 of O’Neill’s veterans took on 850 green Canadian militiamen and, after 90 minutes of reasonably matched gunplay, took advantage of a moment of confusion in the Canadian ranks to rout them from the field with a bayonet rush.

This left the Fenians victors in the only sizeable battle of the invasion, but by day’s end, O’Neill realized his position was untenable. His raid across the Niagara had been meant as a feint to draw militia units away from key targets such as Toronto and Quebec, but none of the other invasions had come off. The U.S. Navy gunboat Michigan, two tugboats and a revenue cutter had cut him off from supplies and reinforcements. Furthermore, his own ranks were being depleted by desertions and with 5,000 more Canadians reportedly closing in, he and about 850 followers withdrew to Buffalo on June 3 — to find American authorities waiting to arrest them.

In a belated anticlimax, on June 6 Major General Samuel B. Spiers led about 1,000 Fenians into Quebec to occupy Pigeon Hill, Frelighsburg, St. Amand and Stanbridge. A small local militia force wisely withdrew, but on June 8 Canadian reinforcements arrived and the Fenians pulled back — to find their camp near St. Albans, Vermont occupied by the U.S. Army. On June 9 the Fenian Council of War ordered all remaining troops to stand down.

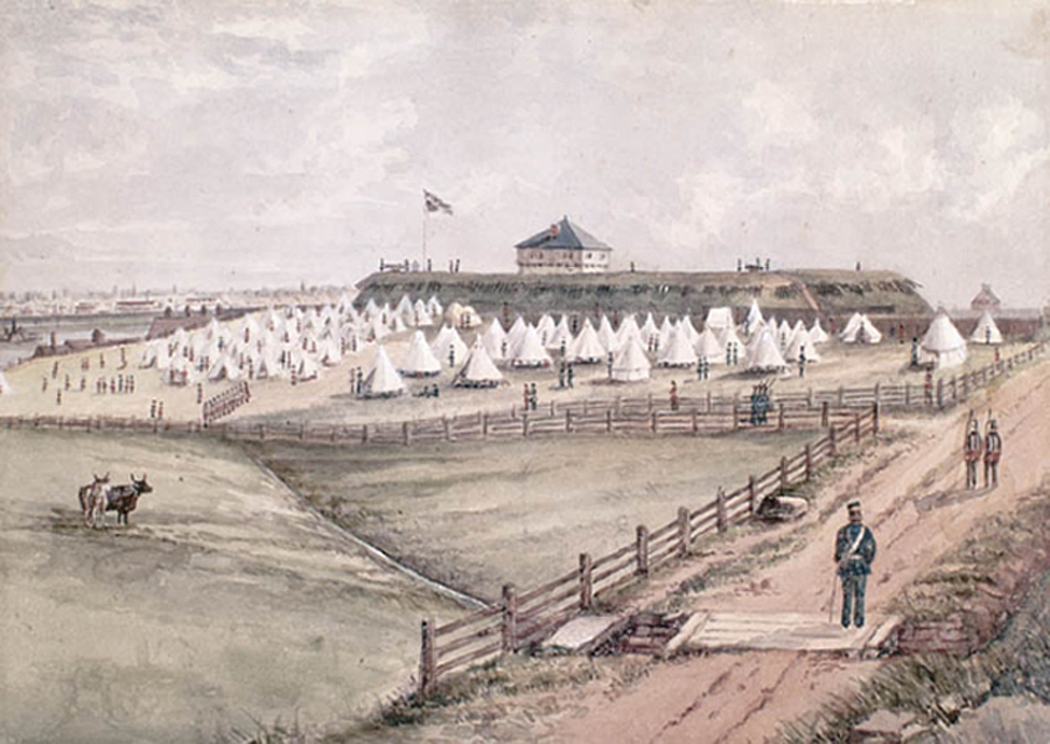

The first Fenian invasion was over, but it had had some influence on the British decision to let a confederation of Canadian provinces proceed on its own. The embarrassing defeat at Ridgeway had also alerted Canadians and British alike to the need for reforms and improvements in the militia. When initiated in 1855 in response to signs of hostility along the border with the United States, the Militia Act had authorised the formation of 11,000 part-time infantry, cavalry and artillery soldiers for local defence. A penurious government had provided the militia with limited resources, however.

When it engaged the Fenians at Ridgeway, The 2nd Queen’s Own Rifles were equipped with modern Spencer seven-shot repeaters, but had never fired them and carried only 28 rounds per man. Under the circumstances, the only surprise was that the militia, cleaving to what drills they had undergone, maintained battle order as long as they did. In the years following Canada’s formation, the training regimen was improved to deal with the realities of possible future combat. Whether any of them knew it or not, this was about to pay dividends, because the threat south of the border had not completely abated.

Since the failure of its first invasion the Fenian Brotherhood’s schism had become more pronounced, with most of its leadership favouring the pursuit of an independent Irish republic by other means. Among those still steadfastly in favour of invasion was John O’Neill. Arrested upon his return to the U.S. but paroled soon after, he had emerged from the debacle as its hero, leading to his appointment as Inspector General of Fenian forces, and on January 1, 1868, as the brotherhood’s president. Over the next two years, however, he came into conflict with the Fenian senate. Amid the intrigues and in-fighting, O’Neill seems to have regarded another invasion as a welcome return to action that might restore his political fortunes. By April 16, 1870, he had convinced enough followers to hold a council of war in Troy, New York, and on April 28 he had mobilized a few hundred men at Franklin, Vermont, for a renewed raid.

Delays in the arrival of what he considered an adequate force robbed O’Neill of his chance to make a grand entrance on May 24, Queen Victoria’s birthday, but the next day he and about 400 men advanced toward the towns of St. Jean and Richmond, both downriver from Montreal and within reach of important railways. As O’Neill neared the Quebec border, George Perkins Foster, a former Union Army brigadier general who had been appointed U.S. Marshal for the district of Vermont by President Ulysses S. Grant on January 24 that year, intercepted him.

Foster told O’Neill that the president — acting with more alacrity than Johnson in 1866 — had issued a new neutrality proclamation two days earlier and would not tolerate any act of Fenian aggression. O’Neill ignored him but Foster confronted him a second time to warn him that spies and informers had already made Fenian plans clear to British and Canadian officials, who had stationed riflemen near the border at Eccles Hill. Again, O’Neill pressed on.

Waiting along Eccles Hill, true to Foster’s warning, were 680 militia, consisting of a detachment of the 60th Missisquoi Battalion, elements of the Dunham Volunteers and a local unit called the Home Guard under the overall command of LCol. Brown Chamberlain. The Canadians had, in fact, known of O’Neill’s invasion plans since February from intelligence sent them by the Civil War comrade-in-arms he had placed in charge of his munitions, Colonel Henri le Caron — who in reality was English-born Thomas Willis Beach, a paid spy.

As the invaders stepped onto Canadian soil the militia opened fire, immediately killing John Rowe and wounding two others. In spite — or, just as likely, because — of their Civil War experience, many of O’Neill’s troops broke into a retreat that degenerated into panic, encouraged by Colonel le Caron, a.k.a. double agent Beach. After vainly trying to stem the rout, O’Neill retired to Vermont and was in a carriage looking for wounded and missing men when he again encountered Marshal Foster. This time Foster was there to arrest him and had him jailed in St. Albans, Vermont.

Patrick O’Brien Riley and Samuel Spiers persuaded some Fenians to hold their ground, but the Canadians kept up their advance, maintaining a continuous fire with their Ballard rifles and Snider breechloaders. The Fenians had set up a cannon in a flanking position, but a charge by a battalion of volunteer cavalry led by LCol. William Osborne Smith overran the position and captured the field piece. By 1800 hours, the last Fenians were gone, leaving behind only Rowe’s body but suffering a total of three dead and 20 wounded, of whom two more subsequently died of wounds. The Canadians, whose ranks had included Victoria’s son — and future governor-general of Canada — Prince Arthur, had won the day without a single casualty.

Meanwhile, more invaders gathered at Malone, New York. These were to have been commanded by Brigadier General John H. Gleason, but on April 26 he was replaced by Colonel Owen Starr, another veteran of the Civil War and the first Fenian raid. At 0700 on the morning of May 27 he led his force across the Trout River to Holbrook’s Corners, 20 kilometres north of Malone and 15 kilometres west of Eccles Hill. There he established a sound defensive position with breastworks along a local post and rail fence and his right flank anchored along the Trout River.

Major Francis Whyte, commanding the 225 militiamen of the 50th Canadian Battalion, “Huntingdon Borderers,” was considering falling back from nearby Huntingdon to Port Lewis when Lieutenant William Butler, intelligence officer for the British 69th Regiment, arrived to announce that he had been scouting the Fenians since 0400 that morning and that reinforcements were on the way. In addition to the 275 men of the Montreal Garrison Artillery coming from Port Lewis, there were 88 Montreal Engineers, troops of the 51st Battalion, Hemmingford Rangers, 100 troops of the Beauharnois 64th Voltigeurs Canadiens, and 45 regulars from a company of Her Majesty’s 69th, led by Colonel George Bagot.

Upon his arrival Bagot took charge of the 1,030 troops at his disposal and laid plans for dealing with the invaders. He dispatched the Montreal Garrison Artillery to Hendersonville to flank the Fenians; the rest would attack directly. Heading that formation, the vanguard of the 50th advanced to 300 yards of the Fenians and deployed for a frontal assault. As one witness described the scene as the Canadians emerged from the woods and advanced, “it was not an intermittent fire, but one continuous fusillade.”

Starr ordered his men to hold their position for 10 minutes and for several minutes the Fenians stood fast. As the Canadians got around their flanks, however, Starr reorganised them to conduct an orderly fighting retreat until they crossed the border, at which point most broke and ran — less concerned about capture by the Canadians than by the American authorities. Starr himself vanished but was soon found, arrested for violation of the neutrality laws and imprisoned in Auburn, New York.

The Fenian invasions of 1870 showed how much Canada’s militia had learned since their shaky start at Ridgeway, in transitioning from defending their home towns to defending their own nation. In spite of its abject failure, however, the Fenian threat was not quite over. Released from prison after six months, John O’Neill came up with one more invasion proposal in 1871. This time the target would be Manitoba.