(Volume 24-05)

By Jon Guttman

One of Canada’s many distinguished airmen of the First World War, Robert Leckie was born in Glasgow, Scotland on April 16, 1890; his family emigrated to Canada in 1907. When not working at his uncle’s firm, John Leckie Ltd., maker of fishing nets, he developed a passion for tennis.

When war broke out Bob Leckie trained at his own expense at the Curtiss Flying School at Toronto Island, followed by advance training at Chingford, England. On June 16, 1916 his rank of flight sub-lieutenant was confirmed and three days later he was posted to the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) air station at Great Yarmouth, near Norwich, England. Flying anti-submarine patrols over the North Sea, Leckie gained a reputation for reliability in the most adverse conditions. His greatest claim to fame, however, involved another adversary — Zeppelin airships.

Ferdinand Graf von Zeppelin’s quest to develop a large duraluminium-framed, controllable, lighter-than-air ship finally bore fruit in 1900. By the First World War, Zeppelins had developed into viable reconnaissance platforms and on August 6, 1914 army Zeppelin Z.VI bombed Liège, Belgium. In that same month Konteradmiral Paul Behncke, deputy chief of the German naval staff, proposed bombing Britain and was supported by Grossadmiral Alfred von Tirpitz, who wrote, “The measure of success will lie not only in the injury which will be caused to the enemy but also by the significant effect it will have in diminishing the enemy’s determination to prosecute the war.” Kaiser Wilhelm II finally approved of the plan on January 7, 1915, and on the 19th naval Zeppelins L.3 and L.4 dropped the first bombs on English soil. On the night of May 31 Army Zeppelin LZ.38 was first to strike London.

Although material damage was modest, the very arbitrary nature of the civilian casualties the airships’ bombs inflicted raised public outcries for the government to “do something.” That in turn spurred the British to develop an air defence system that would ultimately incorporate searchlights, anti-aircraft artillery and aeroplanes. It also compelled both the Army and Royal Navy to divert at least some of their aerial assets from the Western Front to Home Defence. In that respect, the “Zeppelin menace” constituted history’s first aerial terror campaign. Moreover, between the morale factor, the occasional damage done and the resources diverted to countering them, the Zeppelins could also lay claim to being history’s first strategic bombers.

At first, operating at high altitudes at night made the airships difficult for Allied aircraft to intercept, but on June 6, 1915, Flight Sub-Lt. Reginald A. J. Warneford flew his Morane-Saulnier L above LZ.37 and destroyed it with bombs over Ghent, Belgium, for which he received the Victoria Cross. A more significant turning point came on September 2, 1916, when Second Lieutenant William Leefe Robinson destroyed the wooden-framed Schütte-Lanz airship SL.11, in flames within sight of London; he also earned a VC. Four more airships fell victim to aircraft by the end of the year, convincing the German army to abandon them in favour of aeroplanes such as the Gotha and Zeppelin-Staaken Riesenflugzeug (giant aeroplane) for attacking Britain. In the German navy, however, airships retained a fanatical advocate in their commander, Fregattenkapitän Peter Strasser, who relentlessly continued dispatching them against British targets. His hoped-for solution to the advances in aeroplane technology was unveiled on March 10, 1917, when the first of a line of high-altitude Zeppelins, L.42, made an inaugural flight to 19,700 feet.

At about that time Great Yarmouth was acquiring a new weapon of its own. On April 13, 1917, Leckie ferried in the first Curtiss H-8 “Large America” 8660, and flew in Curtiss H-12 8666 on May 7. With their original 160-hp Curtiss V-X-X engines replaced with Rolls-Royce Eagles of 250-hp and more to speed along at up to 90 mph, these well-armed, long-ranging flying boats offered fresh opportunities against the “Zepps.”

The first such opportunity arose on May 14, when L.23 and L.22 embarked on a maritime reconnaissance mission. The latter imprudently sent a wireless message upon takeoff, revealing its regular patrol route off Terschelling, located on one of the Netherlands’ West Frisian Islands. This message was intercepted by the British, who notified RNAS Great Yarmouth. At 0330 hours H-12 8666, crewed by Flt. Sub-Lt. Leckie, Flt. Lt. Christopher J. Galpin, Chief Petty Officer V. F. Whatling and Air Mechanic O. R. Laycock, took off to intercept.

At 0445 hours, Galpin spotted an airship and as Leckie took over the controls, he manned the twin forward Lewis machine guns. Leckie closed to 50 yards and Galpin fired a mix of Brock, Buckingham and Pomeroy incendiary rounds into L.22’s starboard quarter until both weapons jammed. Galpin reported that, “As we began to turn I thought I saw a slight glow inside the envelope and 15 seconds later, when she came in sight on our other side, she was hanging tail down at an angle of 45 degrees with the lower half of her envelope thoroughly alight.” L.22, veteran of 81 flights and 11 raids, was the first Zeppelin destroyed in 1917, taking Kapitänleutnant Ulrich Lehmann and 20 crewmen with it.

Unlikely as a flying boat seemed as a “Zepp strafer,” the history in which Leckie took part was repeated a month later. As L.43 — one of the new “Height Climbers” — was covering a minesweeping operation 40 miles north of Terschelling, another Great Yarmouth-dispatched H-12 — 8677 crewed by Flt. Lt. Basil D. Hobbs, Flt. Sub-Lt. Robert F. L. Dickey, wireless operator H. M. Davies and engineer A. W. Goody — spotted it at 0840 hours on June 14. Catching their quarry at a relatively low altitude, the Curtiss attacked from above and sent it down in flames, along with Kapitänleutnant Hermann Kraushaar and 23 crewmen.

As a consequence of these sea encounters, the airships were ordered to conduct reconnaissance flights no lower than 13,000 feet; however, this handicapped their ability to spot submerged U-boats or mines from that height.

Still, Strasser persisted in championing his airships and on July 8, 1918, the first of a new “X” type airship, L.70, emerged from Factory Shed II at Friedrichshafen, with seven engines producing a combined 1,715-hp and an 81 mph maximum speed, also including a 20mm Becker cannon in its arsenal. Strasser was so encouraged by its performance that, on July 18, he approached Admiral Reinhard Scheer with a plan to dispatch three “super Zeppelins” with reduced bomb loads and increased fuel across the Atlantic to bomb port facilities in New York. Scheer returned Strasser’s proposal the next day with a terse penciled response: “R.S., nein.”

On August 5, L.70, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Johann von Lossnitzer with Strasser aboard, led L.53, L.56, L.63 and L.65 on another sally against industrial targets in the British Midlands. Weather conditions — 75 degrees Fahrenheit, 85 per cent humidity and an unprecedentedly low barometric reading of 29.77 — handicapped the raiders’ ascent, while steadily decreasing west winds resulted in their arriving 60 nautical miles from the coast at 1830 hours, while there was still daylight. By then they had only reached 17,000 feet, to which Strasser compounded the danger by sending last orders to his captains by wireless at 2100 hours. At that time the Leman Tail lightship, moored 30 miles off the Norfolk coast, spotted three airships 10 miles to the north and moving west-northwest in V formation.

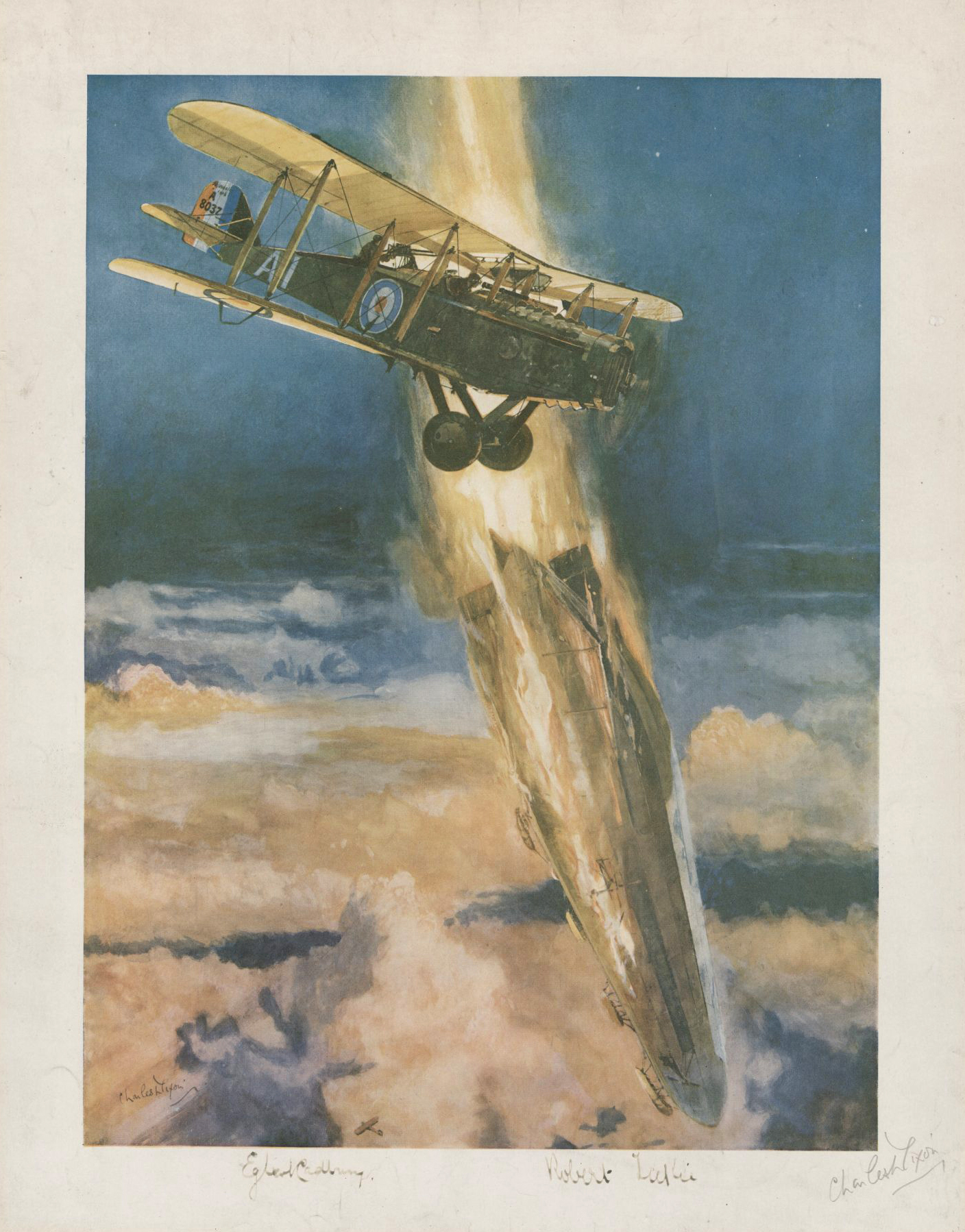

Britain was having a bank holiday weekend and Great Yarmouth was hosting a “grand fête” sponsored by the Royal Navy in aid of the Missions to Seamen when the air raid warnings came in. Within 35 minutes 15 aircraft were either airborne or taking off. Among the first up was Egbert Cadbury, scion of the family of chocolatiers and, like Leckie, already sharing credit in the destruction of a Zeppelin, L.21 on November 28, 1916. Now a major in the Royal Air Force, he commanded No. 212 Squadron (Land Flight) as he climbed into the cockpit of de Havilland D.H.4 A8032. Leckie, also a major and in charge of No. 228 Squadron (Boat Flight), clambered into the observer’s pit behind him. Two 110-lb. bombs were still under the wings as Cadbury hastened skyward at 2105 hours.

Sighting the Zeppelins against the fading twilight, Cadbury pulled his bomb release and climbed to 16,400 feet. At 2220 hours he approached the leading airship head-on and slightly to port so as to “avoid any hanging obstructions.” Leckie’s single Lewis gun lacked sights and his first rounds missed, but he used his fiery Pomeroy ZPT rounds to correct his aim.

“The ZPT was seen to blow a great hole in the fabric and a fire started which quickly ran along the entire length of [the] Zeppelin,” Leckie reported. “The Zeppelin raised her bows as if in an effort to escape, then plunged seaward, a blazing mass. The airship was completely consumed in about ¾ of a minute.”

L.70 fell five miles northwest of the Blankeney Overfalls bell buoy, along with Strasser, von Lossnitzer and 20 crewmen. Meanwhile, Cadbury made for nearby L.65, which had turned east and dumped its water ballast. Leckie fired at it, only to suffer a double feed jam which his hands — in minus-60-degree temperatures at that altitude — were too frozen to rectify. Cadbury raised the D.H.4’s nose to bring his twin Vickers into play, but just then his plane stalled. The four remaining airships returned home, having landed no bombs on England, but at least having survived.

Returning through 12,000 feet of cloud at night, “Bertie” Cadbury had a terrifying half hour until he spotted rows of lights pointing inland from Hunstanton and landed at Sedgeford — followed by the horror of discovering that his bombs had failed to release. Both he and Leckie were gazetted for the Distinguished Flying Cross on August 21.

Other participants in the action were less fortunate. D.H.9 D5802, crewed by Capt. Douglas B. G. Jardine and Lt. Edward R. Munday, put some 340 rounds through L.65’s rear gas cell before it climbed away, but they subsequently crashed in the sea, as did Lt. George F. Hodson in a Sopwith 2F1 Camel. All three men drowned. Additionally, Lt. Frank A. Benitz of No. 33 Home Defence Squadron, in Bristol F.2B C4698, crash-landed at Atwick aerodrome. He and his observer, 2nd Lt. H. Lloyd-Williams, were both badly injured and Benitz died the next day.

Strasser’s Zeppelin bombing campaign against Britain literally died with him in a suitably Wagnerian finale. In retrospect, Cadbury was glad that L.53 and L.65 got away, regarding their destruction as unnecessary overkill. As Leckie put it, “We accomplished our object in that the shooting down of L.70 put an end to the Zeppelin raiding of England.”

Of a total of 115 airships produced during the First World War and employed on all fronts, 53 were destroyed and 24 too badly damaged to remain operational, an attrition rate of 40 per cent. Bob Leckie, involved in the destruction of two of them, later wrote a succinct requiem:

The lesson of the airships is plain for all to read. The Germans had in their possession the most effective vehicle for fleet reconnaissance in any power’s hands at that time. It was, at the same time, just about the world’s worst strike aircraft!

After the war Leckie commanded 1 Canadian Wing on April 2, 1919. He subsequently directed flying operations on the Canadian Air Board and overseeing the development of postal and commercial air services throughout the country. Rejoining the RAF in 1922, Leckie served at the Naval Staff College and Coastal Command headquarters, also marrying an American girl he’d met on the voyage to Britain. His many interwar positions culminated in RAF Commanding Officer for the Mediterranean from Malta, but much to his subsequent regret he was recalled to Canada before things heated up there.

In February 1940 the British Air Ministry appointed him Air Member for Training in Canada — superseding Royal Canadian Air Force Headquarters — with the rank of air commodore. He took up that somewhat touchy duty in February 1941 and was subsequently promoted to acting air vice marshal. In 1942 he transferred to the RCAF, rising to chief of the air staff with the grade of air marshal on January 1, 1944. After retiring from the RCAF in on September 1, 1947 he played an active role in the Canadian Air Cadet League. A Companion of the Bath with the Distinguished Service Order, Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross and Canadian Forces Decoration, Bob Leckie died in the Canadian Forces Hospital, Ottawa, on March 31, 1975, just 16 days short of his 85th birthday.