(Volume 24-06)

By Robert Smol

Early in the morning on June 26, 1917 a train from New York arrived in Montreal. Among the passengers on that train were several recruits, mostly American, who had joined the Canadian Army through its recruiting centre in that city. Among those new recruits was 24-year-old Thomas Dinesen, a Danish engineering graduate who was desperately looking for a chance to make his mark in the war.

He succeeded. Just over a year later Dinesen, who joined the Canadian Army before entering Canada and as a recruit could barely speak English, would be awarded the Victoria Cross at the Battle of Amiens. He would also earn the French Croix de guerre.

Part of the citation for his VC reads: “five times in succession he rushed forward alone, and single-handed put hostile machine guns out of action, accounting for twelve of the enemy with bomb and bayonet. His sustained valour and resourcefulness inspired his comrades at a very critical stage of the action, and were an example to all.”

By the time the war ended Private Thomas Dinesen VC had become a lieutenant. Returning to his native Denmark at the end of hostilities, he went on to a career as a novelist and, in 1929, wrote Merry Hell, one of the first Canadian memoirs of the war. To the historian, Merry Hell serves as a candid account of the life of a common soldier in training and in battle. The memoir also serves as a frank critique of the administrative and training shortcomings that continued to pervade the Canadian Army throughout the war.

Thomas Fasti Dinesen was born into a wealthy aristocratic family in Rungsted, Denmark on August 9, 1892. His older sister was the famed novelist Karen Blixen, whose award-winning stories, such as Out of Africa, have been adapted to film. While studying engineering at university, Dinesen served in the Danish Army reserve. Graduating from university in 1916 and frustrated at his country’s neutrality, Dinesen unsuccessfully sought to join the French and British armies. Refusing to give up, he then travelled to New York hoping to enlist in the U.S. military, which seemed poised to enter the war. Here too his hopes were dashed when the government chose only to enrol American citizens. As fate would have it, Dinesen happened to then stumble on a recruiting centre that the manpower-starved Canadian Army operated in that city.

And so it was that Dinesen found himself on his way to Montreal to train as a recruit in the 42nd Battalion (The Royal Highlanders of Canada, the Black Watch). At first his limited English and unfamiliarity with Highland traditions presented somewhat of a culture shock.

“I spent the whole first day of my military career wondering why our regiment should be named after a black watch.” Yet he found the kilt “pleasantly cool” in the summer heat but was nonetheless relieved that “they have promised us trousers for the winter.” Being an agnostic he narrowly escaped being rejected by the Canadian Army by agreeing to self-identify as a Presbyterian “on account of my kilt, I guess.”

Beginning their training with 2nd Reinforcement Company of the 5th Royal Highlanders, Dinesen and the other recruits were housed in the Guy Street Barracks, which was in an abandoned factory. The quarters were described by Dinesen as “a nasty, musty hole, with dark and narrow corridors; filthy and reeking with coal dust and all sorts of refuse.” Every morning, after inspection, the recruits would march through the city to the grounds in front of McGill University where they would train.

Throughout the first half of his memoir, up to the point he enters the front, Dinesen expressed a profound frustration with the quality and practicality of Canadian Army training. One month into his service he writes: “we are still waiting for the serious part of the work to begin … here the work is mere child’s play.”

One would think that in the aftermath of costly battles such as the Somme and Vimy, some level of operational professionalism would have trickled down to the training establishments in Britain and Canada. Yet as the battle-hardened Canadian Corps, including his 42nd Battalion, was moving from Vimy to attack Hill 70 in July and August of 1917, Dinesen and his fellow recruits back in Montreal were still receiving their basic weapon instruction in the Ross Rifle, which Dinesen described as a weapon “far too dainty for warfare — a mere gun for target practice.” At no point did the training in Canada move much beyond the basic parade square drill, where “all they teach us, day by day is, therefore, the art of presenting arms and banging our rifles against our shoulders in the correct, jerky fashion — is there anything to be gained by this?”

Yet it was during his initial training in Montreal that Dinesen had his first near brush with combat. With the legislation bringing in conscription being hotly debated in Parliament, word came that an anti-conscription mob was planning to attack the Guy Street Barracks.

“Together with a few of the others, I was posted in the office, supplied with plenty of ammunition, with the order to hold the position to the last drop of our blood. The barracks were quickly turned into an impregnable fortress: machine guns were even placed on the roof.” Perhaps thankfully for the Army’s reputation, and the already strained French–English relations, the alleged mob never materialized.

In October of 1917, after only four months in Canada, Dinesen was on his way back to his native Europe, as a kilted Canadian soldier. Yet to his continued frustration, the additional four months of advanced training they were to end up receiving in Britain did not offer much in the way of practical skills that the conscientious Dinesen knew he would need at the front.

“Do they really mean to send us out without teaching us even the slightest preliminaries concerning trench warfare?” he angrily wrote on February 16, 1918 after training in Britain for over three months. “The whole plan of training, as far as I can see, is exactly the same as in pre-war days.”

And then there was the question of time which, according to Dinesen, the Army’s training system seemed to have way too much of in spite of the desperation for trained and reliable reinforcements.

“Our military training leaves much to be criticized,” he wrote on his training near Aldershot on January 14, 1918. The only exception to this was rifle practice, or “musketry,” where “they have given us plenty of time to acquire the art to perfection.”

But other than the time spent on the ranges, the typical day in camp consisted of “P.T. from 7.15 am to 8 a.m.; parade at 8.30 a.m.; drill till noon and again from 1.15 p.m. to 4.30 p.m.; one can’t call that heavy work.”

The conscientious recruit’s frustration at the tepidness and impracticality of the training regime seemed to reach a boiling point when combat skills vital to survival in the trenches, such as handling of Mills bombs, were taught in rigid textbook like fashion without actually going through the motions of handling or throwing an actual Mills bomb.

“We are taken out day by day and lined up on the parade ground and taught exceedingly carefully how to stand in a strange, theoretical position; left foot forward; body curved backwards; right arm, pretending to hold grenade, at backward stretch … It looks quite fine on the parade-ground, but do they really think we are going to act according to these instructions when hurling bombs from a deep and narrow trench — or rushing across No Man’s Land?”

Fortunately his deployment to the Western Front in mid-March 1918 was, at least in his area, a time of relative inaction allowing him time to pick up and learn the routines of trench warfare that were not covered in training.

The action that was to award Dinesen his Victoria Cross took place on August 12, 1918, when the 42nd was conducting mopping-up operations in the Parvillers sector. According to the 42nd Battalion’s War Diary, the battalion had “come into the line with instructions from Brigade to maintain a steady pressure against the enemy who was believed to be fighting a rearguard action.” However, a frontal attack was deemed by the commanding officer of the 42nd as too risky because of the strength of their own wire, which they would have to cross, as well as “heavy enemy entanglements.” Instead, the unit decided to attack the Germans by way of a bombing attack from their northern flank, which another division had recently penetrated.

According to the operations order produced by the 42nd on the morning of the August 12, the battalion’s first objective, once in the German lines, was to mop up the intermediate trench system on the Rouvray-Parvillers Road with their second objective being mopping up the enemy in Parvillers itself. Dinesen’s company was specifically tasked to “bomb down the old German front and support trenches.”

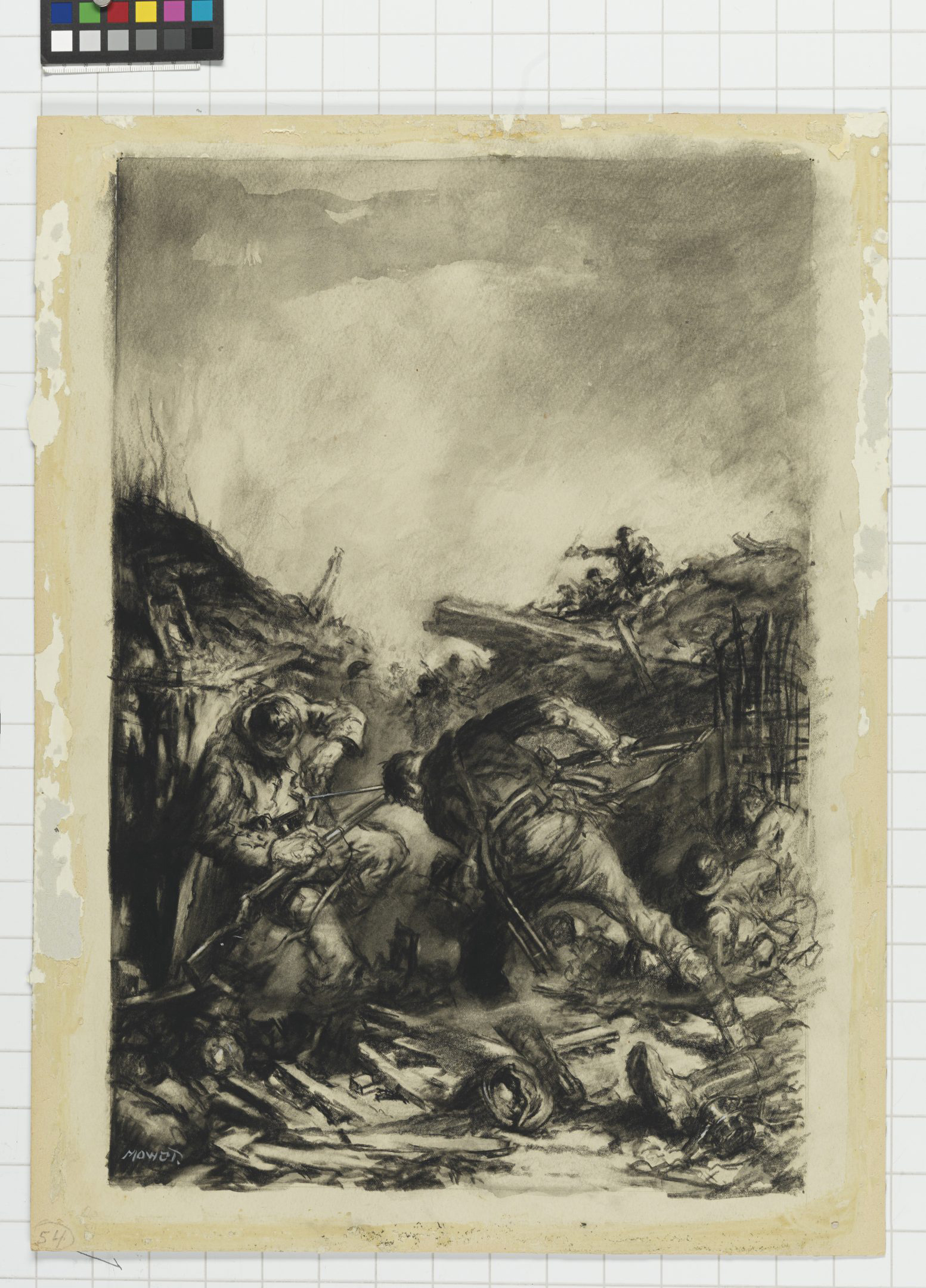

The Germans were hardly demoralized. According to the 42nd Battalion’s report on operations for that day, “strong resistance was encountered and all enemy posts and blocks fought with determination and in many cases the attack was pressed home with the bayonet.”

As his citation reads, Dinesen personally took the initiative on this series of bombing/bayonet attacks on five separate occasions. His recollection, on at least one such occasion, is described in his memoir.

“I turn a corner quickly — two grey Germans stand straight in front of me … Two red flashes straight into my face — done for already! — but they haven’t hit me, so now it is my turn. A snap-shot at one of the two, and the other disappears round a corner … At the next corner a shower of rifle bullets and “sticks” whizz past my head from a machine-gun post … I fire away madly till my magazine is empty; then I fling down my rifle and hurl my bombs at them … and then we reach the next machine-gun post and throw ourselves against it, yelling and roaring, with bombs and bayonets, battle-mad …”

After the Battle of Amiens, Dinesen was promoted to acting corporal and, during the last few months of the war, was selected to undergo officer training. Just prior to the Armistice of November 11, 1918 he received his commission as a lieutenant and was assigned to the 20th Reserve Battalion of the Quebec Regiment until his release in January 1919.

His service over, Dinesen moved to British East Africa (modern-day Kenya) where his sister Karen was already living and had run into trouble with the British authorities because of prior business dealings with a German general. According to Blixen, her brother’s presence with his Victoria Cross and Croix de guerre helped disseminate any lingering animosity the British had towards the family. He was also awarded the Order of Dannebrog from Denmark. In 1923 Thomas Dinesen returned permanently to Denmark and a writing career. He passed in March of 1979.