(Volume 24-6)

By Jon Guttman

Although Britain only committed three squadrons of Sopwith Camels to Italy during World War I, they produced a lot of aces, a disproportionate number of whom were Canadian — starting with William George Barker, whose tally of 43 aerial victories was the highest of any nation’s over that front, and who would subsequently receive the Victoria Cross for engaging 60 German aircraft, of which he was credited with shooting down four, on October 28, 1918. Among the many other Canadians who flew with Barker with their own share of distinction was Gerald Birks, whose 12 credited successes included two enemy aces.

Gerald Alfred Birks was born on October 30, 1894 in Montreal, Quebec. The son of William Birks, owner of the jewellers store Henry Birks and Sons, Gerald was educated at Montreal High School (Junior Section), later attending Lower Canada College, also in Montreal. During part of 1914–15, Gerald was a part-time student at McGill University’s Department of Agriculture, during which, in an intercollegiate ski meet held at Dartmouth, he won two second prizes in cross country and jumping, and took third place in the slalom.

On August 31, 1915 Birks enlisted in the 73rd Battalion of the Black Watch, Royal Highlanders of Canada, and took the Infantry Officer’s Training Course at the Citadel in Halifax, Nova Scotia. During the winter of 1915 and 1916, he trained with the 73rd Battalion in Montreal and at Camp Valcartier, near Quebec City. When the battalion went overseas, however, Birks was left behind because, at 21, he was considered underage. That age standard would soon be revised, but in the meantime Birks used the influence of his uncle, who was the head of the Young Men’s Christian Association in Canada, to expedite matters.

“I proceeded overseas on my own,” Birks said, and found employment driving concert parties and entertainers to Canadian military camps in the Folkstone area for the YMCA. “While in Folkstone,” he said, “I received a telegram from the adjutant of the 73rd Battalion, saying that the colonel wanted me to rejoin the battalion, which I did. Our training continued at Camp Bramshot.”

In July 1916 Birks’ battalion departed Folkstone for Flanders. “We had our first casualties while leaving Ypres at night,” he said. “We were in Belgium and northern France for some time before moving south to the Somme.”

Begun on July 1, 1916 with a mammoth artillery barrage, the Battle of the Somme had been intended as the great breakthrough on the Western Front, but became just another meat grinder for the hapless soldiers who walked across no man’s land to assault the well-entrenched Germans. As his unit was committed to the faltering offensive, Birks said: “I was wounded by two pieces of lead from a German dum-dum bullet which shattered the left wrist of my company commander. When I got to him, he was holding his left hand in his right hand. It looked as if his left hand would drop off if he let go. He was losing blood at a frightful rate. With a knife which I had just received as a Christmas present from my family in Montreal — and which I still have in my trouser pocket — I cut his trench coat, tunic, coatsweater, shirt and underwear until I was able to get my thumb on the artery at his left elbow. I was able to almost stop the bleeding. Because we had been first over the top, the last man in the company caught up with us. I shouted to him to have the stretcher-bearers come back, as the captain had been hit. As they started to climb out of the trench, I could see the blood starting to flow again. Against my will, my thumb was letting go, so I knew that I myself had been hit.”

Birks would spend a month in London hospital recovering from his wound. “When I was about to be discharged from the hospital I applied for sick leave to Canada,” he said. “I thought that there was no chance of my application being granted. But it was granted and I sailed for Halifax and took the train to Montreal.”

While convalescing at home, Birks decided to pursue a new endeavour. “When in France,” he said, “I had talked about transferring to the Flying Corps. Our medical officer said, ‘Gerald, there is no use of you applying for transfer. Your medical card, which I have, shows that you have astigmatism and the Royal Flying Corps will not have you.’”

When Birks returned to Montreal, however, the British military was clamouring for Canadian pilots, so he applied. The recruiter warned him, “You will have to give up your commission in the Canadian infantry to join up as a cadet,” a grade equivalent to a second-class mechanic. “That is all right with me,” Birks replied. “If I cannot earn a commission in the Flying Corps, I do not deserve one.”

Before he could start over again, however, Birks faced a major obstacle. “I had to pass a physical examination,” he said. “The doctor examined me thoroughly and then sent me into the next room to have my eyes tested, which was being done by a corporal. He had me cover one eye and read the test card in which I rated 20 — perfect vision. I covered the other eye and read the card again. Again I scored 20. So both eyes were perfect and I passed, as he did not notice the astigmatism.”

Upon acceptance, Birks reported to the RFC headquarters in Toronto. “I was billeted in a building which still stands on College Street,” he said. “I was made to drill the youngsters in elementary infantry drill. They gave me one stripe — a lance corporal. Then they gave me two stripes — a full corporal. Then they wanted to make me sergeant, but I refused. I felt that a sergeant must cooperate with the officer so much that he ceased to be ‘one of the boys.’”

Birks remembers that, “After ground school I was sent to Camp Mohawk near Deseronto. There I had a total of two hours and 20 minutes before going solo. The two hours included my first flight, when the instructor said: ‘Do not touch the controls. I will show you your flying field, the Bay of Quinty, the town of Deseronto, the railway tracks and a few of the features to the west.’ When I had a total of 35 hours, I was made a flying instructor and sent to Camp Borden, where I instructed all summer. I was posted for overseas on November 16, 1917.”

In England Birks flew Avro 504Ks with “A” Flight, 4th Training Depot Squadron at Hooton Hall. He then moved up to Sopwith Pups and Camels with No. 54 Training Squadron at Castle Bromwich, near Birmingham. “There,” Birks recalled, “the English instructor said to us: ‘You damned Canadians put your machines into a gentle glide and think that you are diving. There are two pieces of canvas laid out in the next field. They represent an enemy machine for you to dive at; now get well over it before you start your dive.’”

And so he did. “When I looked over the target through my sight, I was not diving quite steeply enough. I moved my joystick forward very slightly, but it was enough to make my machine suddenly turn upside down. I was hanging in my belt and the seat cushion was out behind my knees. When I tried to half loop, the elevator slowed up my forward speed and I started to spin on my back, I put my controls into neutral and stopped the spinning.”

Not giving up, Birks attacked the target a second time. “When I tried again, I started to spin in the opposite direction. Then I thought, ‘If I cannot half loop, I will try a half roll.’ By that time the trees below me were coming up very fast. The half roll worked. I was not very far from the tops of the trees. I flew around the airfield several times before landing. I had been with 66 Squadron at the front quite a while before I heard that you can often pull out of trouble by using your engine.”

By the time he was sent to an operational assignment, Birks had the good fortune to have amassed 138 flying hours, including 10 hours 30 minutes on the tricky Sopwith Camel — nearly twice the amount accumulated by most Camel pilots before they were sent to the front.

On March 10, 1918, 2nd Lt. Birks joined No. 66 Squadron which, with Nos. 28 and 45, had been sent to northern Italy following the catastrophic rout of the Italian army at Caporetto on October 26, 1917. “Our field was located in San Pietro in Gu,” Birks said, “east of Vicenza, west of Citadella, between the Brenta and Astico rivers.” The commander was Major J. Tudor Whittaker, who Birks described as “an efficient squadron commander. He had few rules and they were sensible ones. And he was a good sport.”

Birks was assigned to “C” Flight, led by New Zealander Captain John Maxwell Warnock. Other flight members with whom Birks would do much flying in the next few months were 19-year-old Lieutenant William Carroll Hilborn from Alexandria, British Columbia, and 2nd Lt. Gordon Frank Mason Apps from Kent, England.

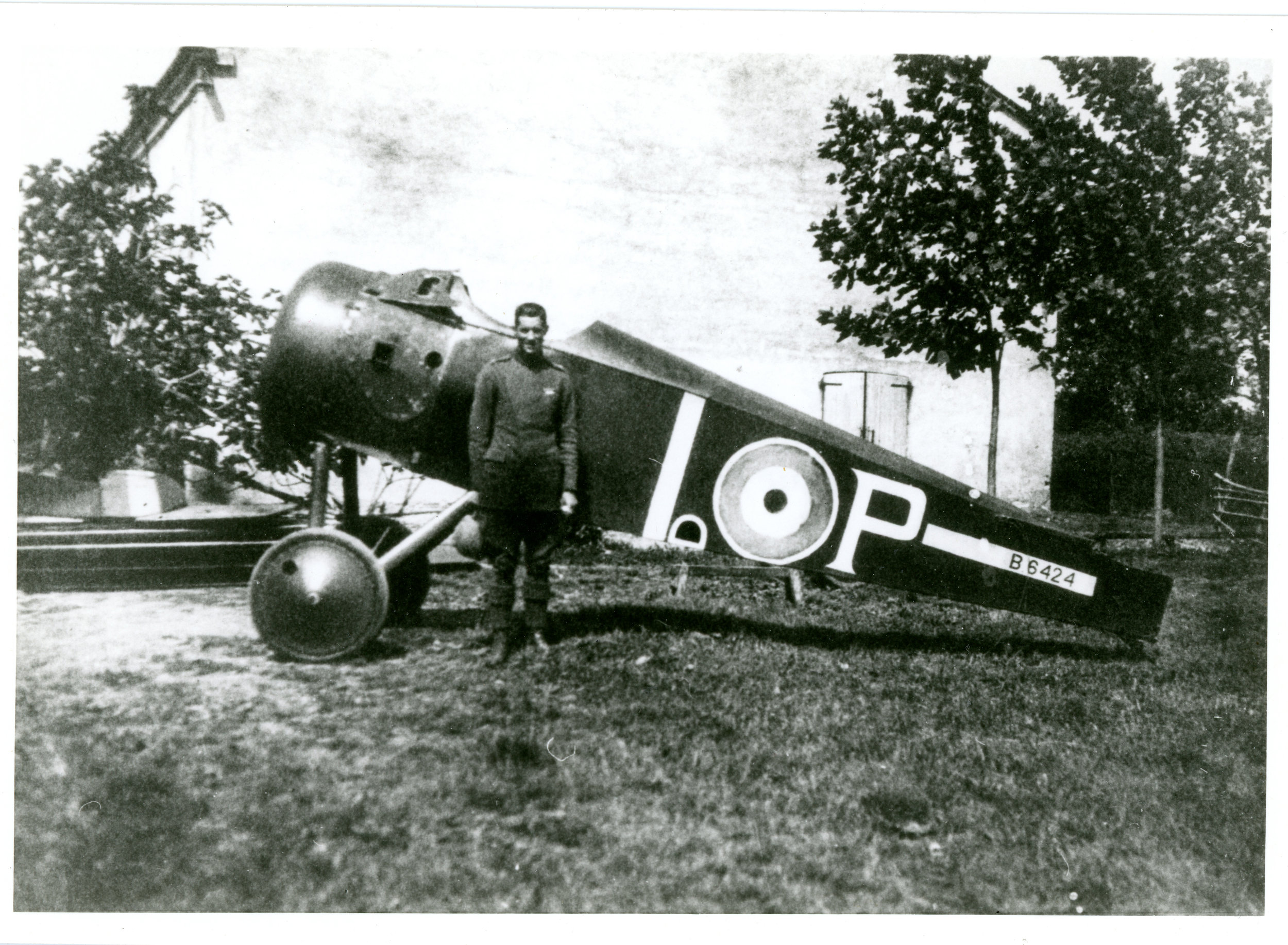

Birks flew five different Camels in his first weeks with No. 66 Squadron, but the one that would eventually be his “personal” plane was B6424, bearing the fuselage letter “P,” which he described as “a true Sopwith (built by the Sopwith Company),” as opposed to one of numerous Camels produced by subcontractors, and had been with the squadron since October 15, 1917. “It had a 130-hp Clerget engine,” said Birks. “It was not new when allotted to me, but it was a very sweet machine to fly.”

On March 18, 1918, Birks and Warnock reported encountering a “Rumpler” over Pravisdomini aerodrome and both attacked. One of Warnock’s guns jammed, but he pursued the descending enemy for 500 feet until he used up all his ammunition in the other weapon, claiming to have seen the observer slumped in the rear cockpit. Birks kept after it to 100 feet, at which point he saw it crash near the aerodrome, to be confirmed as his first victory. In actuality, his quarry was an Austro-Hungarian-built Hansa-Brandenburg C.I, serial number 161.69, of Fliegerkompagnie (Flik) 43/D, whose pilot was wounded. Upon learning those particulars, Birks wrote back: “One thing that strikes me at this time is how very poor our identification of enemy aircraft was. We had very small drawings of the various types of our opposition. My log book states that my first victim was a Rumpler two-seater and my second an Aviatik two-seater. Your list, which I assume is correct since it is based on Austrian records, states that they were both Brandenburg C.Is.”

Birks remembers his first kill. “My first enemy machine, though a two-seater, had only the pilot in it. I did not intend to kill or wound him after he was on the ground, but the bullets from my machine were not going where my sights were pointed. I tried to destroy his machine. But he was hit although a short distance from his craft. After that first patrol, I had my machine put on the target range very frequently.”

Birks’ second victory came southeast of Conegliano on March 24, and was over Brandenburg C.I 69.81, both of whose crew members, Sulski and Poelzi of Flik 50/D, were killed. Again, Birks had been at the controls of B6424, and on March 29 that was officially designated as his regular Camel.

On April 10 Nos. 66 and 28 Squadrons had an exchange of flight leaders, with Warnock transferring to take over “C” Flight at No. 28 while its “C” Flight leader took over No. 66’s “C” Flight. Birks’ new flight leader was Captain William G. Barker. For Birks, this change marked a turning point. Under Barker’s contagiously aggressive leadership, his combat career was about to transition from honourable to downright deadly.