By Commodore (ret’d) Mark Watson

Anyone who has entered a federal building will have undoubtedly seen a security guard wearing either a blue or white uniform asking for identification or performing other security duties. Visitors tend to believe that this individual is a federal employee. In fact, this person is a commissionaire.

While many recognize the organizational name “Commissionaire,” few are aware of its origins and the important role this uniquely Canadian organization has played for veterans, and for Canada, over the last 96 years.

Officially known as Canadian Corps of Commissionaires, this uniquely Canadian, private, not-for-profit organization was founded in 1925 with the purpose of providing meaningful employment to military and RCMP veterans and delivering security services to Canada and Canadians.

To fully appreciate the Corps’ history, one needs to go back to Great Britain in the mid-1850s. The Crimean War—a two-and-half-year military conflict which saw Great Britain and her allies fight against Russia in the Crimean Peninsula and Caucasus—resulted in a large number of veterans. Many of these soldiers were wounded and had a hard time finding employment after returning home to the British Isles. There was no viable government social net for these veterans; they were left to fend for themselves.

Retired army officer Captain Sir Edward Walter recognized the need to right this wrong by providing meaningful employment to these former soldiers who had served so gallantly. He knew that a soldier’s innate discipline, professionalism and training could be tapped to provide oversight of property and other duties

In 1859, Walter arranged for seven disabled veterans to provide security to local businesses in London. Walter wanted to give this group of veterans an appropriate name and looked to France for inspiration. On the continent, attached to every hotel in every large town, were “commissionnaires.” They were responsible for assisting guests in getting baggage safely through customs, running errands and carrying letters.

Not wanting to completely copy the French, he called his new organization the “Corps of Commissionaires,” anglicizing the word “Commissionnaire” by taking out the second ‘n’—Commissionaire. The term “Corps” was included to emphasize the military roots of the employees. The organization adopted a uniform and grew slowly, often calling on wealthy benefactors for support.

The Corps had a close relationship with the British Forces. Many senior military officers noticed and appreciated the distinctive work Walter was doing. One such officer was Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught. He had been the Inspecting Officer for the British Corps’ annual parade in 1904. The image of veterans parading with a new sense of purpose made quite an impression on him, something he carried with him when he became Canada’s Governor General in 1911.

With war raging in Europe, the Duke wrote a letter to the President of Military Hospital Commission in 1915 to suggest that “the formation of an organization similar to the Corps of Commissionaires in Great Britain should be considered” for returning servicemen. However, it was not until in the 1920s, after the Great War had come to an end and brought thousands of injured soldiers back to Canada, that several prominent Canadians, supported by the federal government, created a Canadian version

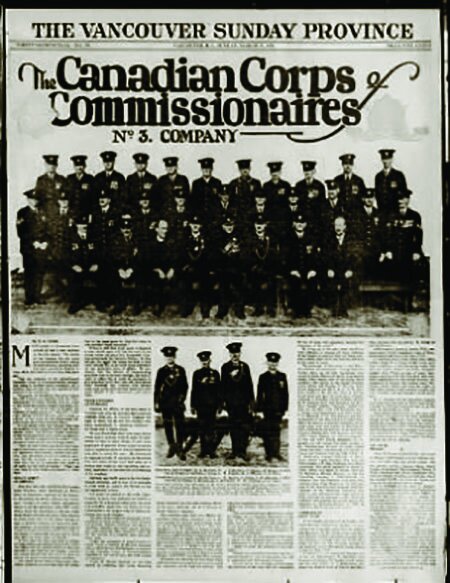

In 1925, a year before the Royal Canadian Legion was founded, five Montreal lawyers united to lay the groundwork for a veteran-centric organization. The five founding members—John MacNaughton, Albert Isidore Livingstone, Joseph Horace Michaud, Philip Meyerovitch, and Max Bernfield—received a Federal Charter on 25 July to find employment for veterans. Another agency was instituted in Toronto soon after. Together they became known as Companies 1 and 2. Vancouver became home to the British Columbia Corps of Commissionaires on 6 October 1927

Unfortunately, there was little cohesion among the Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver groups, and their effectiveness gradually declined until finally, in 1937, the Department of Pensions and National Health, through the Veterans’ Assistance Commission, acquired the private charter and undertook to oversee the formation of the Corps on a national basis. Under the leadership of MGen W.B.M. King, who was appointed the first national president, the Corps finally had the oversight needed to become firmly established. Board members, all former military leaders, volunteered to oversee the Corps and provide good governance.

To highlight the fact that Corps was based on military ethos and linkages, Governor General Lord Tweedsmuir was made the Corps’ first Honorary Patron in 1937, a tradition for Governors General ever since.

By the end of 1937, Canadian Corps of Commissionaires companies had been established in Montreal, Hamilton, Windsor, Calgary, and London. Within two years, there were new operations in Winnipeg, Edmonton, Halifax, and Ottawa. Commissionaires were welcomed everywhere across the country. As the Edmonton Bulletin wrote in 1939:

“In smart blue uniforms with the badges of their Corps on cap and cross-belt, the first unit of the Canadian Corps of Commissionaires in Edmonton is now on duty, and shortly, a night patrol and property protection service will be at the disposal of Edmonton Citizens. The night patrol service carried out under supervision by hand-picked ex-servicemen with the best of records.”

In 1945, with the end of the Second World War in sight, the newly formed Department of Veterans Affairs approved a Treasury Board submission that identified the Corps as an important civilian employer for veterans. The submission explained that:

“Membership in such organisations (the Corps) is limited to men of exceptional character who have had long and worthy records of service in His Majesty’s Forces and who now, to be self-supporting, desire employment in civilian occupations in which personal qualities developed by military discipline and training would be or particular value.”

The Corps received unique recognition not afforded to any other private sector organization. Specifically, the Treasury Board sent a letter to all government departments, stating that,

“The Board considers that there is work in the Public Service of Canada that could, with advantage, be performed by personnel obtained through the Canadian Corps of Commissionaires and requests that all Departments, Boards and Commissions, give consideration to the employment in positions exempted from the Civil Service Act.”

This became known as the Right of First Refusal (RFR), a policy through which Federal Government bodies are required to provision security guard services from the Corps—a privilege that continues to this day—a unique policy which the UK Corps of Commissionaires was never able to achieve. Commissionaires would be found across Canada providing security to federal buildings as a way to provide meaningful employment to veterans, and likely confusing the public into believing commissionaires are employees of the federal government.

The Corps was always there to assist the many Second World War veterans who had difficulty finding jobs in the private sector. Included in the thousands who worked under the Commissionaires’ banner after the war was Collin Borrow, a Victoria Cross winner from the Great War who worked at CBC headquarters, the Don Jail and Sunnybrook Hospital; First World War veteran Hari Singh, one of the first Sikhs to serve in Canada’s military; and Oren Foster who won the MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) for capturing German soldiers during the Second World War. The calibre of people employed by Commissionaires, and their desire to serve, laid the foundation for this strong, national organization.

Between 1945 and 1950, with thousands of veterans returning to Canada following the war, the number of units in the Corps almost doubled. Seven new Divisions were founded including one that covered New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, one in Quebec City, two in Saskatchewan and one in Kingston. The Newfoundland Division commenced operations in January 1950, less than a year after the province joined Confederation.

As the organization grew across Canada, Commissionaires needed to project an image of pride and honour. While there was no direct link to the UK Corps of Commissionaires, it was decided, nevertheless, to adopt a uniform that was based on, but not identical to, its British cousins. This was done largely out of respect for what Captain Walter had started. The new uniform included a blue serge jacket, white cap, white shirt, and a cross belt. Military ranks and military traditions were incorporated into the Corps. This included the acquisition of Corps Colours, regular parades, mess dinners and inspections. An oath of allegiance was adopted based on the military equivalent. Positions were based on military structure with Commandant and adjutants being found in what was then known as Divisions. Commissionaires took pride in their service and what the Corps stood for.

For many years, only former servicemen—including veterans of the RCMP who had served with distinction in several military conflicts including the Great War—could become Commissionaires. They were carefully screened to determine suitability. Commissionaires held responsible positions as aides-de-camp, receptionists, telephone operators, messengers, factory gatekeepers, checkers, night watchmen, while still others were employed on security work at private, federal and provincial installations. Commissionaires were also often available on short notice for temporary duties—a few hours or days—if needed.

Next Month: Part Two: Evolving the Corps to cope with modern challenges.