The Importance of trench papers in the Great War, Part 3

By Kyle Falcon

Life in the trenches was indescribably dirty and dangerous. Most of the time at the front was spent in muddy, cold wet trenches.. This delightful shot of a bather indicates that morale could be high at times, especially during periods of little gunfire. In the background, a fellow soldier is seen reading a trench newspaper. (Canadian War Museum, 19780093-0140)

On May 1, 1916, nearly an entire Canadian infantry battalion suddenly disappeared without a trace while resting in their billets. They would not be seen again until the next morning when they mysteriously reappeared during roll call. When probed about their whereabouts the day prior, the men could not explain what had happened to them. “Where had they been” the Listening Post probed?

One theory proposed a sinister explanation: “Was this the result of another German plot? Had the Huns … hypnotize[d] troops by hundreds?” This article was meant to be satirical. According to the writer, the soldiers, after receiving their pay that morning, had vanished when it was announced that all men were to report to their working party. Any soldier who read this piece would have gotten the joke rather quickly since “rest” behind the lines often involved hours of busy work meant to keep the troops active. Drills, parade, digging, and other physical labours were the subject of many complaints and jokes from the soldiers. In this same issue of the Listening Post, under the headline “Things we hear that don’t happen” was the quip: “The Division is going out for a rest.”

As mentioned in the previous article of this series, one response to the boredom and monotony that could accompany life in the trenches was to read and write. But troops also required a semblance of normalcy and fun. In addition to reading books, trench journals, and magazines, they played sports and attended concert parties. The popularity of football across the various theatres of the British war effort is hardly surprising given that a majority of the British divisions were composed of civilians. After hours of working in the trenches or behind the lines, it was only natural that the men would resort to playing sports when the opportunity arose, just as they did back home after a hard day’s work.

What is surprising is the extent of organized sport and the administrative and material support provided by officers and higher officials. Inter- and intra-battalion football, cricket, and baseball competitions were held to crowds of sometimes thousands. High command instructed officers to make sure the necessary supplies and space were allocated to the men. By June 1917, the 1st Canadian Division had nine baseball fields, three football fields, tennis courts, a basketball “court” and even two boxing platforms. Motor cars were also arranged to transport men to the big championship matches.

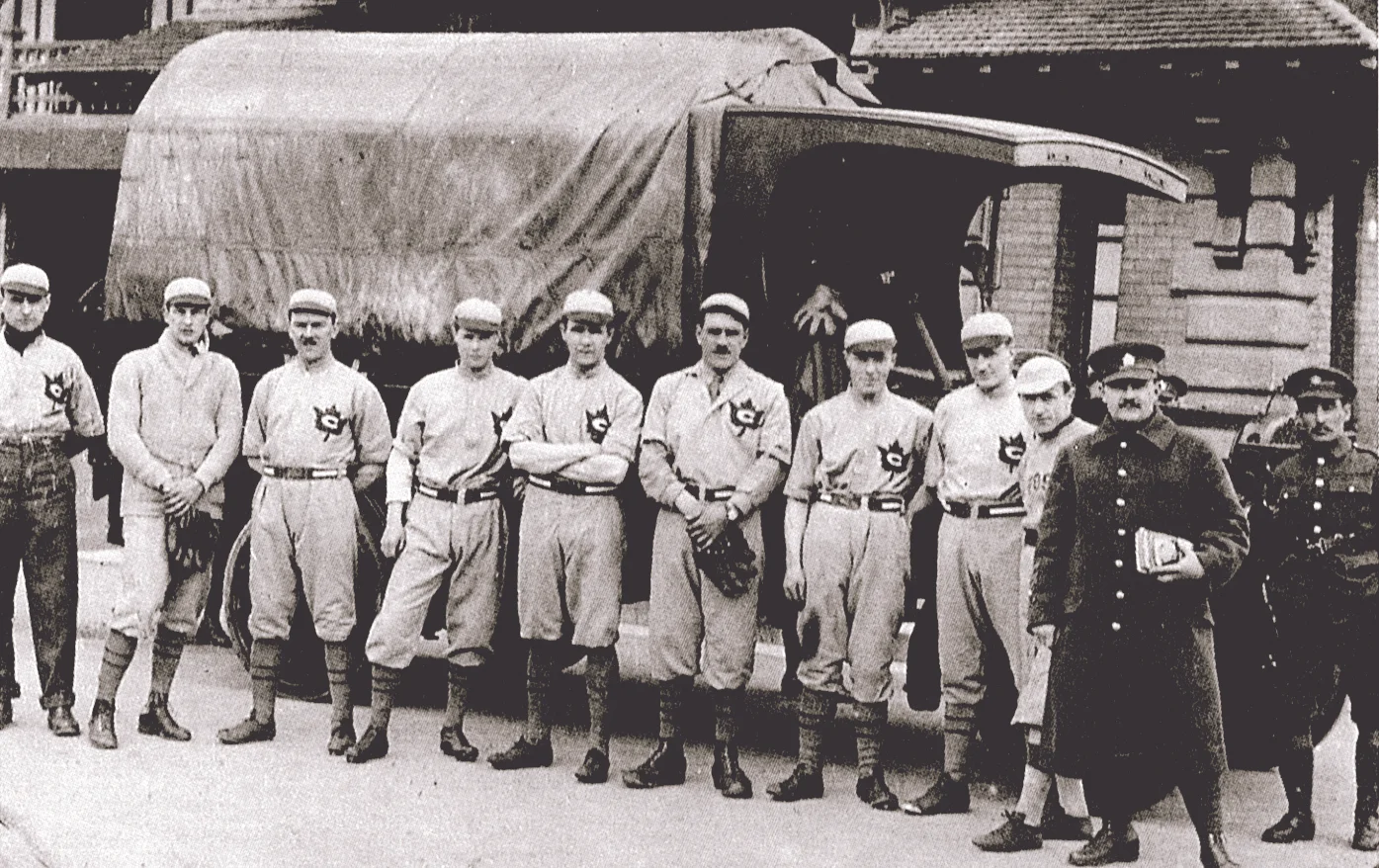

Sports were just as important at war as back home. To provide entertainment for the troops, matches were organized between teams and countries. Baseball teams played behind the lines and in Britain during the Great War, as did soccer teams. (Canadian War Museum, 19770477-011)

British and Dominion command increasingly recognized that organized sports could be beneficial for morale, physical exercise, and building camaraderie, especially between officers and their men. The No. 1 Canadian Field Ambulance for example was granted permission to put together an official football club in early 1916 by their commanding officers with a warrant officer, captain, and private serving as president, vice-president, and secretary respectively. This diffusion of rank represented to the Iodine Chronicle an example “of the democracy of sport” as well as official recognition by authorities that sport could be both good for the men’s physical fitness and spirit. As one writer commentated, “football [and] baseball … do more to keep Tommy fit and contented than all the route marches ever invented. Obviously, sports were preferable to drill, training, parade, trench work, and work parties.”

One did not have to directly participate in either concert parties or sporting events to be entertained by them. Those who could not play or attend could read accounts of the matches and concerts in the appropriate trench papers. The various motives of the trench press — to entertain, to build camaraderie, and to document a history of the battalion in France — made them an appropriate place for this lighter more “normal” side of service. These were often very detailed accounts that could transport the reader’s attention from the Western Front to the more homely and familiar theatres of games and music, as the following partial description of a Y.M.C.A. concert in the Listening Post demonstrates:

Hostilities commenced with a band selection — ‘Water, water everywhere but not a drink in sight.’ We knew it, in fact we could feel it from our knees downwards. Sgt. Clarke of the 10th Battalion then gave us a highly interesting 15 minutes whilst he argued the point with an imaginary German … through an imaginary telephone.

The next item was a comic song by our ever popular Sgt. Mc Vic. Needless … his song met with hearty applause …

The comic songs of Pte. O'Neill were the cause of a big sick parade next morning.

The next artiste, Drive Place of the R.C.H.A. gave us something new in the line of hand-cuff tricks …

Those of us who were strong enough to stand Pte. Skinners's version of ‘Where the River Shannon Flows’ had the choice of almost any seat in the house long before he had finished the first verse …

Private Lamont’s jokes and songs were just as welcome as they were the first time he sprung them on us (Last Fall) …

The last but not least turn of the evening was a demonstration of bloodless-surgery and hypnotism by Driver Place …

Thus what proved one of the best concerts ever held by the 7th Battalion came to a close by all heartily singing ‘God Save the King.’

These reports not only provide full details of the performances and performers but also worked in friendly jokes at others’ expense. With comments such as “was met with hearty applause,” it is also evident that the men genuinely enjoyed such productions and actively engaged in them as audience members.

Given that these summaries of games and concerts were so common, it is no wonder that the trench newspapers have proved to be valuable sources to understanding how soldiers coped and sustained morale. As historians have pointed out, the concert parties resembled in tone and production the music halls of the British and Dominion homelands. But the men did not perform in real coliseums or hippodromes or real baseball diamonds and football fields.

During the Great War, concert parties were encouraged by the commanding officers, as they provided a harmless outlet for soldiers in dealing with the hardships of life on the front line. These men of the 54th Battalion entertained their comrades and other units. (Canadian War Museum, 19790308-017)

Despite the transference in spirit and design of these cultural norms and aspects of civilized society, they were conducted in the shadow of war. During the aforementioned concert a power outage spread fears of a pending Zeppelin attack, sending some members of the audience into momentary hysteria. The reminder that one was at war being never far away. The content of the trench newspapers as a whole were a merging of the environment of the Great War with the culture of home and their goal was to make light of certain misfortunes, and attempt to live day-to-day in the trenches.