The Importance of trench papers in the Great War, Part 2

Hours of boredom, moments of terror: How trench papers allowed soldiers to share humour, break monotony and provide historical perspective

From November 2015 (Volume 22 Issue 10)

By Kyle Falcon

In the introduction to this series, I noted the significant scale of the trench press. Canadian, British, Australian, New Zealand, American, French and German troops all produced periodicals in various theatres of the Great War. Where did these publications come from and why did people contribute to them? This post will examine the various motivations that implored editors, contributors, and military staff to write for the Canadian trench papers.

In The Soldiers’ Press (2013), historian Graham Seal argues that the trench press emerged from a broader trench culture. Those who cohered to a trench community did so through a shared language, symbols, rituals, activities and, most importantly, a shared experience. The trench press was an expression of this culture and a forum for the men to communicate with the politicians, military authorities, the mainstream press, and those at home.

“The message was,” states Seal, “that the men of the trench would fight, no matter what, but on their own terms and in their own way, regardless of military traditions, hierarchies and authority, regardless of political incompetence and stupidity.” Articles of poetry, parody, satire, cartoons, and dark humour were part of this process of cultural expression and negotiation. But there was also another practical element of the war experience that the soldiers’ press was responding to: monotony.

It is no surprise that accounts of the great battles such as the Somme and Passchendaele reference mud, rats, death and maiming. But how representative is this of the broader experience?

If the average day of the Somme was typical of the entire four-year conflict, approximately four million of the six million British soldiers mobilized would have become a casualty, nearly twice the actual amount, and this is only one region of a front that spanned from the borders of Switzerland to the North Sea. If we were to take the approximately 40 kilometres of the Somme and extend its losses to the 700-kilometre-long Western Front, British casualties in the First World War would have neared 100 million. This does not include those serving in other theatres, the sea, or in the air.

To describe the war only through the devastating battles of attrition on the Western Front would omit a significant proportion of wartime experiences. A significant amount of time was also spent away from the front in reserve trenches, communication trenches, rest billets and leave. As Dan Todman states in The Great War: Myth and Memory, “the most frequently endured experience for most soldiers in combat arms was not terror or disgust but boredom.”

It is in this context that we can understand some of the more curious contents found within trench newspapers. On October 15, 1915, the No. 1 Canadian Field Ambulance’s first issue of The Iodine Chronicle reported the results of their moustache competition, with “Dope” Stewart winning first prize in the “Charlie Chaplin class.”

Although articles frequently criticized shirkers, politicians, and military leadership, the soldiers’ press was also responding to very basic needs. Soldiers desired entertainment and the writing and reading of soldiers’ periodicals could help contribute to this end. “War,” as the old adage aptly describes, “is hours of boredom punctuated by moments of terror.” Boredom and monotony were important but so were the moments of terror, as some periodicals emerged as an effort to record history. These elements help explain the range and popularity of the Canadian frontline press.

The inaugural edition of the 7th Canadian Infantry Battalion’s The Listening Post proclaimed, “I’m here to try and break trench monotony.” In their calls for contributions, the editors pointed out that the paper was designed to promote fun: “make [articles] as short as possible but long enough to get all the fun in.” A typical issue of The Listening Post contained eight pages and the format was designed to look like a regular newspaper. One could expect to find in any given issue articles, short stories, comics, news bulletins, and advertisements that transformed the monotony and horrors of war into satirical, light-natured pieces. In its first edition, The Listening Post contained the following advertisement:

Rooms to let … Dug. Inn. Guaranteed to be 50 feet below the surface. Near modern and Historic ruins. Owner left hurriedly on account of health. Long lease. Pumps or anything else which would not necessitate the reappearance of the owner would be installed free, as he is hoping to be absent for several years. Apply Sanitary Dept.

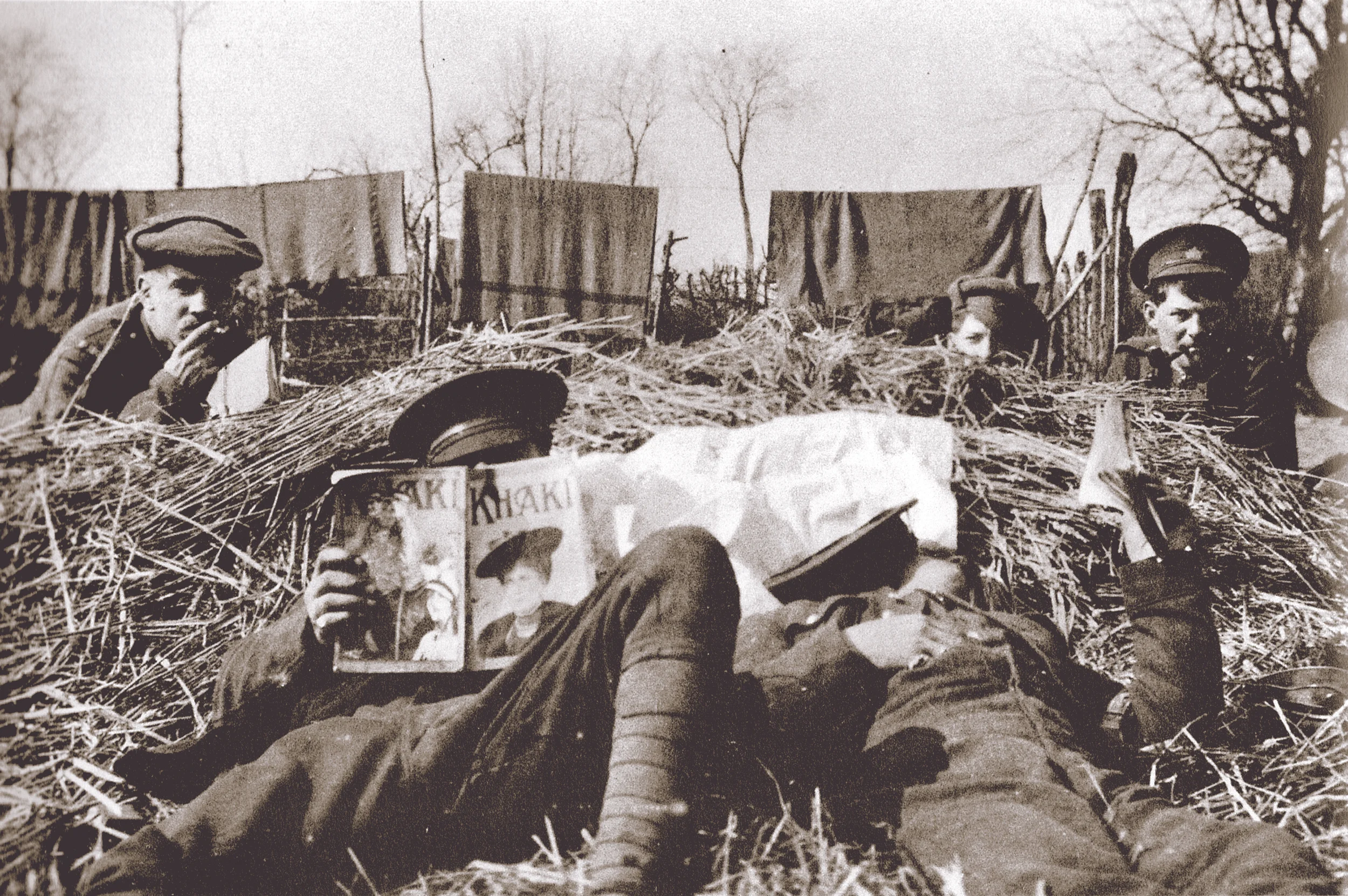

British officers outside a captured and well camouflaged German dressing station during the First World War. During quiet times, officers and enlist3ed men alike took advantage to write letters home, read trench newspapers, and smoke a pipe. (Imperial War Museum)

Other columns mixed humour with the trials and tribulations of trench life by highlighting their contradictions. A list of advice for “young Soldiers” in The Listening Post advertised: “When relieving a company in the firing line make as much noise as you can when going up the communication trench … If you are a sentry keep your head well above the parapet. Its safer.” This demonstrates the creative ways in which some soldiers found humour in their daily circumstances but also how quickly they could turn deadly. The duties were simple yet dangerous, clear yet contradictory. One was not to shout in a communication trench, or get a full view in a sentry post.

Trench newspapers found support among military authorities for similar reasons. In The Brazier, LCol. J. Edwards Leckie of the 16th Battalion sanctioned the paper “as a vehicle for regimental news and anecdote” through “verse, story, joke or sketch.”

There was also recognition that history was in the making, and trench newspapers could provide a means to record a unit’s historical voice. This was the professed hope of the 12th Canadian Field Ambulance paper, In & Out. The first issue was released in November 1918, and was justified by the editor as a way to record and preserve the voice of the unit before the war’s end. There was a strong demand to highlight the unit’s creative talent and provide a “memoir of our ‘mighty deeds’ for reference in later life.”

That the men who had fought in the war had experienced a history worth sharing was evident in the paper’s columns. One piece, “Survey and Forecast,” described the duties of the men and women of the 12th Field Ambulance as being “Stokers, plumbers, cooks and janitors, guards and prisoners … stretcher bearers and pack carriers, nurses and patients,” but no matter what transpired after the war, they “shall be … historians and story-tellers.”

German reserves stop to rest their horses and enjoy a meal. to deal with the emotions of being at war, some soldiers would write poems, humorous stories or serious articles for trench newspapers.

The first and only issue of In & Out proceeds to not only lighten the mood through verses of poems but also contains within it proud accounts of the duties of a medical corps. The monotonous work of erecting dressing stations and dugouts and dealing with the sick behind the lines were defended as crucial to the war effort. Writers also pointed out that men of the Field Ambulance were repeatedly exposed to enemy fire while they collected the wounded. Whether writing about monotony or danger in humorous or serious prose, the articles in In & Out were determined to record the stories and experiences of these men and women.

The importance of the monotony of trench life should not be underscored in any narrative of the trench papers. The Canadian frontline press offered a means to break trench monotony through both reading and writing. Some soldiers chose to make light of their circumstance or write poetry to simply pass the time, others to record their voice for the historical record.